After months of assurances from the Johnson administration, and with nearly a half-million U.S. troops in country, the American public had good reason to believe that January 1968 would mark the beginning of the end of the conflict. By summer, that belief would be seriously shaken — with major political and social consequences at home.

Overview

On January 21 at Khe Sanh, 30,000 North Vietnamese troops attacked an air base held by just 6,000 United States Marines. The attack on Khe Sanh, however, proved to be a diversionary tactic for the larger Tet Offensive.

January 30 marked the first day of the Vietnamese lunar new year celebration, called Tet. Just days before, as the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) prepared to observe the holiday with a truce, some 84,000 North Vietnamese Army (NVA)and Viet Cong (VC) troops prepared coordinated attacks on 36 provincial capitals in South Vietnam, along with dozens of U.S. and ARVN military bases and large cities including Huế, Da Nang, and Saigon.

The north launched near simultaneous attacks on more than 100 South Vietnamese and American military locations. January 31 proved to be the bloodiest day of the entire war for the Americans, losing 246 people.

Militarily, the Tet Offensive was an abject failure for the north — NVA and VC forces suffered massive casualties and failed to hold any gains they had made. Perhaps more importantly, the people of South Vietnam were not inspired to rise up against their government and U.S. forces, as had been the hope of the offensive’s architect, Ho Chi Minh.

Politically, however, Tet was a turning point in the war.

Having been assured that the enemy was both demoralized and incapable of mounting a major offensive, the American public was sobered by nightly images of vicious combat and a mounting U.S. body count — including more than 2,400 troops killed in May 1968, the bloodiest month of the conflict. In February, news anchorman Walter Cronkite announced that it seemed “more certain than ever that the bloody experience of Vietnam is to end in a stalemate.”

As public support for President Johnson’s handing of the war fell to record lows, Johnson recalled General William Westmoreland to Washington, replacing him with General Creighton Abrams, but it was too late. Facing primary challenges from emboldened candidates within his own party, the President announced that he would neither seek nor accept the Democratic nomination for reelection. While Tet Offensive failed to achieve North Vietnam’s military goals, it had inadvertently succeeded in turning the tide of American public sentiment, signaling the beginning of the end of Johnson’s presidency.

Casualties

Go to Panel 35 E. Half of the panels on The Wall include names of those who died in 1968, the deadliest year of the Vietnam War. Among the major engagements of that year, the siege of Khe Sanh, the battle of Hue, and the Tet Offensive were among the bloodiest of the war.

Beginning on January 30, 1968, the Tet Offensive consisted of surprise attacks by the North Vietnamese against more than 100 military and civilian control centers all over South Vietnam. The campaign launched on the Tet new year holiday. While the fighting would continue for months, the United States would lose 246 service members on January 31 alone, making it the bloodiest day of the war. The deaths from just that day stretch from Panel 35 East, Line 84 to Panel 36 East, Line 44 on The Wall.

The first name listed under that day is Corporal Ghalib A. Abdullah on Panel 35 East, Line 84. During the Tet Offensive assault on Can Tho Army Airfield, Abdullah was defending the perimeter fence when he was killed by enemy fire. Ghalib was from Brooklyn and a 1960 graduate of the School of Industrial Arts in New York City.

Medal of Honor

Beginning on January 30, 1968, the Tet Offensive consisted of surprise attacks by the North Vietnamese against more than 100 military and civilian control centers all over South Vietnam. The Tet Offensive began with the invasion and occupation of Hue City and would last through March. US Marines spent nearly a month engaged in a brutal battle to retake the city.

The chaotic battle saw unprecedented heroism – and resulted in five Medals of Honor. Read the stories of two Medal of Honor recipients below.

Alfredo Gonzalez was 21 years old when his heroic actions on February 4, 1968 posthumously earned him the Medal of Honor.

Gonzalez was born May 23, 1946, in Edinburg, Texas. He graduated from Lamar Grammar School in 1955, and from Edinburg High School in 1965. Gonzalez later enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps. He completed recruit training with the 3d Recruit Training Battalion, Marine Corps Recruit Depot, San Diego, California, the following September, and individual combat training with the 2d Battalion, 2d Infantry Training Regiment, Marine Corps Base, Camp Pendleton, California, that October.

After completing individual combat training, he became a rifleman with Headquarters and Service Company, 1st Reconnaissance Battalion, 1st Marine Division, and served in that capacity until January 1966. He next saw a one year tour of duty as a rifleman and squadron leader with Company L, 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, 3d Marine Division. He was promoted to private first class In January of 1966; to lance corporal in October of that year, and then to Corporal in December of 1966.

Upon his return to the United States in February 1967, he saw duty as a rifleman with the 2d Battalion, 6th Marines, 2d Marine Division, Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. Ordered to the West Coast in May 1967, he joined the 3d Replacement Company, Staging Battalion, Marine Corps Base, Camp Pendleton, California, for transfer to the Far East.

In July of 1967, he was promoted to sergeant, and later that month, arrived in the Republic of Vietnam. He served as a squad leader and platoon sergeant with the 3d Platoon, Company A, 1st Battalion, 1st Marines, 1st Marine Division.

While participating in the initial phase of Operation Hue City in the vicinity of Thua Thien, Vietnam, on February 4, 1968, Sergeant Gonzalez was mortally wounded from hostile rocket fire.

Citation: For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while serving as platoon commander, 3d Platoon, Company A. On 31 January 1968, during the initial phase of Operation Hue City, Sgt. Gonzalez’ unit was formed as a reaction force and deployed to Hue to relieve the pressure on the beleaguered city. While moving by truck convoy along Route No. 1, near the village of Lang Van Lrong, the marines received a heavy volume of enemy fire. Sgt. Gonzalez aggressively maneuvered the marines in his platoon, and directed their fire until the area was cleared of snipers. Immediately after crossing a river south of Hue, the column was again hit by intense enemy fire. One of the marines on top of a tank was wounded and fell to the ground in an exposed position. With complete disregard for his safety, Sgt. Gonzalez ran through the fire-swept area to the assistance of his injured comrade. He lifted him up and though receiving fragmentation wounds during the rescue, he carried the wounded marine to a covered position for treatment. Due to the increased volume and accuracy of enemy fire from a fortified machine gun bunker on the side of the road, the company was temporarily halted. Realizing the gravity of the situation, Sgt. Gonzalez exposed himself to the enemy fire and moved his platoon along the east side of a bordering rice paddy to a dike directly across from the bunker. Though fully aware of the danger involved, he moved to the fire-swept road and destroyed the hostile position with hand grenades. Although seriously wounded again on 3 February, he steadfastly refused medical treatment and continued to supervise his men and lead the attack. On 4 February, the enemy had again pinned the company down, inflicting heavy casualties with automatic weapons and rocket fire. Sgt. Gonzalez, utilizing a number of light antitank assault weapons, fearlessly moved from position to position firing numerous rounds at the heavily fortified enemy emplacements. He successfully knocked out a rocket position and suppressed much of the enemy fire before falling mortally wounded. The heroism, courage, and dynamic leadership displayed by Sgt. Gonzalez reflected great credit upon himself and the Marine Corps, and were in keeping with the highest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.

Vice President Spiro T. Agnew presented the Medal of Honor to Gonzalez’s mother on October 31, 1969.

The name of Alfredo Gonzalez is remembered on Panel 37E, Line 21 of The Wall.

Clifford Chester Sims was 25 years old when he made the ultimate sacrifice on February 21, 1968. For his actions, he was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

Sims enlisted in the U.S. Army in September 1961 after graduating from high school. Sims completed his basic training at Fort Jackson, South Carolina and then attended Airborne School at Fort Benning, Georgia before being sent to the 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg. In August 1967, Sims moved to Fort Campbell, Kentucky to join Company D, 2nd Battalion (Airborne), 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division and from there – was sent to Vietnam. He held the rank of Staff Sergeant.

On February 21, 1968, Sims and his squad were approaching a bunker when they heard the unmistakable noise of a concealed booby trap being triggered immediately to their front. Sims warned his comrades then hurled himself upon the device as it exploded, taking the full impact of the blast. He sacrificed his life to save members of his squad.

Citation: For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty. S/Sgt. Sims distinguished himself while serving as a squad leader with Company D. Company D was assaulting a heavily fortified enemy position concealed within a dense wooded area when it encountered strong enemy defensive fire. Once within the woodline, S/Sgt. Sims led his squad in a furious attack against an enemy force which had pinned down the 1st Platoon and threatened to overrun it. His skillful leadership provided the platoon with freedom of movement and enabled it to regain the initiative. S/Sgt. Sims was then ordered to move his squad to a position where he could provide covering fire for the company command group and to link up with the 3rd Platoon, which was under heavy enemy pressure. After moving no more than 30 meters S/Sgt. Sims noticed that a brick structure in which ammunition was stocked was on fire. Realizing the danger, S/Sgt. Sims took immediate action to move his squad from this position. Though in the process of leaving the area 2 members of his squad were injured by the subsequent explosion of the ammunition, S/Sgt. Sims’ prompt actions undoubtedly prevented more serious casualties from occurring. While continuing through the dense woods amidst heavy enemy fire, S/Sgt. Sims and his squad were approaching a bunker when they heard the unmistakable noise of a concealed booby trap being triggered immediately to their front. S/Sgt. Sims warned his comrades of the danger and unhesitatingly hurled himself upon the device as it exploded, taking the full impact of the blast. In so protecting his fellow soldiers, he willingly sacrificed his life. S/Sgt. Sims’ extraordinary heroism at the cost of his life is in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflects great credit upon himself and the U.S. Army.

Sims is buried at Barrancas National Cemetery in Pensacola, Florida. His name is remembered on Panel 40E, Line 56 of The Wall.

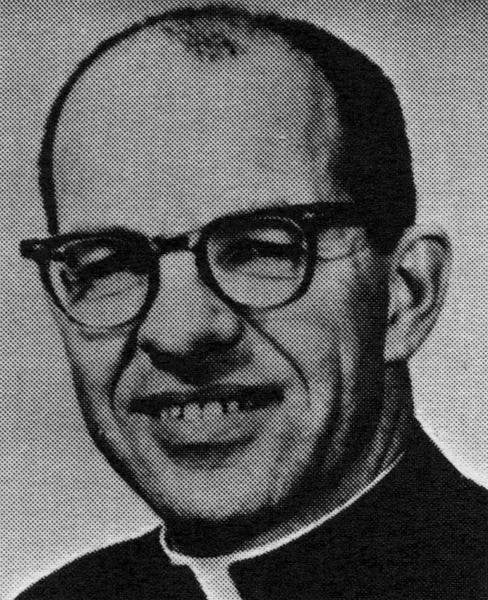

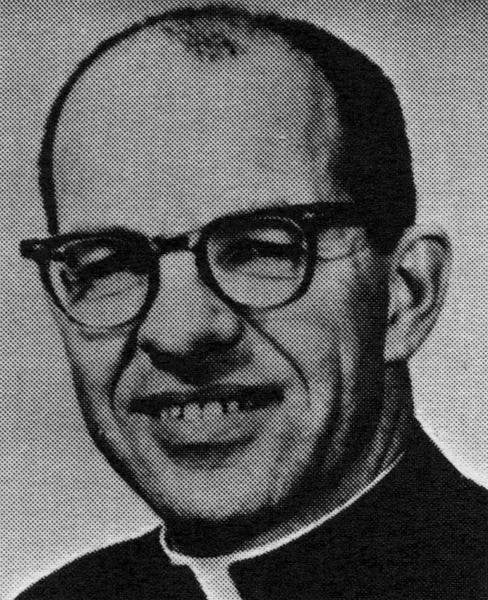

On February 17, 1968, Army Chaplain Aloysius McGonigal joined the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines in the final assault on the Citadel in Hue. While administering comfort and last rites, he was killed by small arms fire. McGonigal was a former physics teacher from Washington, D.C. He was serving the Roman Catholic Church. His name is remembered on Panel 39E, Line 75 of The Wall.

McGonigal is one of 16 chaplains with names inscribed on The Wall.

This segment from Iowa Public Television’s Iowans Remember Vietnam includes archival footage and interviews with Iowa veteran Paul Dwyer. Dwyer describes his role as a radio operator during the war, and explains his experiences during the Tet offensive.

Charles Sudholt, a U.S. Marine Veteran, shares his experience on the day that the Tet Offensive was launched.

The Media

Americans’ opinions about the war were shaped not just by news reports and photographs but also by editorials. While many media remained supportive of the war, some major news organizations became increasingly critical as time passed.

After senior military leaders and the President of the United States told the American public that the enemy was all but defeated and could not launch a major operation, Americans watched the news footage that showed just the opposite.

In February 1968, CBS News aired on television a special report on the aftermath of the Tet Offensive. At the end of the report, renowned anchorman Walter Cronkite read a brief editorial suggesting that the United States was mired in a stalemate.

It is claimed that after President Johnson watched the report, he said “If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost middle America.” In March of 1968, Johnson announced that he would not seek reelection.

EP21 – The Tet Offensive

On January 30, 1968, North Vietnamese and Viet Cong troops launched an offensive that is widely considered a pivotal moment in the war. Vietnam War specialist Dr. Erik Villard sheds a historian’s light on the Tet Offensive.

EPISODE SHOW NOTES

- Dr. Erik Villard book Staying the Course – https://history.army.mil/html/books/091/91-15-1/index.html

- VVMF Topic page Tet Offensive – https://www.vvmf.org/topics/Tet-Offensive/

- VVMF Reading of the Names – vvmf.org/ROTN

- VVMF The Wall That Heals – vvmf.org/the-wall-that-heals

- VVMF Legacy Challenge – vvmf.org/legacy

- Don Oberdorfer book Tet! The Turning Point in the Vietnam War – https://www.amazon.com/Tet-Turning-Point-Vietnam-War/dp/0801867037

- YouTube Echoes of the Vietnam War Interview playlist – https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLK63b6Cn53unMMj-yZYEch0RuYy1YN1zl

EP45 – Joe Zengerle

December of 1967 was a pivotal time to arrive in Vietnam. A month later, the Tet Offensive would alter the course of the war, public sentiment about its prosecution, and the direction of a presidency. From his unique vantage point as General William Westmoreland’s special assistant, Joe Zengerle saw the world transform itself in the first half of 1968.

Additional Resources

The Tet Offensive

- What happened in the Tet Offensive’s first 36 hours [Military Times]

- VIDEO: “Things Fall Apart” – Episode 6 of The Vietnam War: A Film by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick [pbs.org]

- Military Victory But Political Defeat: The Tet Offensive 50 Years Later [NPR]

- “Tet Offensive” [History.com]

- The Tet Offensive: The Battle for Vietnam’s Cities [Magnum Photos]

American Media and Public Sentiment

- Tet Offensive: a turning point for war and public opinion [Stars & Stripes]

- VIDEO: Walter Cronkite announcement about the Vietnam War

- “How the Tet Offensive Undermined American Faith in Government” [The Atlantic]

- VIDEO: “Did the news media, led by Walter Cronkite, lose the war in Vietnam?”

[Washington Post] - VIDEO: “Remembering 1968: The Tet Offensive” [CBS News]

Khe Sanh

- VIDEO: “Under Siege at Khe Sanh” [ABC News]

- “Khe Sanh” [History.com]

- The Battle of Khe Sanh and Its Retellings

Huế

- VIDEO: “Marine Corps Battles: Hue City” [Military.com]

- “Americans remember grinding, exhausting Hue battle as ‘particularly brutal’”

[Stars & Stripes]

Da Nang

Saigon

- VIDEO: Tet Offensive 1968, US Embassy Saigon fighting

- Viet Cong attack U.S. Embassy [History.com]