Overview

During American involvement in Vietnam, hundreds of American service members were shot down, captured, and taken prisoner by North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces.

On March 26, 1964, U.S. Army Colonel Floyd James Thompson was a passenger on an observation mission when his aircraft was shot down by small arms fire. He was captured by National Liberation Front (Viet Cong) forces and spent nearly nine years in captivity, making him the longest-held prisoner of war in American history. On August 5, 1964, Navy Lt. Everett Alvarez became the first U.S. pilot to be shot down and detained after participating in a retaliatory strike on strategic points in North Vietnam as a result of the Gulf of Tonkin Incident. He would spend more than eight years in captivity, making him the second longest-held U.S. POW.

From 1964 until the final release of POWs in 1973, North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces had captured Americans, mostly pilots and airmen of downed aircrafts. American POWs were held in prison camps in brutal conditions. They were tortured, beaten, and isolated. Many suffered from disease, psychological deprivation, and malnutrition. Some prisoners died in captivity, from wounds sustained in combat or at the hands of their captors. American POWs learned ways to communicate with each other, including using the Tap Code which involved tapping on their cell walls. The most notorious prison was the Hoa Lo prison, known by most Americans as the “Hanoi Hilton.”

The POW/MIA issue became a major focal point during the Vietnam War with many families becoming relentless advocates for the fullest possible accounting of those missing. The creation of POW/MIA bracelets and the POW/MIA flag continued to bring national awareness to the issue. The National League of POW/MIA Families was formed on May 28, 1970. The League’s mission is to obtain the release and return of all prisoners, the fullest possible accounting for the missing, and the repatriation of remains of those not yet recovered who died while serving our nation.

On January 27, 1973, the Paris Peace Accords were signed. One of the conditions stated that all American POWs were to be released to the United States. On Feb. 12, 1973, U.S. prisoners of war began their journey back to U.S. soil as part of Operation Homecoming. At the time, the U.S. listed 2,646 Americans as unaccounted for from the war. Since 1973, the remains of more than 1,000 Americans killed in the Vietnam War have been identified and returned to their families. The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency currently works to recover the remains of U.S. military personnel from the Vietnam War, as well as other conflicts.

Of the more than 58,000 service members with names inscribed on The Wall, approximately 1,500 are still listed as Missing in Action. Beside each name on The Wall is a symbol designating status. The diamond symbol denotes that the service member is known dead or presumed dead. The cross symbol denotes that the service member was missing or prisoner status when The Wall was built in 1982 and remains unaccounted for today. When a service member is repatriated, the diamond is superimposed over the cross.

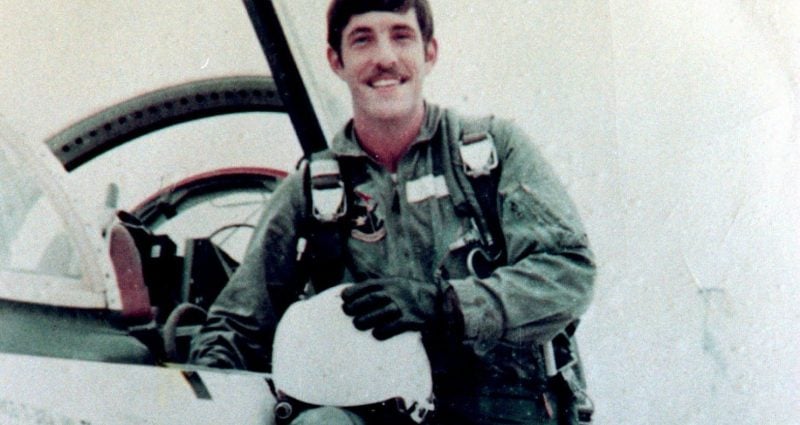

Robert Shumaker

Born in 1933 in New Castle, Pennsylvania Robert Shumaker (Bob) graduated from the US Naval Academy in 1956, and went on to marry Lorraine Shaw in 1963. In 1965, while flying an F8 Crusader, Shumaker became the second airman to be shot out of the sky over North Vietnam, his parachute barely opening before hitting the ground. He was picked up and brought to the Hoa Lo Hilton, the prison he would later humorously dub, The Hanoi Hilton. Shumaker endured a broken back from his parachute fall, but was denied medical treatment. Eventually the painful injury healed on its own, but for six months Shumaker struggled to walk and remained in excruciating pain.

During his eight years in captivity Shumaker helped coin the nickname the Hanoi Hilton, was involved in the creation of the Tap Code, an elaborate system created to allow US POW’s communicate through their cells and in person without their captors becoming aware, and was part of a group remembered as the Alcatraz Gang. The Alcatraz Gang-separated from the regular prison population at the Hanoi Hilton this group of Navy and Airforce officers- were thought to be extremely resilient and defiant in the face of their NVA captors. They were placed in solitary confinement and endured extra rounds of torture based on rank and age. Upon homecoming in 1973 Shumaker Shumaker attended US Naval Post Graduate School, receiving a PhD in Electrical Engineering and retiring in 1988 from the Pentagon at the rank of Rear Admiral.

Awards:

Admiral Shumaker’s military decorations include the Distinguished Service Medal, two Silver Stars, four Legions of Merit, the Distinguished Flying Cross, a Bronze Star, and two Purple Hearts. In 2011 he was presented with the Distinguished Graduate Award from the U. S. Naval Academy.

POW/MIA recognition Day

Until July 18, 1979, no special commemoration was held to honor America’s POW/MIAs, those returned and those still missing and unaccounted for from our nation’s wars. That first year, resolutions were passed in Congress and the national ceremony was held at the National Cathedral, Washington, DC. A Missing Man Formation was flown by the 1st Tactical Squadron, Langley AFB, Virginia. The Veterans Administration published a poster with the letters “POW/MIA” and that format was continued until 1982, when a black and white drawing of a POW in harsh captivity was used to convey the urgency of the situation and the priority that President Ronald Reagan assigned to achieving the fullest possible accounting for Americans still missing from the Vietnam War. For the next ten years, the various renditions of the American Eagle, by artist and Vietnam Veteran Tom Nielsen, came to symbolize America’s POW/MIAs and our nation’s determination to account for them and bring them home.

National POW/MIA Recognition Day legislation was introduced yearly until 1995 when Congress opted to discontinue considering legislation to designate special commemorative days. Since then, successive Presidents have signed an annual proclamation. In the early years, the date was routinely set in close proximity to the League’s annual meetings. In the mid-1980’s, the American Ex-POWs decided that they wished to see the date established as April 9th, the date during World War II when the largest number of Americans were captured. As a result, legislation advocated by the American Ex-POWs was passed covering two years, July 20, 1984, as initially proposed, and April 9, 1985, the latter of which had to be cancelled due to inclement weather, a concern that had been expressed with the proposed April 9th date.

The 1984 National POW/MIA Recognition Day ceremony was held at the White House, hosted by President Reagan. At this most impressive ceremony, the Reagan Administration balanced the focus to honor all returned POWs and renew national commitment to accounting as fully as possible for those still missing. Perhaps the most impressive Missing Man Formation ever flown was that year, up the Ellipse and directly over the White House.

Subsequently, in an effort to accommodate all returned POWs and all Americans still missing and unaccounted for from all wars, the League proposed the third Friday in September, a date not associated with any particular war, not in conjunction with any organization’s national convention, and a time of year when weather nationwide is usually moderate. Most national ceremonies have been held at the Pentagon; however, in addition to the July 20, 1984, White House ceremony noted above, the September 19, 1986, national ceremony was held on the steps of the US Capitol facing the National Mall, also concluding with a flight of high performance military aircraft in Missing Man Formation.

National POW/MIA Recognition Day ceremonies are now held throughout the nation and around the world on military installations, ships at sea, state capitols, at schools, churches, national veteran and civic organizations, police and fire departments, fire stations, etc. The League’s POW/MIA flag is flown, and the focus is to ensure that America remembers its responsibility to stand behind those who serve our nation and do everything possible to account for those who do not return.

Information courtesy of the National League of POW/MIA Families

National POW/MIA Recognition Day – 2020 from Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund on Vimeo.

Hal Kushner

Hal Kushner enrolled in the US Army while a medical student at the Medical College of Virginia in 1965. In August of 1967 he deployed to Vietnam as an Army Flight Surgeon. Not four months later during a dark and rainy evening Kushner was aboard a helicopter that crashed in to the side of a mountain in South Vietnam, leaving only himself, the copilot, and the crew chief as survivors. The next day the crew chief walked down to find help while Kushner and the wounded copilot did as the men had been instructed and stayed with the downed aircraft hoping that rescue would come soon. Then the copilot died and the crew chief did not return, having been shot just ten miles away. Kushner realized that he would soon need food if he were to survive. Upon crashing Kushner had received a broken arm, collar bone, and multiple wounds from an M-60 that fired while the aircraft was engulfed, yet he managed to belt strap his arm to his side and walk down the mountain in search for help. Kushner was quickly picked up by enemy soldiers and although he showed them his Geneva Convention card declaring himself a noncombatant they pulled him away shouting, “POW, POW, criminal”.

Kushner spent the next few years in the jungles of South Vietnam, surviving with other POW’s on spoiled rice and incredibly desolate conditions. In 1971 Kushner and the other men in his jungle prison were moved 560 miles over 57 days to the POW camp called the Hanoi Hilton where he remained until March of 1973. When released Kushner returned home to his wife and children and remained in the Army until 1986 when he retired at the rank of colonel.

The POW / MIA Flag

(Revised August 18th 2020)

In 1970, MIA wife and member of the National League of POW/MIA Families, Mrs. Michael Hoff, recognized the need for a symbol of our POW/MIAs. Prompted by an article in the Jacksonville, FL, Times-Union, Mrs. Hoff contacted Norman Rivkees, Vice President of Annin & Company, which had made a banner for the newest member of the United Nations, the People’s Republic of China (PRC), as part of their policy to provide flags of all UN member states. Mrs. Hoff found Mr. Rivkees very supportive of POW/MIA accounting efforts; he and contracted employee Newt Heisley came up with our Vietnam War POW/MIA flag design.

After the League’s Board of Directors approved the design on January 22-23, 1972, POW/MIA flags were manufactured for distribution. To ensure the widest possible dissemination and use of this symbol to advocate for improved treatment for America’s POWs and answers on our MIAs, no trade mark or copy-right was sought. As a result, extensive use of the League’s POW/MIA flag is not restricted legally. The large volume of commercial production and sales required to meet demands of federal and state laws does not benefit the League financially

The importance of the POW/MIA flag lies in its visibility as a constant reminder of America’s UNRETURNED VETERANS. Other than “Old Glory,” our POW/MIA flag is the only flag ever to fly over the White House, first displayed in this place of honor by President Ronald Reagan on National POW/MIA Recognition Day, 1982.

On March 9, 1989, an official League flag – flown over the White House on National POW/MIA Recognition Day 1988 – was installed in the US Capitol Rotunda after legislation passed overwhelmingly during the 100th Congress. In a demonstration of further bipartisan Congressional support, the leadership of both Houses hosted the installation ceremony, at which Ann Mills-Griffiths, then League Executive Director, now Chairman of the Board/CEO, delivered remarks representing the POW/MIA families.

The League’s POW/MIA flag is the only flag ever displayed in the US Capitol Rotunda where it stands as a powerful symbol of America’s determination to account for US personnel still missing and unaccounted-for from the Vietnam War. On August 10, 1990, the 101st Congress passed bipartisan legislation and President George H.W. Bush signed PL 101-355, recognizing our POW/MIA flag and designating it “the symbol of our Nation’s concern and commitment to resolving as fully as possible the fates of Americans still prisoner, missing and unaccounted for in Southeast Asia, thus ending the uncertainty for their families and the Nation”.

On November 7, 2019, President Donald J. Trump signed PL 116-67, amending Title 36, Section 2 (Days on Which the POW/MIA Flag is Displayed on Certain Federal Property), and Subsection 902(c) (Days for Flag Display). For the purposes of these sections, POW/MIA flag display days are all days on which the flag of the United States is displayed. The Federal property locations where the POW/MIA flag must be displayed in a manner visible to the public are: The US Capitol; the White House; the WWII Memorial; the Korean War Veterans Memorial; the National Vietnam Veterans Memorial; each national cemetery; buildings containing the offices of the Secretaries of State, Defense, and Veterans Affairs; office of the Director of the Selective Service System; each major military installation as designated by the Secretary of Defense; each Veterans Affairs medical center; and each office of the US Postal Service. Most states have adopted similar laws as have local governments nationwide.

Public Law 116-67 designates the League’s POW/MIA flag “as the symbol of the Nation’s concern and commitment to achieving the fullest possible accounting of Americans who, having been prisoners of war or missing in action, still remain unaccounted for; and . . . Americans who in the future may become prisoners of war, missing in action, or otherwise unaccounted for as a result of hostile action.”

LEAGUE POLICY ON POW/MIA FLAG DISPLAY was adopted at the League’s 32nd Annual Meeting in June 2001. Members present overwhelmingly passed the following resolution: “Be it RESOLVED that the National League of POW/MIA Families strongly recommends that state and municipal entities fly the POW/MIA flag daily to demonstrate continuing commitment to the goal of the fullest possible accounting of all personnel not yet returned to American soil.”

Information courtesy of the National League of POW/MIA Families

David Harker

David Harker was born in Lynchburg Virginia in December of 1945. He was drafted into the US Army and deployed for Vietnam in November of 1967. Harker was captured with three other Americans during an ambush near Quang Tin Province in January of 1968. He survived a stab wound from a bayonet to his side. For the next three years Harker was held in the jungles of South Vietnam. Harker and other prisoners were held in jungle camps with deplorable conditions and no access to clean food, water or adequate health care. Harker remembers watching many other POW’s die in the camp and suffered himself from a debilitating skin condition. Harker also recalls sharpened bamboo lining the perimeter of the camps threatening a painful death to anyone who might try and escape. In 1973 after 1,884 days in captivity David Harker was released. He left the Army after that and enrolled back in school, graduating and serving for 30 years on the Virginia Parole Board.

The Unknown Soldier

U.S. Air Force 1st Lt. Michael Blassie was once known as the Vietnam War “Unknown Soldier”.

On Memorial Day in 1984, a set of unidentified remains were interred in the Tomb of the Unknowns, alongside remains of service members from WWI, WWII and the Korean War at Arlington National Cemetery. Those “unknown” remains, later identified as Michael Blassie, became representative of those who remained unaccounted for in Southeast Asia.

On May 11, 1972, Blassie was flying an A-37B Dragonfly aircraft when it was hit by ground fire near An Loc, 60 miles outside of Saigon. His wingman witnessed an explosion and there was no indication that Blassie survived. Blassie was then listed as missing-in-action for more than a decade. He was 24 years old. Blassie’s remains were taken “home” to the United States in 1984 but they were not positively identified, and instead were interred at the Tomb of the Unknowns. Forensic technology was limited at the time, preventing positive identification.

Michael Blassie was born on April 4, 1948, in St. Louis, Missouri to George and Jean Blassie. He was the oldest of five children. In 1970, Blassie graduated from the U.S. Air Force Academy and went on to serve as a 1st Lieutenant with the 8th Special Operations Squadron in Vietnam.

Recovery of Blassie’s crash site took nearly six months after bone fragments, an ID card, and a radio were found at the crash site. While the remains found at the crash site were initially identified as Blassie’s, forensic miscalculations about the height and weight of the bones caused them to be reclassified as unknown and labeled “X-26.”

In a ceremony at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii on May 17, 1984, X-26 was officially classified as the remains of the “Unknown Soldier” from Vietnam and sent to the United States aboard the U.S.S. Brewton.

The remains were then sent to Travis Air Force Base on May 24, and arrived at Andrews Air Force Base the following day. Many Vietnam veterans, President Ronald Reagan, and First Lady Nancy Reagan visited X-26 as he lay in state in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda for three days. On Memorial Day, May 28, 1984, X-26 was escorted to Arlington National Cemetery. A funeral was held and President Ronald Reagan presented the Medal of Honor to the Vietnam Unknown. The President also accepted the interment flag at the end of the ceremony.

Ten years later in 1994, a former Army Green Beret Ted Sampley called the Blassie family and said he had written an article for the Vietnam veterans’ newsletter proving that Blassie was buried in the Tomb of the Unknowns.

Media attention increased around Blassie and on Jan. 19, 1998, the CBS Evening News aired the story. Air Force Lt. Michael J. Blassie WAS the Vietnam Unknown buried in Arlington Cemetery, Eric Engberg reported. The military for years had used the secrecy of the selection process, he claimed, to hide Blassie’s identity from his family and the public.

After Blassie’s family secured permission and petitioned the Department of Defense to open the site and conduct DNA testing, the remains of X-26 were exhumed on May 14, 1998. As a result of mitochondrial DNA testing, scientists were able to match X-26’s DNA to Michael Blassie’s mother and oldest sister.

On June 30, 1998, the Defense Department announced that the Vietnam Unknown had been identified.

At the request of the family, Blassie’s remains were removed from the Tomb of the Unknowns. On July 11, 1998, 1st Lt. Michael Blassie was buried with full military honors in Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery in Missouri.

While X-26 was awarded the Medal of Honor when he was interred in the Tomb of the Unknown at Arlington National Cemetery, it was rescinded when the remains were identified as Michael Blassie.

Michael Blassie’s name is inscribed on Panel 1W, Line 23 of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

THE VIETNAM WAR'S FIRST AVIATOR POW

On August 5, 1964, Everett Alvarez was flying over North Vietnam when his plane was shot down and he became the first aviator POW of the Vietnam War. Alvarez was captured and taken to Hao Lo prison. From that day until the final release of POWs in March of 1973, service members were shot down, captured, and taken prisoner by North Vietnamese forces.

The Hero Bike

Many items have been left at The Wall to honor and remember those still Missing in Action – including one of the largest items ever left at The Wall – the “Wisconsin Hero Bike.” Referred to as simply the “Hero Bike” or the “Wisconsin Rolling Memorial,” this custom-built chopper motorcycle was conceived in honor of the 37 Wisconsin service members listed by the Department of Defense as MIA at the time of production.

Spearheaded by members of the “Bike for The Wall Committee,” a group of Wisconsin Vietnam veterans and motorcycle enthusiasts, construction on the bike began in Wisconsin in June 1994 with donations of cash and parts from supporters throughout the state. The bike is tagged with a license plate reading, “HERO,” a plate registered in April 1994 to the people of Wisconsin. In design, the chopper incorporates the names of each of the ‘Wisconsin 37’ in the paint schemes. A commemorative dog tag for each of the honored Wisconsin MIAs is also affixed to the frame of the bike. No one is permitted to sit on or to ride the Hero Bike until each of the ‘Wisconsin 37’ can be accounted for and their fates made known.

As a part of Rolling Thunder VIII / Run To The Wall ’95 the bike left Wisconsin on May 25th and reached The Wall in Washington, D.C. on May 27th where it remained on public display for three days during the Memorial Day holiday. On May 29, 1995, the bike was delivered to the National Park Service’s Museum Resource Center and was formally accessioned into the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Collection of items left at The Wall.

A Father's Story

Colleen Shine, who’s father and uncle both made the ultimate sacrifice during the Vietnam War, discusses her father’s story and legacy.

ANTHONY CAMERON SHINE is honored on Panel 1W, Row 93 of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

The Wall That Heals

Unlike previous wars, the families of prisoners of war and missing service members organized to ensure their loved ones would not be left behind. POW/MIA bracelets were created to bring attention to the issue and have been worn by millions with bracelets being created for subsequent wars. These bracelets represent men who eventually came home alive, those whose remains have been recovered and repatriated, and those we have yet to find and whose families continue to wait.

POW/MIA bracelets are part of VVMF’s The Wall That Heals exhibit, along with a Life magazine from 1972 featuring Valerie Kushner, whose husband was POW U.S. Army Harold Kushner. At the time of publication, more than 2,600men were missing or had been captured in Southeast Asia. Valerie Kushner worked diligently with others to bring attention to the POW/MIA families.

Callie Wright, VVMF’s Director of Education, talks to students at The Wall That Heals about POW/MIA bracelets, their significance, and who they honor.

Bricks from the Hanoi Hilton

On March 29, 2018 – also known as Vietnam Veterans Day – there was a ceremonial presentation of bricks from the Hanoi Hilton at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. The Hoa Lò Prison, also dubbed the Hanoi Hilton, was a prison camp where American POWs were held in North Vietnam. The bricks were presented to the Medal of Honor Society, the Vietnam Veterans of America (VVA), and the National Park Service.

Dozens of bricks were recovered in 1993 when an American official, driving to work in Hanoi, discovered the prison was being torn down. These bricks were entrusted to a group of USAF linguists called the “Doggers.” The Hoa Lò Prison complex has since been mostly demolished and has been converted into a museum.

The Hanoi Hilton bricks were given with a plaque that said, “This common construction brick was recovered in 1993 from the infamous Hoa Lo prison in North Vietnam, known to U.S. prisoners of war as the Hanoi Hilton. This brick relic is symbolic of the service and sacrifice of the millions of American veterans who answered their country’s call to duty during the Vietnam War.”

One of the bricks is a part of VVMF’s The Wall That Heals exhibit that travels to communities across the country.

The Cadet and the Goat

Of the more than 58,000 names on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, approximately 1,500 are still listed as Missing in Action. One of those names is Morgan Donahue, on Panel West 36, Line 14.

The son of a World War II Army aviator, Donahue was destined to serve in the military from an early age. Growing up on military bases throughout his childhood, he had a penchant for pranks. While a cadet at the Air Force Academy, he and his roommate John Albright – listed just above on Line 13 – became fast friends and were known for their hijinks. Their penultimate achievement was the kidnapping of the Naval Academy goat prior to the Air Force/Navy football game and parading it onto the field.

Following graduation from the Academy, Albright and Donahue were flying aboard a C-123 over the Ho Chi Minh trail on December 13, 1968. While providing illumination for accompanying bombers, they were involved in a mid-air collision. As their plane fell to the ground, it is believed both were able to escape. After search and rescue efforts returned only the pilot, they were listed as Missing in Action. You can see the cross symbol next to the names of Albright and Donahue – indicating their current status as Missing in Action.

Rolling Thunder

Rolling Thunder Washington, DC Inc., and its mission began as a demonstration following the era of the Vietnam War, which was a difficult time in our history. Many of America’s military were killed or missing in action (MIA) and their remains were not being returned home or respectfully buried. There were also reports of live prisoners of war (POW) who were left behind when the war ended.

In 1987, Vietnam veteran Ray Manzo (CPL, USMC), bothered by these accounts, came to DC with his idea and met and enlisted the help of fellow veterans to organize a motorcycle demonstration to bring attention to the POW/MIA situation. Choosing Memorial Day weekend for the event, they envisioned the arrival of the motorcycles coming across the Memorial Bridge, and thought it would sound like “Rolling Thunder”. The first Run in 1988, had roughly 2500 motorcycles and riders demanding that the U.S. government account for all POW/MIA’s. It continues to grow every year, becoming the world’s largest single-day motorcycle event. Now with over a million riders and spectators combined, Rolling Thunder has evolved into an emotional display of patriotism and respect for all who defend our country.

The event is an actual demonstration/protest to bring awareness and accountability for POWs and MIAs left behind.

Rolling Thunder Washington, DC, Inc’s mission is to educate, facilitate, and never forget by means of a demonstration for service members that were abandoned after the Vietnam War. The Rolling Thunder First Amendment Demonstration Run has also evolved into a display of patriotism and respect for all who defend our country.

The POW / MIA Bracelet

The following historical information was written by Carol Bates Brown, one of the originators:

I was the National Chairman of the POW/MIA Bracelet Campaign for VIVA (Voices In Vital America), the Los Angeles based student organization that produced and distributed the bracelets during the Vietnam War. Entertainers Bob Hope and Martha Raye served with me as honorary co-chairmen.

The idea for the bracelets was started by a fellow college student, Kay Hunter, and me, as a way to remember American prisoners of war suffering in captivity in Southeast Asia. In late 1969, television personality Bob Dornan (who several years later was elected to the US Congress) introduced us and several other members of VIVA to three wives of missing pilots. They thought our student group could assist them in drawing public attention to the prisoners and missing in Vietnam. The idea of circulating petitions and letters to Hanoi demanding humane treatment for the POWs was appealing, as we were looking for ways college students could become involved in positive programs to support US soldiers without becoming embroiled in the controversy of the war itself. The relatives of the men were beginning to organize locally, but the National League of POW/MIA Families had yet to be formed.

During that time, Bob Dornan wore a bracelet he had obtained in Vietnam from hill tribesmen, which he said always reminded him of the suffering the war had brought to so many. We wanted to get similar bracelets to wear to remember US POWs, so rather naively, we tried to figure out a way to go to Vietnam. Since no one wanted to fund two sorority-girl types on a tour to Vietnam during the height of the war, and our parents were livid at the idea, we gave up and Kay Hunter began to check out ways to make bracelets. Soon other activities drew her attention and she dropped out of VIVA, leaving me, another student Steve Frank, and our adult advisor, Gloria Coppin, to pursue the POW/MIA awareness program.

The major problem was that VIVA had no money to make bracelets, although our advisor was able to find a small shop in Santa Monica that did engraving on silver used to decorate horses. The owner agreed to make 10 sample bracelets. I can remember us sitting around in Gloria Coppin’s kitchen with the engraver on the telephone, as we tried to figure out what we would put on the bracelets. This is why they carried only name, rank and date of loss, since we didn’t have time to think of anything else.

Armed with sample bracelets, we set out to find someone who would donate money to make bracelets for distribution to college students. It had not yet occurred to us that adults would want to wear them, as they weren’t very attractive. Several approaches to Ross Perot were rebuffed, including a proposal that he loan us $10,000 at 10% interest. We even visited Howard Hughes’ senior aides in Las Vegas. They were sympathetic but not willing to help fund our project. Finally in late summer of 1970, Gloria Coppin’s husband donated enough brass and copper to make 1,200 bracelets. The Santa Monica engraver agreed to make them and we could pay him from any proceeds we might realize.

Although the initial bracelets were going to cost about 75 cents to make, we were unsure about how much we should ask people to donate to receive a bracelet. In 1970, a student admission to the local movie theater was $2.50. We decided this seemed like a fair price to ask from a student for one of the nickel-plated bracelets. We also made copper ones for adults who believed they helped their “tennis elbow”. Again, according to our logic, adults could pay more, so we would request $3.00 for the copper bracelets.

At the suggestion of local POW/MIA relatives, we attended the National League of Families annual meeting in Washington, DC in late September. We were amazed at the interest from the wives and parents in having their man’s name put on bracelets and in obtaining them for distribution. Bob Dornan, who was always a champion of the POW/MIAs and their families, continued to publicize the issue on his Los Angeles television talk show and promoted the bracelets.

On Veterans Day, November 11, 1970, we officially kicked off the bracelet program with a news conference at the Universal Sheraton Hotel. Public response quickly grew and we eventually got to the point we were receiving over 12,000 requests a day. This also brought money in to pay for brochures, bumper stickers, buttons, advertising and whatever else we could do to publicize the POW/MIA issue. We formed a close alliance with the relatives of missing men – they got bracelets from us on consignment and could keep some of the money they raised to fund their local organizations. We also tried to furnish these groups with all the stickers and other literature they could give away.

While Steve Frank and I ended up dropping out of college to work for VIVA full time to administer the bracelet and other POW/MIA programs, none of us got rich off the bracelets. VIVA’s adult advisory group, headed by Gloria Coppin, was adamant that we would not have a highly paid professional staff. As I recall the highest salary was $15,000 a year and we were able to keep administrative costs to less than 20 percent of income.

In all, VIVA distributed nearly five million bracelets and raised enough money to produce untold millions of bumper stickers, buttons, brochures, matchbooks, newspaper ads, etc., to draw attention to the missing men. In 1976, VIVA closed its doors. By then the American public was tired of hearing about Vietnam and showed no interest in the POW/MIA issue.

Information courtesy of the National League of POW/MIA Families

Echoes of the Vietnam War Podcast

EP04 – A Bump in the Road

Hal Kushner was a U.S. Army flight surgeon from 1967 to 1977, and spent more than half of that time as a prisoner of war in Vietnam. In this episode, Dr. Kushner recalls his experiences before, during, and after his imprisonment. Also, we remember “the Mayaguez incident.”

https://echoes-of-the-vietnam-war.simplecast.com/episodes/a-bump-in-the-road

EPISODE SHOW NOTES

- The Mayaguez Incident – https://dpaa-mil.sites.crmforce.mil/dpaaFamWebInMayaguez

- Day Uy Bac Si, Captain Doctor book – https://www.amazon.com/Dai-Bac-Captain-Doctor-Physician/dp/0972132619

- The Wall of Faces: Karl Edmond Shenep – https://www.vvmf.org/Wall-of-Faces/47075/KARL-E-SHENEP/

- The Wall of Faces: Stephen Richard Porcella – https://www.vvmf.org/Wall-of-Faces/41302/STEPHEN-R-PORCELLA/

- The Wall of Faces: Griffith Bronson Bedworth – https://www.vvmf.org/Wall-of-Faces/3231/GRIFFITH-B-BEDWORTH/

- The Wall of Faces: Kenneth Dale McKee – https://www.vvmf.org/Wall-of-Faces/36885/KENNETH-D-MCKEE/

- Theodore Wilson Guy – https://valor.militarytimes.com/hero/3581

- The Wall That Heals – https://www.vvmf.org/The-Wall-That-Heals/

- Full Interview with Hal Kushner – https://youtu.be/iH-TphGZfIg

- YouTube Echoes of the Vietnam War Interview playlist – https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLK63b6Cn53unMMj-yZYEch0RuYy1YN1zl

EP13 – Missing in Action

More than 1,500 Americans from the Vietnam War remain unaccounted for. In this episode, one woman whose father is still MIA tells about her journey from silence to advocacy. Another explains why she rode her bicycle 1,200 miles through the jungles of southeast Asia in search of her father’s crash site.

https://echoes-of-the-vietnam-war.simplecast.com/episodes/missing-in-action

EPISODE SHOW NOTES

- VVMF Topic Page on POW/MIA – https://www.vvmf.org/topics/POWMIA/

- Wall of Faces: Kenneth A Stonebraker – https://www.vvmf.org/Wall-of-Faces/50123/KENNETH-A-STONEBRAKER/

- Wall of Faces: Stephen A Rusch – https://www.vvmf.org/Wall-of-Faces/44905/STEPHEN-A-RUSCH/

- Wall of Faces: Carter A Howell (co-pilot with Stephen) – https://www.vvmf.org/Wall-of-Faces/24364/CARTER-A-HOWELL/

- POW/MIA League of Families – https://www.pow-miafamilies.org/status-of-the-issue.html

- DPAA Website – https://www.dpaa.mil/

- Woody Williams Foundation – https://woodywilliams.org/

- Blood Road – https://www.amazon.com/Blood-Road-Rebecca-Rusch/dp/B0721YYH3Z

- Rebecca Rusch: Be Good Foundation – https://www.rebeccarusch.com/be-good-foundation

- Article22 – https://article22.com/

- Full Interview with Cindy Stonebraker – https://youtu.be/FcACRpNT3ss

- Full Interview with Rebecca Rusch – https://youtu.be/klNErV2yZhk

- The Wall That Heals – https://www.vvmf.org/The-Wall-That-Heals/

- YouTube Echoes of the Vietnam War Interview playlist – https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLK63b6Cn53unMMj-yZYEch0RuYy1YN1zl

EP52 – Unwavering

There are more than 72,000 U.S. service members still unaccounted for from World War II — a war we fought in for four years. The number missing after 20 years of combat in Afghanistan? Zero. That’s no accident; it represents a dramatic shift in policy and priorities, another unheralded legacy of the Vietnam War generation. In this episode, author Taylor Baldwin Kiland shares the incredible true story of the military wives who fought to make “no man left behind” a promise that America keeps.

https://echoes-of-the-vietnam-war.simplecast.com/episodes/unwavering

EP103: The Fullest Possible Accounting (Part One)

September 19, 2025 is National POW/MIA Recognition Day in the United States. In this two-part series, we’ll explore what it means to be part of that ongoing story — the families who wait, the system created to find answers, and the private researchers who work to complement the government’s efforts.

Additional Resources

Websites

National League of POW/MIA Families

Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA)

National POW/MIA Memorial & Museum

Videos

2/12/1973: First POWs Return From Vietnam: ABC News

HOMECOMING Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, Vietnam, AND Clark AB, Philippine Islands, 14-19 March 1973: U.S. National Archives | YouTube

Interview with Mary Hoff, designer of the POW/MIA Flag: National POW/MIA Memorial & Museum | YouTube

U.S. Veteran Describes Being Prisoner of War in Vietnam: Iowa PBS | YouTube

Vietnam War POW talks about his 7 years in Hanoi Hilton: Iowa Veterans’ Perspective | YouTube

Vietnam POW Escape | No Man Left Behind: National Geographic | YouTube

Vietnam War Ended 40 Years Ago But Lives On For MIA Families: KPBS | YouTube

Never Forgotten: Recovery mission in Vietnam: U.S. Army | YouTube

News Stories

Prisoners of War during Vietnam: Pritzker Military Museum & Library

Operation HOMECOMING: Repatriation of American prisoners of war in Vietnam described: U.S. Army

The M.I.A Issue: PBS | The American Experience

Blogs

A Hero’s Welcome: How a pilot missing for 52 years came home: VVMF

A Life Cut Short: 50 years after Navy pilot disappeared, loved ones hope for answers: VVMF

Remembering Marine veteran whose 30-year career ended as a POW in Vietnam: VVMF

Legacy of Lt. Col. Anthony Shine: Air Force award given in honor of fallen pilot: VVMF

Daughter longs for closure 49 years after father went missing in action: VVMF