The Inspiration

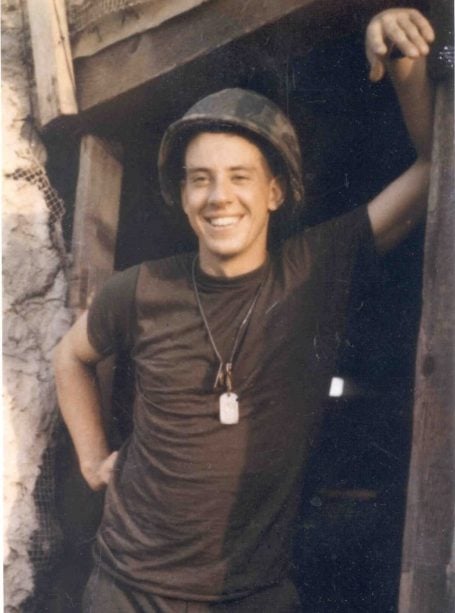

On January 21, 1970, Jan Scruggs was having his morning cup of coffee, but he was far from his kitchen table at home. He was in Vietnam, serving in the 199th Light Infantry Brigade.

In the nine months since he’d been in-country, Scruggs had already seen a lot of action and had been wounded in a battle near Xuan Loc. He had spent three months recovering in a hospital before being sent back to fight with rocket-propelled grenade fragments permanently embedded in his body.

On that January day, “There was a big explosion,” Scruggs recalled. “I ran over to see a truck on fire and a dozen of my friends dying.” They had been unloading an ammunition truck when the explosion occurred. Scruggs would never forget the awful scene. He would never forget those friends.

In fact, he would spend a lifetime trying to honor their memory.

The Vision

Scruggs was raised in a rural Maryland town between Baltimore and Washington, D.C. His mother was a waitress; his father a milkman. “We’re all the result of our upbringing. My background was relatively modest,” he said. “But I was always impressed with the example my parents set.”

When the 18-year-old Scruggs volunteered to enlist in the Army in 1968, debate surrounding Vietnam was escalating. The war’s length and the growing number of casualties were fueling tensions. Within months after he recovered from his wounds and returned to his unit, the American public was learning the details of the events at My Lai. By the time he returned home, three months after the explosion, the country was even further divided.

Over the next few years, as the war came to a close and more and more troops returned home, the media began to paint a picture of the stereotypical Vietnam veteran: drug addicted, bitter, discontented, and unable to adjust to life back home. Like all stereotypes, this one was unfair.

The truth was, veterans were no more likely to be addicted to drugs than those who did not serve. And if they were bitter, who could blame them? When they returned home from serving their country, there was no national show of gratitude. They were either ignored or shouted at and called vicious names. Veterans frequently found themselves denying their time in Vietnam, never mentioning their service to new friends and acquaintances for fear of the reactions it might elicit.

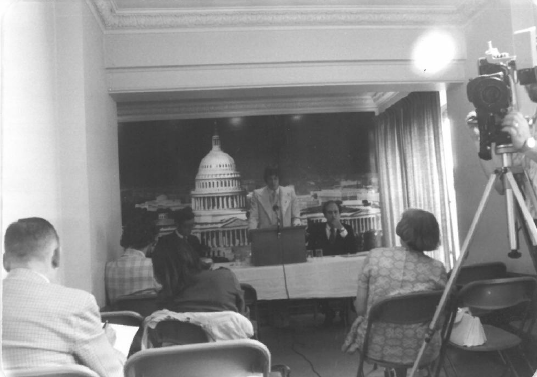

By June 1977, Scruggs was attending graduate school at American University in Washington, D.C. and had embarked on a research study exploring the social and psychological consequences of Vietnam military duties. He found that returning veterans were finding it hard to trust people. They were feeling alienated from the nation’s leaders, and they had low self-esteem. He also found that those veterans whose units experienced high casualty rates were experiencing higher divorce rates and a greater frequency of combat-related dreams. Using his findings, he testified at the Senate hearing on the Veteran’s Health Care Amendments Act of 1977, with the hope that he could help veterans gain access to the services and support they needed.

He also wanted to find a way to help them heal and suggested that the country build a national memorial as a symbol that the country cared about them.

By 1979, the country was beginning to have more positive feelings toward Vietnam veterans. Movies were dealing more realistically with their issues. And Congress had declared a “Vietnam Veterans Week” for that April to honor those who had returned home.

One film that came out early that year, The Deer Hunter, explored the effects of war on three friends, their families and a tight-knit community. When Scruggs went to see the movie in early 1979, it wasn’t the graphic war scenes that haunted him. It was the reminder that the men who died in Vietnam all had faces and names, as well as friends and families who loved them dearly. He could still picture the faces of his 12 buddies, but the passing years were making it harder and harder to remember their names.

That bothered him. It seemed unconscionable that he–or anyone else–should be allowed to forget. For weeks, he obsessed about the idea of building a memorial.

“It just resonated,” he explained. “If all of the names could be in one place, these names would have great power—a power to heal. It would have power for individual veterans, but collectively, they would have even greater power to show the enormity of the sacrifices that were made.”

His research had proven that post-traumatic stress was real and had shone a light on the challenges faced by a significant number of military veterans. The idea for a memorial seemed like a natural extension of his work and his growing desire to find a way to help veterans. He had studied the work of psychiatrist Carl Jung, a student of Sigmund Freud, who wrote of shared societal values. As Scruggs analyzed the concept of collective psychological states, he realized that, just as veterans needed psychological healing, so too did the nation.

“The Memorial had several purposes,” he explained. “It would help veterans heal. Its mere existence would be societal recognition that their sacrifices were honorable rather than dishonorable. Veterans needed this, and so did the nation. Our country needed something symbolic to help heal our wounds.”

Building Support

Once Scruggs decided to build the memorial, the next step was to get some people behind him. An ad hoc group of veterans had scheduled a meeting to try to use Vietnam Veterans Week to generate publicity for veterans’ need, and Scruggs thought that would be a good time to announce his plans.

But instead of enthusiasm, he received skepticism. Most at the meeting told him they didn’t want a memorial; they wanted more benefits and government support. But the meeting gave Scruggs his first ally: former Air Force intelligence officer and attorney Robert Doubek, who thought a memorial was a good idea.

“When I was attending law school, Vietnam veterans were an anomaly among the young single professional set of Washington, so it was something you didn’t mention.” remembered Doubek. “It seemed unfair and inappropriate that there should be no recognition.”

Doubek approached Scruggs after the meeting and suggested that he form a nonprofit corporation as a vehicle to build a memorial. On April 27, 1979, Doubek incorporated the fledgling entity, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, and Scruggs asked him to be an officer and director.

To make his dream a reality, he planned to get support from people as diverse as former anti-war presidential candidate George McGovern and Gen. William Westmoreland, who commanded U.S. forces in Vietnam. Scruggs took two weeks off from his job at the Department of Labor to develop the idea further.

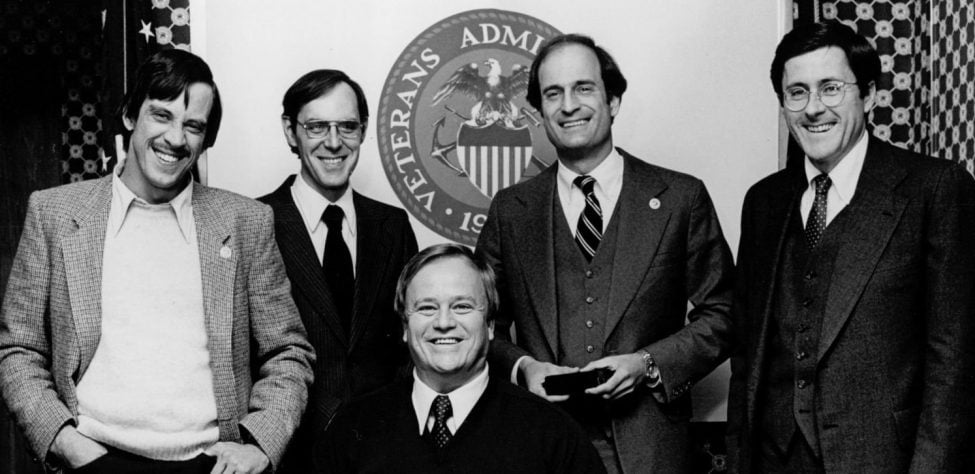

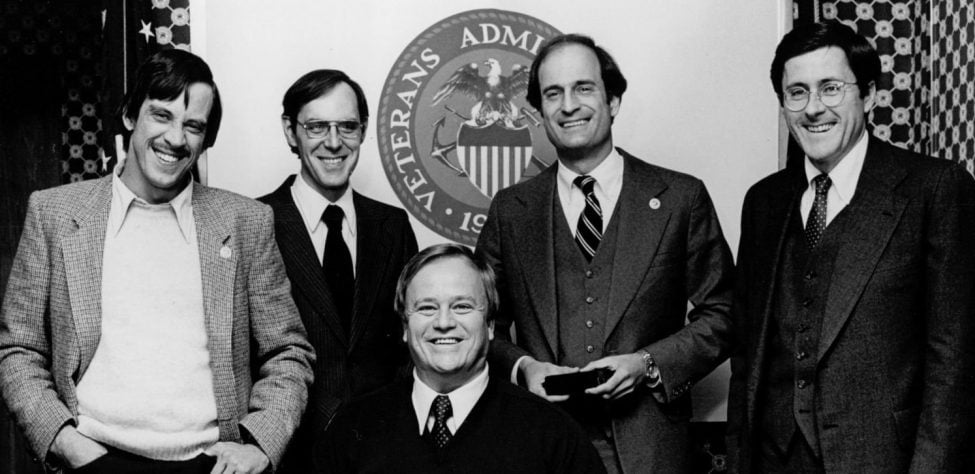

Scruggs and Doubek began having regular meetings with John P. Wheeler, a graduate of West Point and Harvard Business School. Wheeler recruited others to help, starting with a group of professional men, all Vietnam or Vietnam-era veterans: George “Sandy” Mayo, Arthur Mosley, John Morrison, Paul Haaga, Bill Marr, John Woods and certified public accountant Bob Frank, who agreed to become VVMF’s treasurer. Paul Haaga’s spouse, Heather Sturt Haaga, soon came forward to lend her experience in fund raising. William Jayne, who had been wounded in Vietnam, volunteered to head up public relations activities.

The greatest challenge VVMF faced, said Doubek, was “to put together a functioning organization with people who didn’t know one another, people who were very young and didn’t have a lot of experience. We had to constantly find the most effective next step to take and be sure not to get waylaid by tangents.” The group started to hold regular planning meetings

For Woods, the growing coalition was a prime example of “it’s not what you know, it’s who you know.” These people, though a small group, were able to reach out to their networks and their extensive contacts to recruit the type of expertise and support required for such a mammoth initiative. Their military experience meant they had contacts far and wide, at all levels of all professions, within government and the private sector. It seemed every time they contacted someone, they were greeted with enthusiasm for the idea. Everyone wanted to join the effort. And if they themselves didn’t know how to help, they knew someone who did.

Their initial timeline was aggressive, with an ultimate goal of dedicating the Memorial on Veterans Day 1982—just a little more than 36 months away. The list of tasks to achieve such a goal seemed endless. They needed to secure a plot of land, raise funds and public awareness, design the Memorial, coordinate construction, and organize the dedication ceremonies. Most importantly, they needed to navigate the channels of government authorizations and approvals.

Never in the history of the United States had a national memorial been conceived, approved, built and dedicated in that short an amount of time. But if the challenges seemed insurmountable, no one expressed any fears. And none of them discussed their own personal feelings or political views regarding the war. All of them realized how critical it was that a memorial be apolitical. They set their sights in support of the clear, simple vision Scruggs outlined: to honor the warrior and not the war.

The Congressional Mandate

The VVMF organizers soon learned that it required an Act of Congress to build a memorial on Federal land, and Scruggs first called one of the senators for his home state of Maryland. Charles “Mac” Mathias, a Navy veteran of World War II, had been opposed to the war in Vietnam, but he had always respected those who served in it.

Mathias set up a meeting so he could learn more. “I had my ear to the ground,” Mathias recalled. “I heard there was a group of serious veterans, not just people getting together to have a beer in the evening, but a group that was serious about getting together to address the problems of the veterans.”

Mathias had grown increasingly concerned about how veterans had been treated on their return. Because he possessed great knowledge of history, he understood the extensive healing process required after war. A memorial made perfect sense to him. It would be a way to honor the veterans and to help them—and the country—heal.

“Initially the (Senator’s) staff was split,” recalled Monica Healy, a long-time Mathias aide, “on whether Mathias should take the lead and support the efforts to build the Memorial. The senior staffers were against it. It was the Senator’s gut feeling that we needed to do this.”

“This was serious business,” Mathias said. “You had to live through that period to really understand it. . . But the veterans had real problems. They needed support, friendship and help. And that message got through to me.”

Mathias also knew the country was ready, Healy recalled. Timing is everything, and enough time had passed. Intellectually and emotionally, America could embrace the idea.

Scruggs and Doubek met with Mathias to outline their plans. They stressed that all funds for the Memorial would be raised from private donations. No government funds would be necessary. What they did need, however, was an acceptable location for the Memorial and enough support to push the idea through various governmental committees and agencies.

The site and the legislation

One of Mathias’ early key suggestions was that the memorial should be on the Mall, especially because the anti-war demonstrations had taken place there. Wheeler had the idea to bypass the traditional site selection route and have Congress pass legislation to award a specific area for a memorial site. Scruggs, Wheeler, and Doubek then scouted the Mall – sometimes by bicycle – to identify the ideal spot: a stretch of parkland known as Constitution Gardens, located on the National Mall adjacent to the Lincoln Memorial.

Among other duties, Healy was the member of Mathias’ staff who handled memorials and worked as the liaison with the U.S. Department of the Interior. Because of this, Mathias appointed her to manage the details and to work with Scruggs, Doubek, and Wheeler on the legislation for the memorial. “The three of them had different strengths,” Healy explained. “Jan was a great spokesperson. Bob was the detail person and a good writer. Jack was the visionary, the creative, big-picture guy. They really worked well together and were the driving force. It was such a great cause, and they were bound and determined to make it happen.”

Enlisting Senator John Warner

As they forged a partnership with Mathias and his staff, VVMF also set out to establish other key relationships. Scruggs took a bold step in contacting Virginia Senator John Warner. Warner, who had served as Secretary of the Navy during the war, was himself a veteran of World War II and the Korean War. After meeting with the VVMF officers and advisors, Warner volunteered to help the organization raise the seed money needed to launch the fund raising campaign.

Because Warner was from Virginia and Mathias from Maryland, the two had worked together on many regional issues. “We had been friends for a long time,” Mathias said. “He was an excellent partner and fundraiser.” Mathias knew the legislative process. Warner, at the time married to Elizabeth Taylor, had strong connections to both Hollywood and the corporate world.

On November 8, 1979, VVMF held a press conference in which Mathias, Warner, and several others announced the introduction of legislation to grant two acres of land near the Lincoln Memorial for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

With the introduction of legislation, the VVMF leaders realized that it was time to transition from a volunteer committee and to open a staffed office. In December Doubek became the Executive Director, working on a half-time basis for the first few months, and opened the VVMF office on January 2, 1980. He organized the advisors and volunteers into task groups: public relations, financial management, fund raising, legislation, site selection, and design/construction. The priorities were to launch fund raising and achieve passage of the authorizing legislation.

The task groups proved effective, as described by John Woods, who jointed as a key advisor. He cited the growing coalition was a prime example of “it’s not what you know, it’s who you know.” These people, though a small group, were able to reach out to their networks and their extensive contacts to recruit the type of expertise and support required for such a mammoth initiative. Their military experience meant they had contacts far and wide, at all levels of all professions, within government and the private sector. It seemed every time they contacted someone, they were greeted with enthusiasm for the idea. Everyone wanted to join the effort. And if they themselves didn’t know how to help, they knew someone who did.

After working alone for six months, Doubek was joined on the staff by Kathy Kielich, who served as the Office Manager throughout the project.

Teaming up with the families

Early in his efforts Scruggs had called on Emogene Cupp, then the national president of the American Gold Star Mothers. “Jan came to our headquarters to see if we had any room to help them get started,” Cupp remembered. “We didn’t have any space, but I liked their idea and told them I would volunteer to help with all that I could.”

The Gold Star Mothers is a group of mothers whose sons or daughters have died serving their country. Their motto is: “Honor the dead by serving the living.” Volunteering to assist VVMF was an ideal opportunity for Cupp to do just that.

Cupp had experienced firsthand the pains caused by the war. Her only son Robert, an Army draftee, was killed by a land mine on his 21st birthday, June 6, 1968. Compounding the pain was that society’s ill treatment of the veterans extended to their families. “It was very hurtful,” Cupp recalled. “They treated the moms the same as they treated the vets. They weren’t nice. At that time, they just ignored you and wished you would go away. Or, people would tell me, ‘Well why did you let him go?’ Of course, what choice do you have?”

Scruggs and Doubek realized that Cupp could be instrumental in helping communicate the all-important personal, emotional side of the healing story. Cupp attended many of their meetings on Capitol Hill as they drummed up support.

Funding the Effort

Just before Christmas 1979, Warner hosted a fundraising breakfast in his Georgetown home. He made an impassioned plea for funding to his guests, members of the defense industry. Before he spoke, however, all eyes had turned toward the kitchen door, from which has emerged his then-wife, actress Elizabeth Taylor. She greeted each visitor in a regal fashion, wearing a dressing gown, perfect makeup, and beautiful shoes that curled up at the toes. “I’m sure I looked like a deer in the headlights, I was so nervous,” Scruggs recalled. “I think I even spilled my coffee.” But, her presence made a difference. “I heard that those present agreed to double their contributions after Taylor completed her remarks,” Scruggs said.

With the seed money from several defense industry donors, especially Grumman Aerospace, VVMF launched its first large-scale direct mail campaign to reach out to the public. To created credibility for the fledgling effort, they formed the National Sponsoring Committee, which included then-first lady Rosalynn Carter, former President Gerald Ford, Bob Hope, future first lady Nancy Reagan, Gen. William C. Westmoreland, USA, Vietnam veteran author James Webb, and Adm. James J. Stockdale, USN.

The first fundraising letter was signed by Bob Hope. It echoed the theme that regardless of how anyone felt about the war itself, everyone cared about honoring the men and women who had served and those who had ultimately lost their lives.

By early 1980, contributions started to arrive. Millionaire H. Ross Perot made a sizeable donation.

Direct mail was proving to be a highly effective fundraising tool. Letters came from moms, dads, grandparents, sons and daughters with heartfelt notes accompanied by checks and dollar bills. They came from veterans and from the neighbors, teachers, coaches and friends of veterans. The public wanted to have a hand in helping to build the Memorial and in honoring the warrior, not the war.

As VVMF focused on fundraising, Sens. Mathias and Warner continued to rally support and ferry the legislation. Mathias and Warner continually stressed that their objective was to provide the country with a symbol for reconciliation.

“There were so many people helping to get the legislation [passed],” remembered Healy. “The more people you got to co-sponsor, the more people wanted to join.”

On April 30, 1980, the Senate approved legislation authorizing the Memorial, followed by approval in the House on May 20, 1980. Although differences in the two bills required a Conference Committee to meet, on July 1, at a White House Rose Garden ceremony, President Jimmy Carter signed legislation providing two acres for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on the National Mall.

With the site approved, VVMF scrambled to address the issues of what the Memorial would look like and who would design it. A few preliminary concepts were embraced. As Scruggs had always envisioned, the Memorial would feature all of the names of those who had died. Wheeler suggested that it should be a landscaped solution: a peaceful, park-like setting that could exist harmoniously with the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial.

They were also keenly aware that the legislation made the Memorial’s design subject to the approval of the Commission of Fine Arts (CFA), the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC), and the Secretary of the Interior.

It was decided that VVMF would hold a design competition, open to any American citizen over 18 years of age. Just as the American people could be a part of building the Memorial through their contributions and support, they could also have an opportunity to participate in its design.

As a first step, VVMF retained architect Paul Spreiregen to serve as the Professional Advisor for the competition. Spreiregen, a graduate of the MIT School of Architecture and Planning, was a Fulbright Scholar who had served as the director of urban design programs at the American Institute of Architects (AIA) from 1962-66 and as the first director of architecture programs at the National Endowment for the Arts from 1966-70. An author, teacher, and lecturer, Spreiregen had written the authoritative book on design competitions.

At the time, well-managed open design competitions were common in Europe, but not in the United States. Most, like the Lincoln Memorial, were competitions between select designers. Only a few, such as the St. Louis Gateway Arch, part of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, had been the result of open competitions.

Spreiregen wrote, “I saw this as a needed opportunity to honor the service and lives of the soldiers we had lost and do so by running a model competition.”

Arthur Mosley headed the site selection task group and was assisted by John Woods, a structural engineer, who had been permanently disabled in a helicopter crash in Vietnam. (Woods continues to serve on VVMF’s Board of Directors to this day.)

For three solid months, Spreiregen, Mosley, Woods, and Doubek planned the competition. “We had to build credibility among the design community, but also build credibility with the veterans,” said Woods. “The design competition also needed to be able to attract design competitors.”

There were four phases to the design competition spanning almost one year: planning and preparation; the launch; the design phase; the design evaluation and selection; the press conference and public presentation. The selected design then had to go through Federal agency approval and development into finished plans.

“The first phase encompassed the detail planning and preparations for holding the competition,” said Spreiregen. “Holding a competition is like launching a rocket. Everything has to be thought out and in place before the launch button is pressed.”

The design criteria

The purpose of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was to honor all who had served, with a special tribute – their names engraved – for those who did not return. The chief design criteria were that the memorial be 1) reflective and contemplative in character; 2) be harmonious with its site and environment, 3) make no political statement about the war itself, and 4) contain the names of all who died or remained missing. “The hope is that the creation of the Memorial will begin a healing process,” Doubek wrote.

Healing meant many things to many people. Could a memorial accomplish such an enormous and daunting task? Could it heal the chasm within society, promote closure, show gratitude to those who served, comfort those in grief, and remind future generations of the toll wrought by war? Moreover, could it accomplish all of that while listing the approximately 58,000 names in an artistic, meaningful way?

Selecting a design that would meet the criteria demanded a jury that could grasp the significance of the Memorial’s purpose and understand the unique needs of Vietnam veterans, their families, and a country divided.

For weeks, heated discussions took place around the topic of who should be part of the design jury. Many felt it should be composed primarily of veterans; others felt it should be made up only of professionals; some thought a mix of the two would be best.

Ultimately, the VVMF Board agreed on a jury of the most experienced and prestigious artists and designers that could be found, since it took a mature eye to envision from two-dimensional renderings how a design would look when built. The reputation of the jurors was important to attract the best designers and to minimize second guessing by the Federal approval bodies

Spreiregen recommended having a multi-disciplinary panel: two architects, two landscape architects, two sculptors, and one generalist with extensive knowledge about art, architecture, and design. VVMF met the prospective jurors and scrutinized their credentials. “They found that they were very real people who did many of the same things they did,” recalled Spreiregen. “They were real guys. The VVMF group liked them all and approved of them with trust and enthusiasm,” even selecting three sculptors, making a total of eight jurors.

The jury included: architects Pietro Belluschi and Harry Weese; landscape architects Hideo Sasaki and Garrett Eckbo; sculptors Costantino Nivola, Richard Hunt, and James Rosati; and Grady Clay, a journalist and editor of Landscape Architecture magazine. Four of the eight were themselves veterans of previous wars.

Each juror was required to read Fields of Fire, A Rumor of War, and other current literature about the Vietnam War. “Many had worked together, some in Washington. They were also the most collegial people, who would deliberate intensely but never argue or posture,” Spreiregen remembered.

Launching the competition

With the jury selected, the next task was to announce and promote the competition. In the fall of 1980, VVMF announced the national design competition open to any U.S. citizen, who was over 18 years old.

By year’s end, 2,573 individuals and teams had registered – almost 3,800 people in total. From the registration forms, it was apparent that architects, artists, designers, as well as veterans and students — of all ages and all levels of experience — were planning to participate. They came from all parts of the country and represented every state. By the March 31, 1981, deadline, 1,421 design entries were submitted for judging.

With such an overwhelming response to the competition, logistics became an issue. End-to-end, the total number of submissions would have stretched one and one third linear miles. Each submittal had to be hung at eye level for review by the jury. But how and where could all of the submissions be displayed?

Vietnam veteran Joseph Zengerle, then an Assistant Secretary of the Air Force, volunteered the use of an aircraft hangar at Andrews Air Force Base. The added component of military security made the location even more attractive, since it would ensure no interference with the designs or the judging.

In accordance with the strict competition guidelines, anonymity of all designs was carefully observed. Each contestant sealed his or her name in an envelope and taped it to the back of the submission. The designs were received and processed in a large warehouse east of Washington. They were unwrapped, number coded, photographed for the record, and prepared for display.

By the March 31, 1981 deadline, 1,421 design entries had been submitted, making it the largest design competition of its kind ever held in the U.S. All entries were judged anonymously by a jury of eight internationally recognized artists and designers.

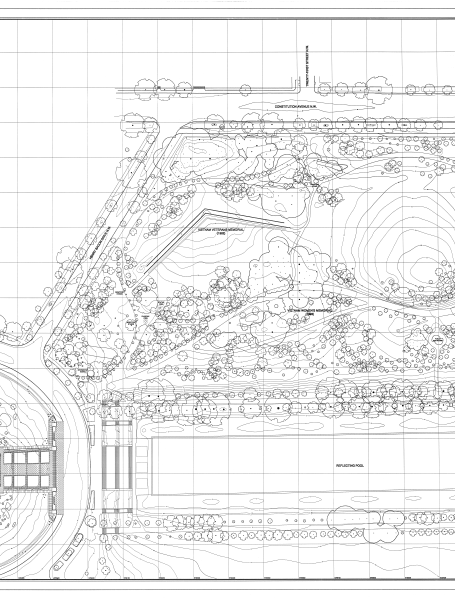

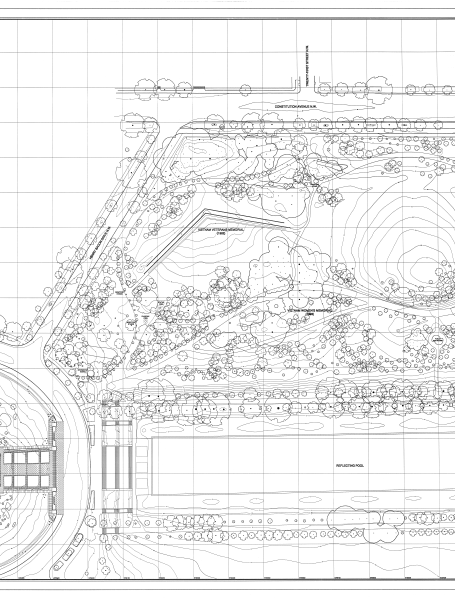

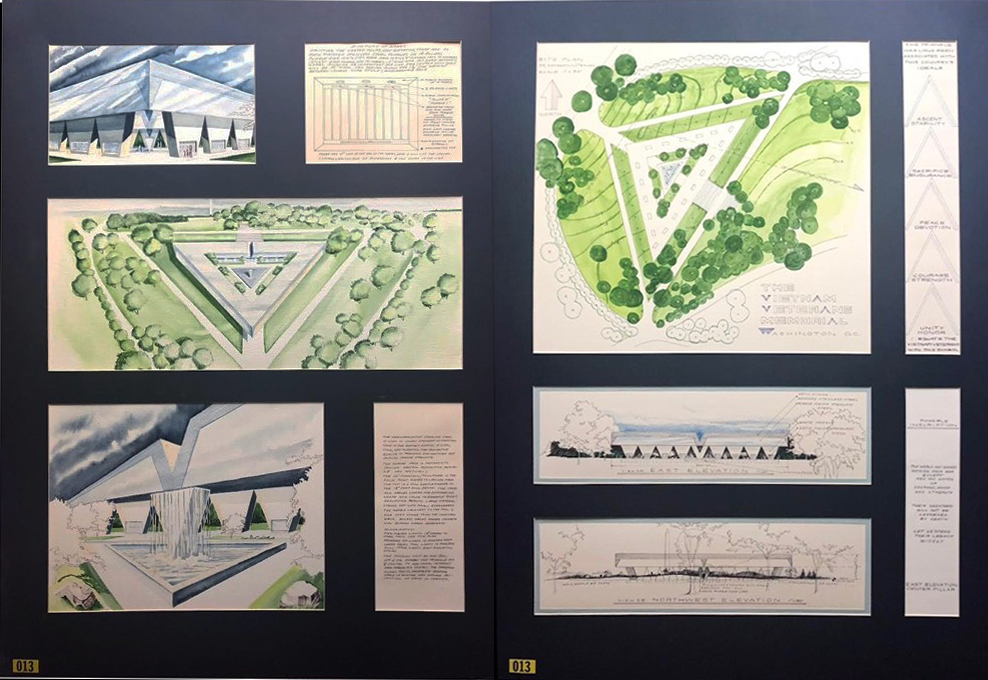

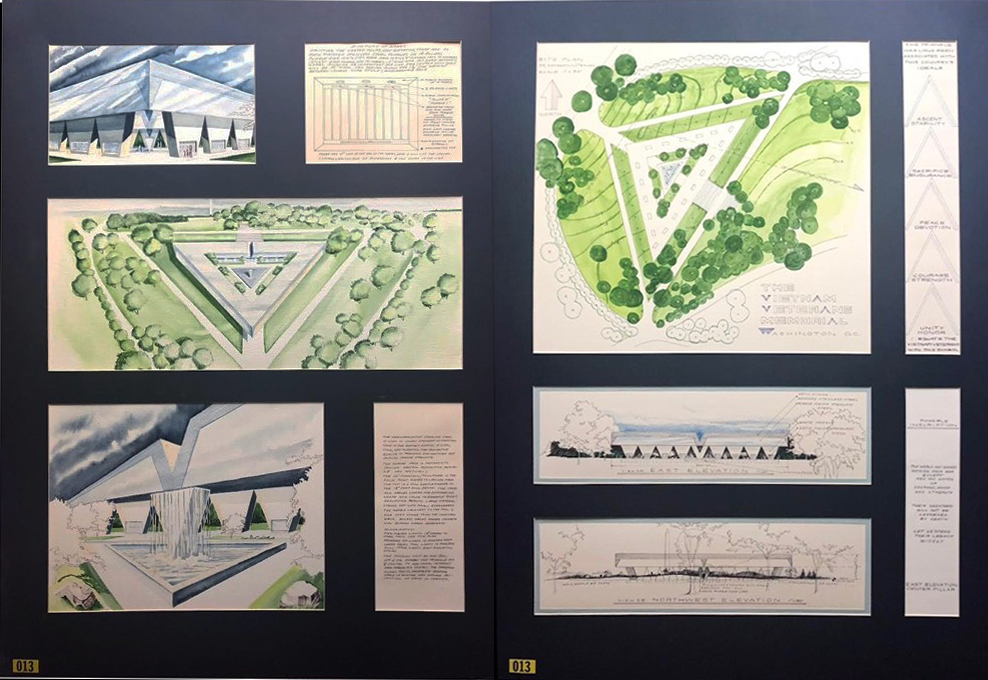

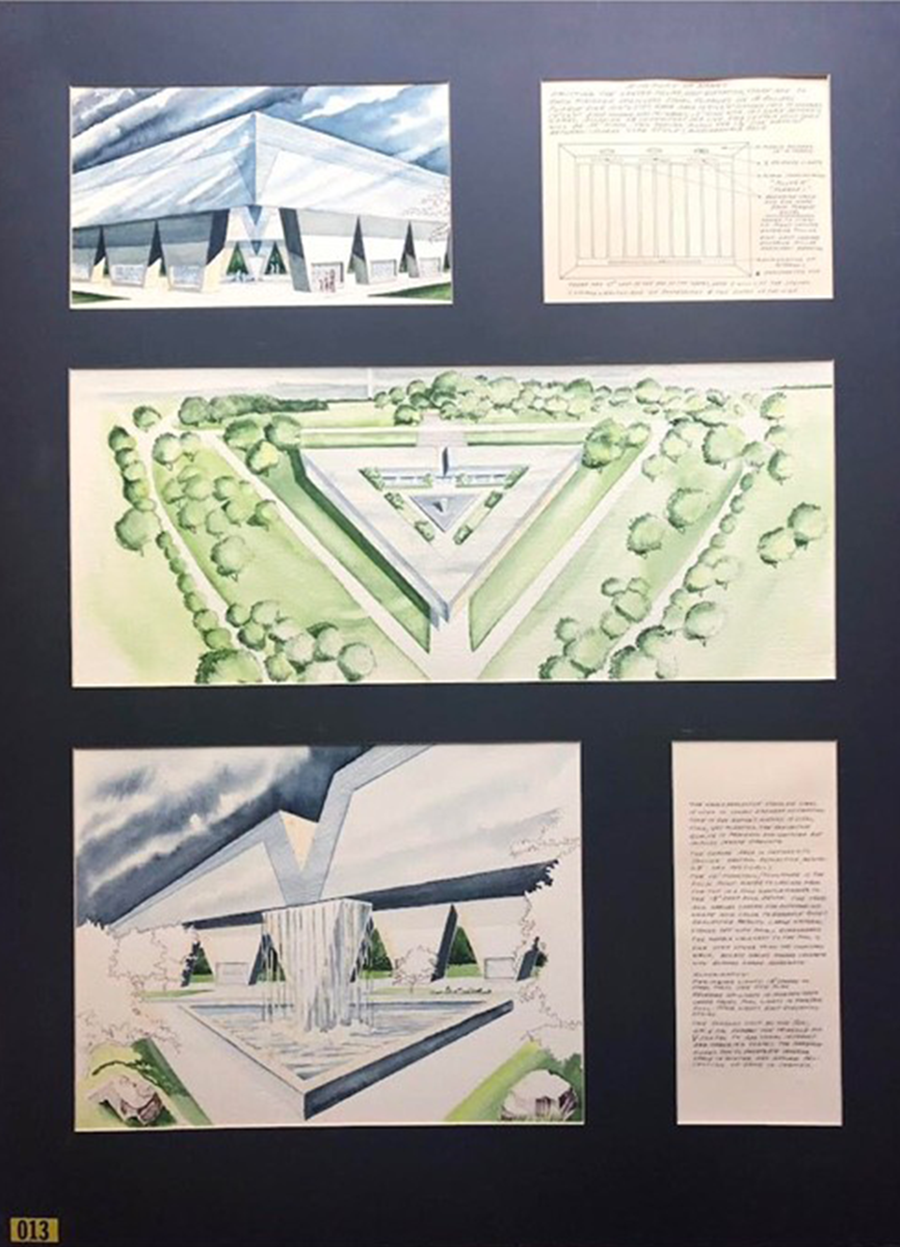

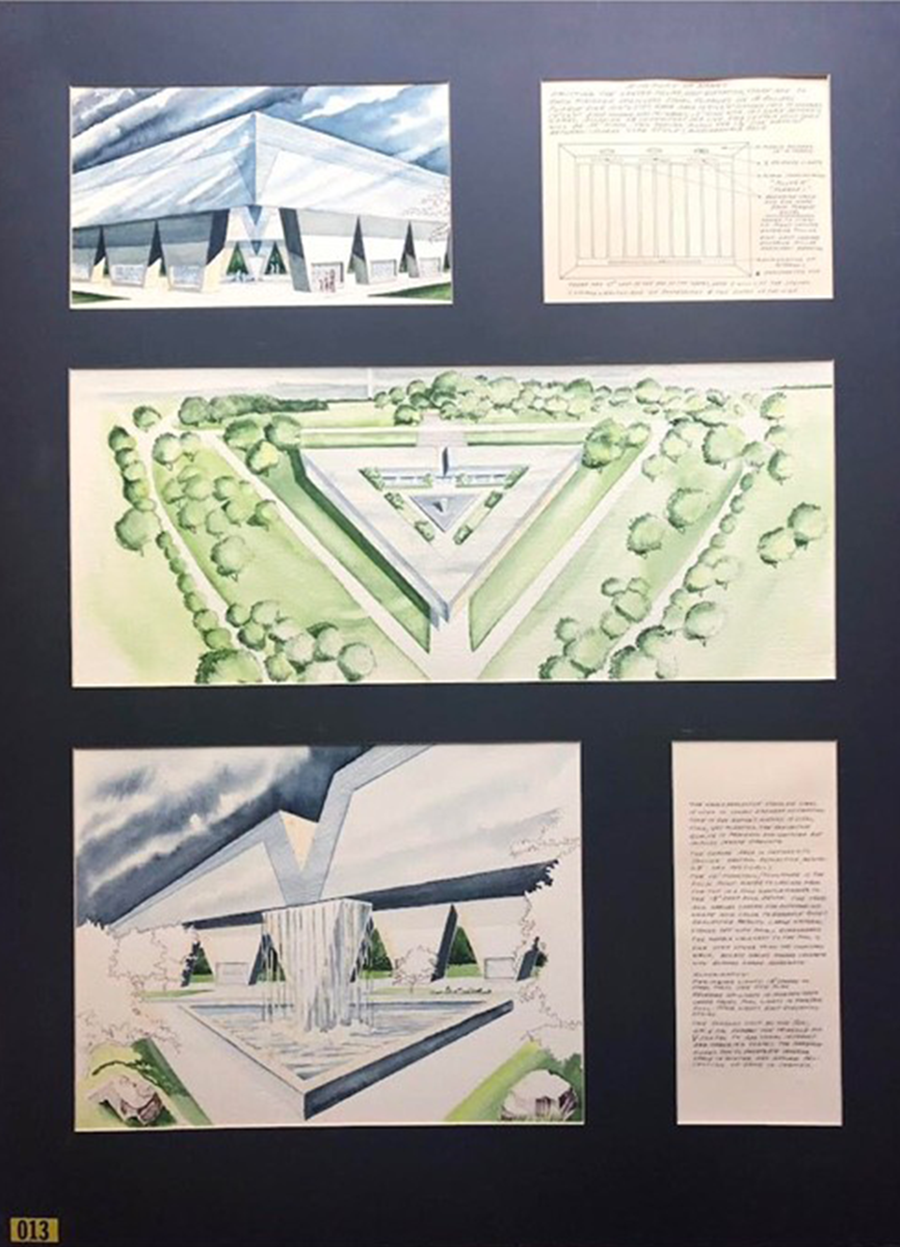

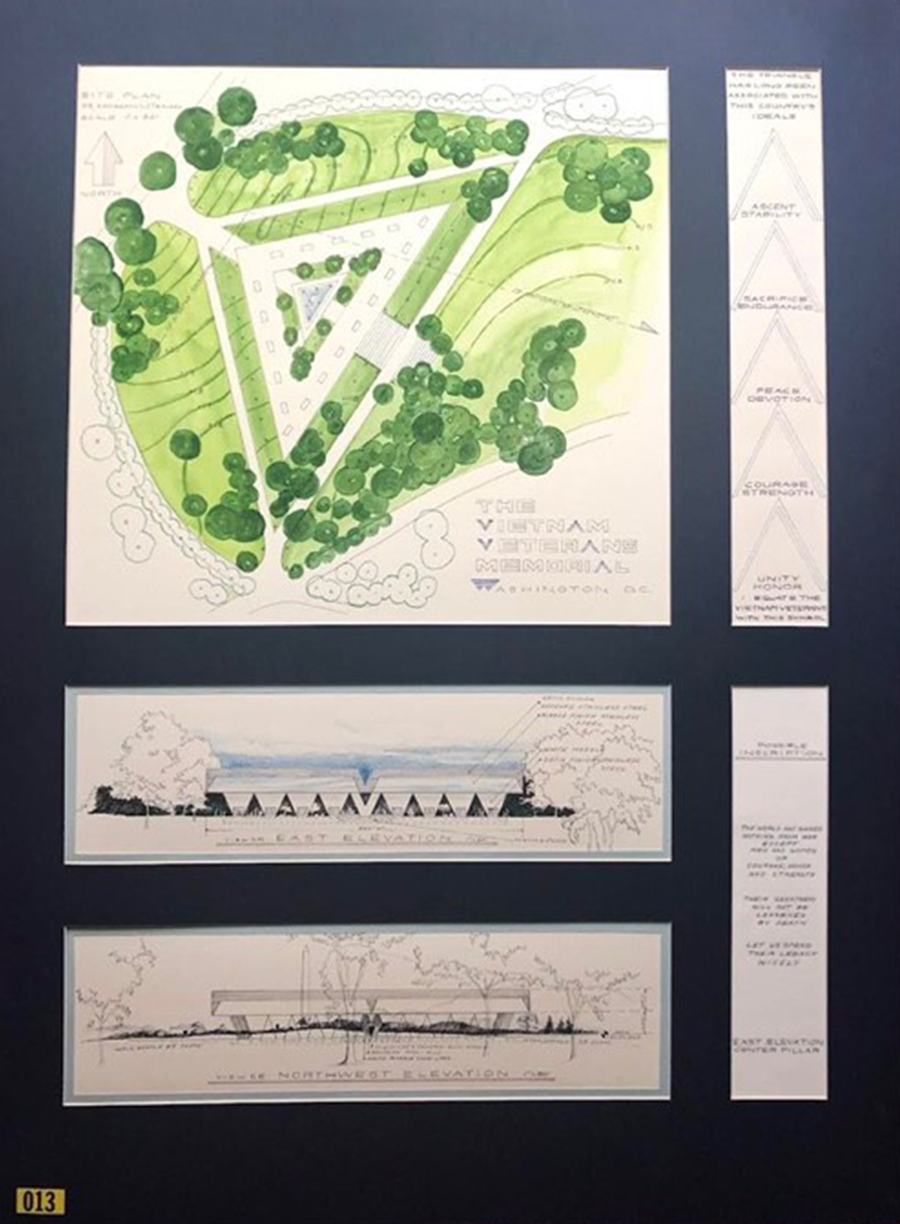

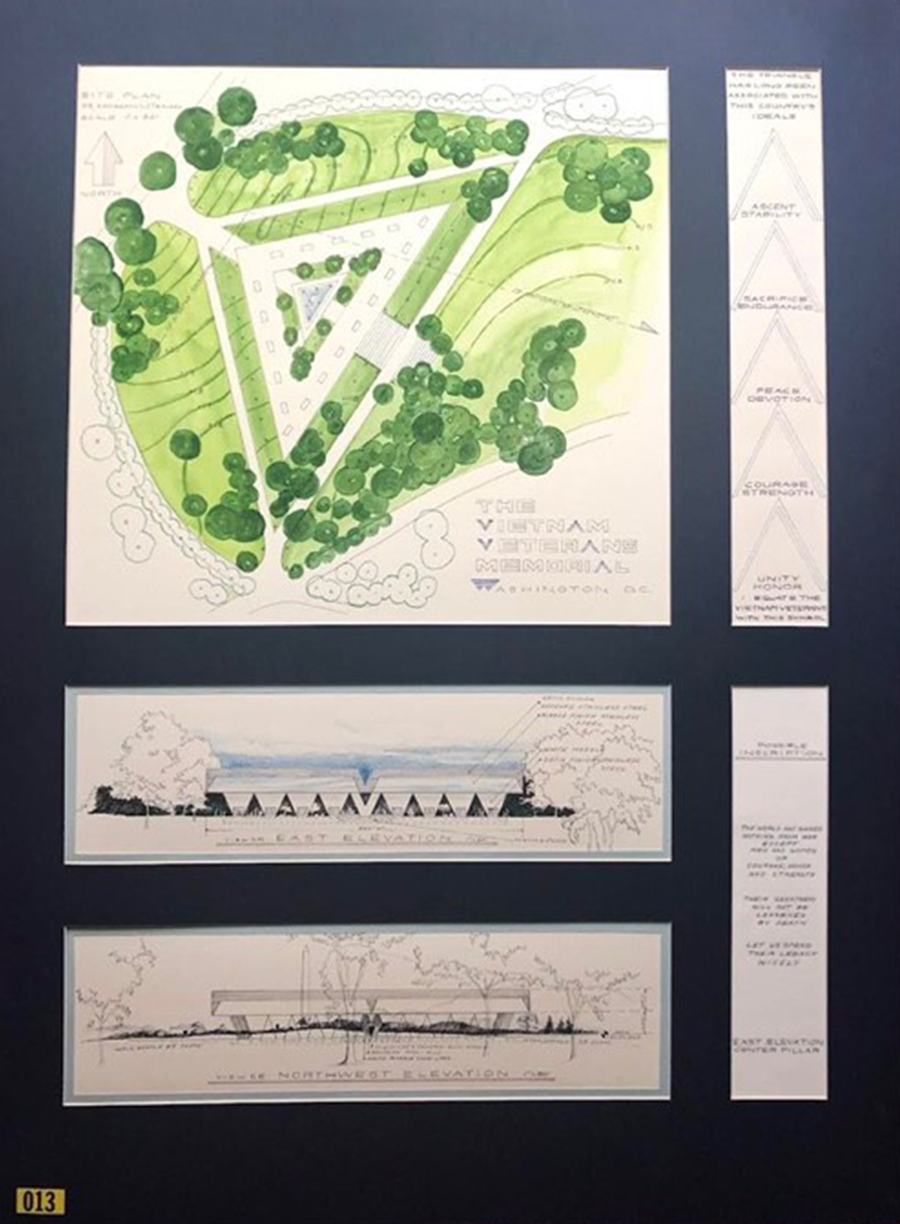

One of the 1,421 design entries that was submitted for the competition made its way to VVMF’s possession in 2024. The family of Delma Dee Schuldt graciously donated her submitted design along with the following note from her daughter Dana (Schuldt) Leahy:

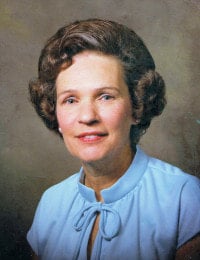

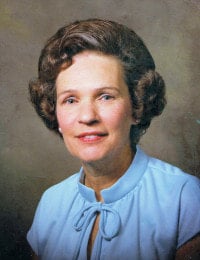

Delma Dee Schuldt Artist and VVMD Contest Entrant (circa 1981)

After 42 years of storing my mother’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial Design Contest original drawings in a comer of my basement, I decided to contact the VVMF and inquire about donating them to the VVMF. My mother, Delma Dee Schuldt, was one of 1,421 individuals (or design firms) who submitted a design for consideration in the VVMF’s contest in March of 1981. I was informed that no records exist regarding the placement of entrants, but I’d like to believe that she was a finalist since she was invited to attend a reception in Washington D.C. in May of 1981 where she was able to meet the contest winner Maya Lin and other contest finalists. I remember her referring to the experience as the “honor of a lifetime.” Unfortunately, she died 6 months later and was never able to see or visit the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

She was a gifted artist and architect whose father served as a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army and fought in WWI and WWII. In light of her military upbringing and patriotic nature, she was drawn to answer the call for entries when the VVMF announced the WMD contest. Her original designs are pictured below and reflect her elegant architectural style, her respect of symbology and the sacrifice made by veterans of every war.

Although she’s been gone for over four decades, I can’t think of a better way to honor my mother than to donate her designs to the VVMF, where they may be seen by others and may even inspire future generations to honor our veterans through the timeless gift of art.

(Note: VVMF is currently working on producing high quality scans of the submissions to be provided in the future)

The jury evaluation took place over five days, from April 27 through May 1, 1981. The jurors began by touring the site and then returned to Hangar #3 at Andrews to view each of the 1,421 designs individually.

“I had calculated that it was possible to see all of them in a minimum of 3 1/2 hours. The eldest juror, Pietro Belluschi, took a full day,” said Spreiregen. “By the end of the first afternoon, one of the jurors, Harry Weese, returned to our impromptu conference lounge and told me, ‘Paul, there are two designs out there that could do it.’

“On the second day, the jury examined the designs together, walking the many aisles and stopping at each of the 232 designs that had been flagged by one or more of the jurors, pausing to discuss each design that had been noted. The first cut was further reduced to 90 by midday Wednesday. By Thursday morning, it was down to 39. That afternoon, the winning design was selected,” said Spreiregen.

“It was the most thoughtful and thorough discussion of design that I have ever heard, and I have heard many,” he recalled.

With the winning design in hand, Spreiregen had less than 24 hours to craft an explanation of the decision—and the design—that would be suitable for presentation to VVMF.

Throughout the judging process, one of the judges, Grady Clay, had taken meticulous notes of the jury’s discussions. Together with Spreiregen, he composed a report based on these thoughtful comments.

“They are a treasure of design insight and included many prescient thoughts as to how the Memorial would likely be experienced,” Spreiregen wrote of Clay’s notes.

Some of the juror comments included:

“Many people will not comprehend this design until they experience it.”

“It will be a better memorial if it’s not entirely understood at first.”

“Confused times need simple forms.”

According to the description of the design concept: “The jury chose a design which will stimulate thought rather than contain it.”

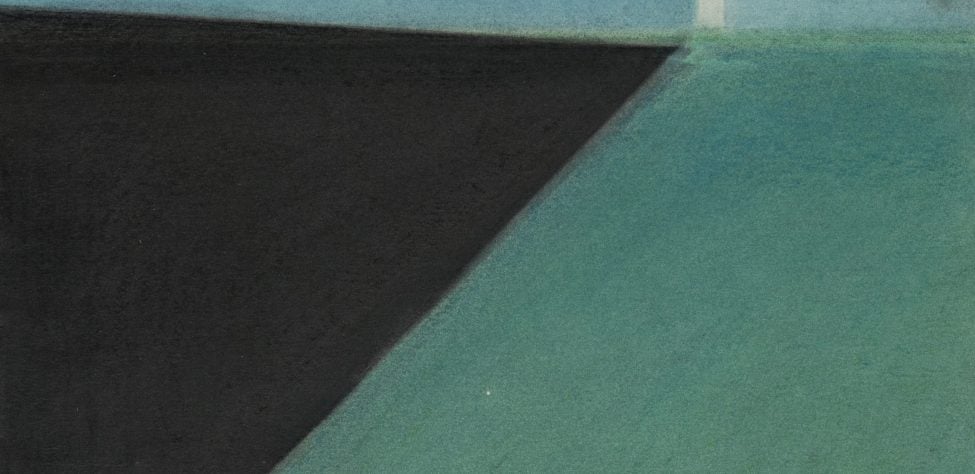

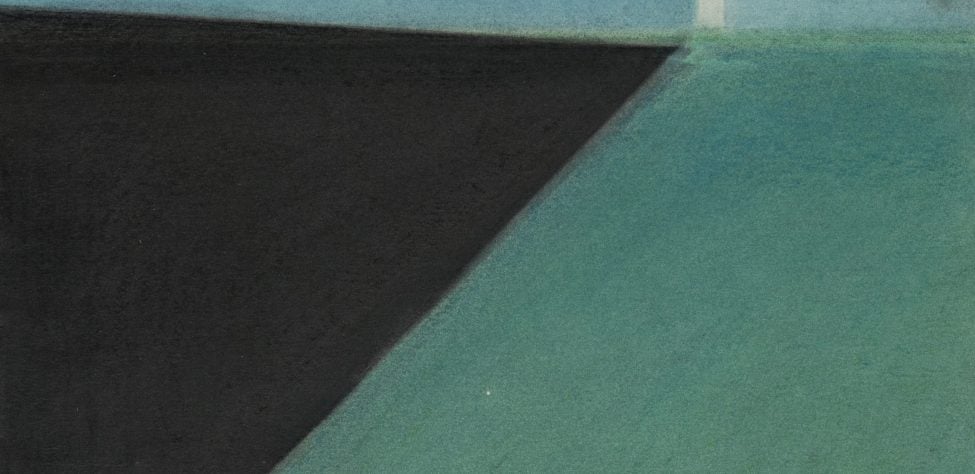

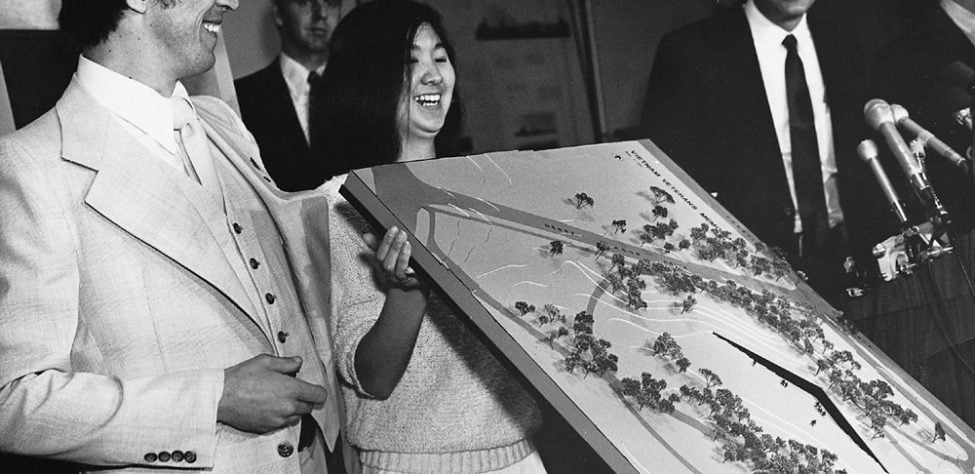

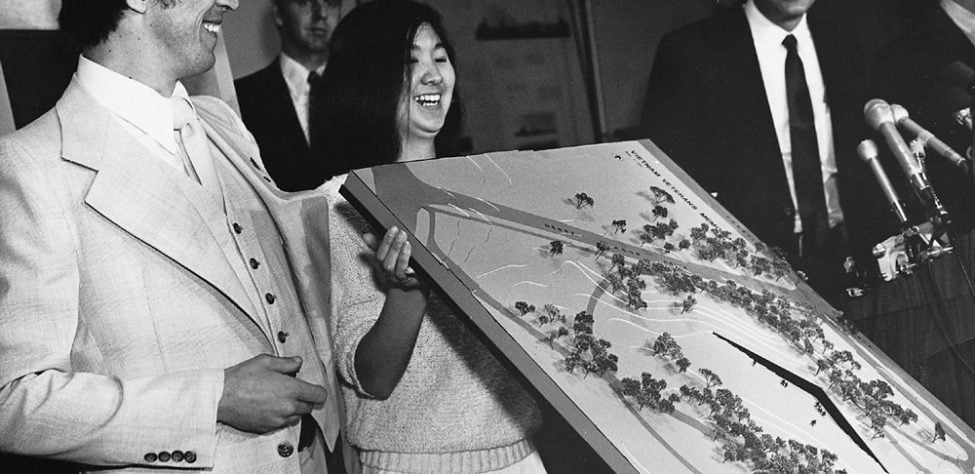

The winning design was the work of Maya Ying Lin of Athens, Ohio, a 21-year-old senior at Yale University. At 21 and still an undergraduate, Lin conceived her design as creating a park within a park — a quiet protected place unto itself, yet harmonious with the overall plan of Constitution Gardens. To achieve this effect she chose polished black granite for the walls. Its mirror-like surface reflects the images of the surrounding trees, lawns and monuments. The Memorial’s walls point to the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial, thus bringing the Memorial into the historical context of our country. The names are inscribed in the chronological order of their dates of casualty, showing the war as a series of individual human sacrifices and giving each name a special place in history.

In August of 1981, VVMF selected a building company and architecture firm to develop the plans and build Lin’s design. Lin became a design consultant to the architect of record.

Early on in the effort to get the Memorial built, there were traces of controversy. Some felt that the money to build a memorial could be better spent delivering the many services veterans needed. Others questioned the intent of the Memorial.

When VVMF announced the selection of Lin’s design, the initial public reaction was generally positive.

But several weeks after the announcement, a handful of people began to protest the design. A few of the most vocal opponents, including James Webb and H. Ross Perot, had previously been strong supporters of a memorial. They complained about the walls being black. They did not like the idea that it was below ground level. They did not like its minimalist design. They felt it was a slap in the face to those who had served because it did not contain traditional symbols honoring service, courage, and sacrifice. Some opponents simply did not like the fact that Lin was a young student, a woman, and of Asian descent; how in the world could she possibly know how to honor the service of the Vietnam veteran?

Then, in October 1980, veteran and lawyer Tom Carhart, also a former supporter, testified before the Commission of Fine Arts (CFA) against the design, saying that “One needs no artistic education to see this design for what it is, a black trench that scars the Mall. Black walls, the universal color of shame and sorrow and degradation.”

Lin moved to Washington and immediately became part of an internal struggle for control of the design. To bring the design into reality would require an architect of record. Lin and VVMF eventually selected the Cooper-Lecky Partnership as the architect-of-record, with Lin as the project’s design consultant.

A compromise

By early 1982, VVMF asked Warner to bring together both sides for a closed-door session to hammer out the issues.

An article by Hugh Sidey in the February 22, 1982, issue of TIME magazine described the session: “A few days ago, 40 supporters and critics of the memorial gathered to try to break the impasse that threatened the memorial because of such features as the black color of the stone and its position below ground level. After listening for a while, Brigadier General George Price, a retired veteran of Korea and Vietnam, stood in quiet rage and said, ‘I am sick and tired of calling black a color of shame.’ General Price, one of America’s highest-ranking black officers lived with and advised the 1st Vietnamese Infantry Division.

To Heal a Nation, a book written by Jan Scruggs and Joel Swerdlow about the creation of the Memorial, provides a vivid sketch of the scene:

“‘I have heard your arguments,’” said General Price. ‘I remind all of you of Martin Luther King Jr., who fought for justice for all Americans. Black is not a color of shame. I am tired of hearing it called such by you. Color meant nothing on the battlefields of Korea and Vietnam. We are all equal in combat. Color should mean nothing now.’”

Sidey’s piece continued: “At the end of five hours and much shouting, General Mike Davison, retired, who led the Cambodian incursion in 1970, proposed a compromise: add the figure of a soldier in front of the long granite walls that will bear the 57,709 names of those who died or are missing and the tribute to all who served. The battle was suddenly over.”

A new obstacle

VVMF agreed to the statue compromise, as well as to adding a flag and to reviewing the inscription on the Memorial, but they did not want to wait until a statue was designed before breaking ground. Waiting meant they would never reach their dedication deadline of November 11, 1982.

Over several tense weeks, more debate followed, until the Commission of Fine Arts (CFA) and the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) gave their approval for a statue and flag in concept, pending suitable placement of those elements. Watt followed on March 11, 1982, by granting permission for the construction permits.

With permit in hand, Doubek instructed to commence construction immediately. His reasoning was that a complete mess would make it tough to stop construction. Scruggs added: “Make this place look like an airstrike was called in,” he instructed. “Rip it apart.”

An official groundbreaking ceremony was held on March 26, 1982. General Price, along with Senators Warner and Mathias and future Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel, gave moving addresses before the command was given, and 150 shovels entered the ground with enthusiastic veterans enjoying the moment.

As soon as the design was chosen, the next step was to consider the all-important details of getting it built.

Maya Lin worked closely with Cooper-Lecky on all aesthetic aspects of the design. Lin knew it was critical to maintain the simplicity of the design throughout the design development and construction process.

Choosing the granite

As the selection of the granite was narrowed down, Lin was keen on preserving the notion that the granite walls be reflective and thin – to help express a critical aspect of the design – that the memorial was a cut in the earth that had been polished.

Working with the construction manager, Gilbane Building Company, the design team had to locate the appropriate type of granite: a flawless, reflective, deep ebony stone. In the end, the quarry in India was selected.

Finalizing the size

The choice of the lettering style – Optima, designed by Hermann Zapf – was a font Lin selected after considering a multitude of options.The font Optima seemed to fit that desire to match an almost printed quality with a hand-cut feel.

The entire text size and layout Lin saw as an open book.

The text size is less than half an inch, which is unusual for monument design, but was selected to make the memorial read more like a book. This lends a sense of personal intimacy in a public space which helps create a sense of connection to the memorial.

Ultimately, one of the greatest challenges was how to get that many names on the wall panels in such a short period of time.

Inscribing the names

The design Lin envisioned listed the names chronologically by date of casualty. However, that posed a problem of how to locate an individual name. When Lin asked how many Smiths would be on The Wall, the team realized how important the chronological listing was to the design.

A chronological listing would also allow a returning veteran to find his or her time of service on The Wall and those who died together to remain together forever on The Wall. The solution on how to locate a name evolved into a directory of names with an alphabetical listing and the panel and line number of each name.

The families of service members who were missing in action originally wanted their names listed separately. Ms Lin arrived at a design solution to note those that were MIA with a symbol (†) that could be altered if the service member was found.

The original design proposal called for all of the names to be individually hand-chiseled in the stone, but it was soon realized the time and money it would take to do that were impractical. Instead, Lin found John Benson, a master stonecutter, to hand cut the text at the apex – the years of the earliest and latest casualties from the Department of Defense list and the brief prologue and epilogue adjacent to the dates. The design team and VVMF searched for a way for the names to be sandblasted rather than hand-carved.

Larry Century, a young inventor from Cleveland, Ohio, was selected to serve as a consultant to Binswanger Glass Company in Memphis, Tennessee, which was awarded the contract for inscribing the names.

Crowd at the dedication of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, 1982. Photo by William “Bill” Lecky

As soon as ground was broken for The Wall in March 1982, planning for its dedication ceremonies began. They would include a big National Salute to Vietnam Veterans at Veterans Day. The American Legion, VFW, Disabled American Veterans (DAV), AMVETS, and Paralyzed Veterans of America (PVA) made sure their members knew that veterans were going to be honored and welcomed that week on the National Mall. More than 150,000 veterans, families, loved ones and friends made plans to attend.

The series of events began on Wednesday, November 10, 1982, and culminated with a service at the National Cathedral on Sunday, November14.

The Salute opened with a vigil Wednesday morning at the National Cathedral, where all of the nearly 58,000 names on The Wall were read by volunteers around the clock, day and night, through midnight Friday. Every 15 minutes, there was a pause for prayer.

On Saturday, a grand parade took place where veterans marched joyously out of sync, some hand-in-hand or with their arms draped around one another, holding banners, flags, and signs. Many pushed friends in wheelchairs. The following week, Kurt Anderson recapped the festivities for TIME magazine: “Saturday’s three-hour parade down Constitution Avenue, led by [Gen. William] Westmoreland, was the vets’ own show. The 15,000 in uniforms and civvies, walked among floats, bands and baton twirlers. The flag-waving crowds even cheered.”

Over the four days there were also workshops, parties, events, and reunions. “It was like a Woodstock atmosphere in Washington for those who had served in Vietnam,” recalled Scruggs. “After three-and-a-half years of nonstop effort and work, with all that you have to do to accomplish what we did, it was beautiful. It was surreal.”

“The whole week was extremely emotional,” Becky Scruggs remembered. “It was a whirlwind of events, and the press coverage was unbelievable. I remember The Washington Post had pages and pages of stories in the ‘A’ section.” Vietnam veterans were, at long last, receiving the recognition they deserved.

Woods remembered, “I was like the kid at FAO Schwartz. I was dumbfounded that we had succeeded at doing this. The controversy overshadowed the mission and what we were doing,” until the Salute brought it all together.

After the dedication, Scruggs and Wheeler walked together along the upper side of the Memorial ground, near Constitution Avenue. Although thousands of people were there, “It was so very quiet,” Wheeler recalled. “I just kept thinking to myself how quiet it was, and yet there was an immense feeling of community. It was becoming apparent that we had been able to be instruments to something far greater than anything we had ever imagined.”

The love and acceptance that the American people gave to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial have continued unabated for over 25 years. Today, The Wall continues to be the most-visited memorial on the National Mall, attracting more than five million people each year.

From the beginning, people have left tributes at its base. Medals, toys, flowers, photographs—anything and everything is left at The Wall as family and friends seek to remember their loved ones who made the ultimate sacrifice in Vietnam.

The National Park Service archives most of the nonperishable items left at The Wall. Every day, park rangers collect and tag the items, noting which wall panel each item was left beneath. All of these items are stored in a museum-quality facility in Landover, Maryland.

Maya Lin, has gone on to become a respected architect and artist, with a studio in New York City. She is still remembered fondly by veterans for the moving Memorial she designed for them.

“After 25 years, the way in which visitors have embraced and cherished this work has been a great gift to me,” she wrote in the program for the 25th anniversary ceremony. “I am always incredibly moved and heartened, especially when a veteran tells me that The Wall has helped them in some way—it could not mean more to me.

“When I meet Vietnam veterans who stop me to say thank you for creating the Memorial, I always want to say: thank you, for the service and sacrifices that all of you have made in service to your country,” she added.