The U.S. military first employed combat helicopters in WWII, to extract downed flight crews. The Korean War saw an increased role for helicopters, most notably in medical evacuations. But “choppers” truly came of age as tactical fighting machines during the Vietnam War — in fact, Vietnam is often referred to as “the helicopter war.”

Overview

Moving troops from one place to another is a logistical imperative of combat — the most prepared fighters with the most advanced weapons are ineffective if they can’t get to the fight. Because Vietnam lacked a developed network of roads, its jungles and mountains were particularly difficult to access. Helicopters could move service members and supplies quickly, even to remote locations.

The helicopter’s potential in combat was not so much determined as it was discovered. “For most of the war, there was no formal Army training to prepare scout pilots and observers,” writes Donald Porter in Air & Space. “Army headquarters developed doctrine by building on what worked in the field, rather than the other way around, and each unit in-country did things slightly differently.”

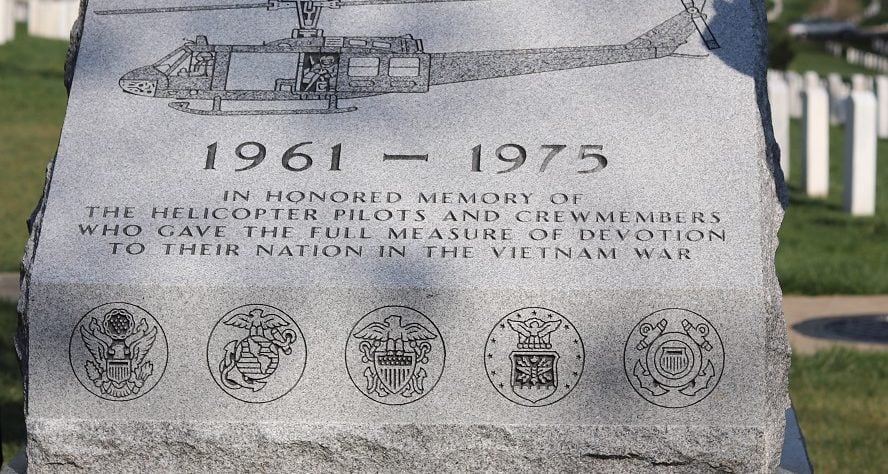

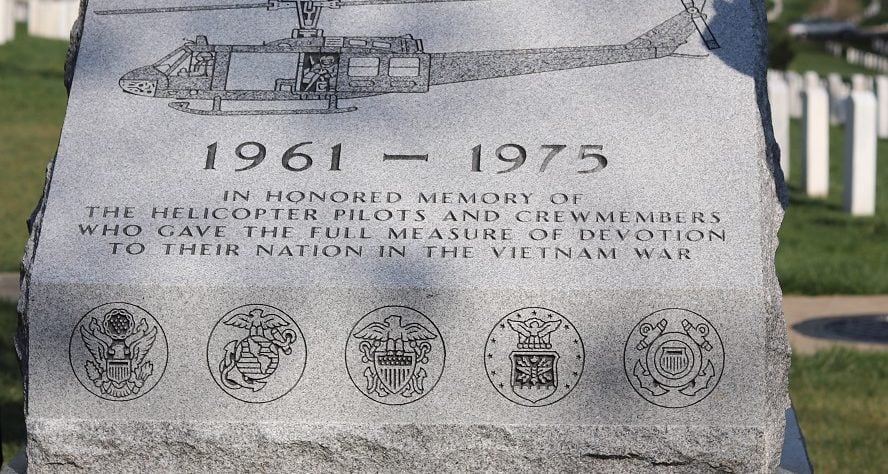

All branches of the military used helicopters in Vietnam, for a range of purposes — movement of troops and supplies, medical evacuations (commonly called “Dustoff” missions), scouting, and providing air support for troops on the ground. The variety of roles bred a variety of helicopters, the most famous being the Army’s UH-1 “Iroquois” (widely known as the “Huey”), which logged more than 10 million flight hours in Vietnam and is pictured on the Vietnam Helicopter Pilot and Crewmember Monument in Arlington National Cemetery. The “Huey” remains one of the most recognized symbols of the conflict.

Overall, the U.S. military used nearly 12,000 helicopters in Vietnam, of which more than 5,000 were destroyed. To be a helicopter pilot or crew member was among the most dangerous jobs in the war.

With the Vietnam War came major advances in medical care, some of which continue to be used as standard practice in civilian medical care today. Perhaps the most significant innovation in medical care of the Vietnam War was the widespread use of air ambulances for helicopter evacuation—also known as medevacs. The Bell UH-1 helicopter reduced the amount of time from wounding to treatment to an average of 35 minutes, a monumental decrease as compared to the 4-6 hours from wounding to treatment for the evacuated in Korea. There were a total of 116 helicopter ambulances operating in Vietnam by 1968, and after state authorities in the US began following suit in using helicopters to transport highway crash victims, the practice became the norm—many hospitals in the US have helicopter landing pads for this purpose.

Innovations in the transportation of the injured have also impacted the level and immediacy of care for wounded soldiers. The use of medevacs in Vietnam was revolutionary in the 1960’s; the use of “Flying ICUs” is considered a remarkable advance in the context of today’s military conflicts. Flying ICUs (intensive care units), are Air Force planes which have permanently installed ICU devices and a range of skilled medical professionals able to provide the highest level of care within minutes of wounding. While many advancements in medical care were introduced at a wide scale in Vietnam, military medical care continues to advance today and influence medical care in your own local hospitals.

Nearly 5,000 helicopter pilots and crewmembers lost their lives conducting aerial operations in Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War. On April 18, 2018, the Vietnam Helicopter Pilot and Crewmember Monument was dedicated at Arlington National Cemetery.

Vietnam has been called America’s “Helicopter War” because helicopters provided mobility throughout the war zone, facilitating rapid troop transport, close air support, resupply, medical evacuation, reconnaissance, and search and rescue capabilities. The Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association (VHPA) spearheaded the effort for the Vietnam Helicopter Pilot and Crewmember Monument at Arlington National Cemetery. They estimate that over 100,000 helicopter pilots and crew members served during the Vietnam War. Helicopters were used in more than 850,000 medical evacuation missions and were responsible for boosting survival rates for the wounded.

The Vietnam Helicopters Memorial Tree was dedicated in 2015 and honors the helicopter pilots and crew members who died while serving in Southeast Asia from 1961 to 1975. More than 300 helicopter pilots and crewmembers are buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Bruce Crandall

The Battle of Ia Drang was the first major engagement during the Vietnam War, between members of the U.S. Army and the People’s Army of North Vietnam.

The Battle of Ia Drang was the first major engagement during the Vietnam War, between members of the U.S. Army and the People’s Army of North Vietnam.

The two-part battle took place between November 14 and November 18, 1965 west of Plei Me, in the Central Highlands of South Vietnam. Lt. Col. Hal Moore’s 1st Battalion, 7th Calvary was ordered to take on an air assault in the Ia Drang Valley. Their mission was to find and kill the enemy. At approximately noon, the North Vietnamese 33rd Regiment attacked. The fighting continued all day and into the night.

Col. Bruce Crandall, Commander of Company A, 229th Assault Helicopter Battalion, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), led the first major division operation of airmobile troops into Landing Zone X-Ray.

After several routine lifts into the area, the men on the ground came under attack from the North Vietnamese Army. On his next flight, three soldiers on his helicopter were killed and three were wounded. Crandall kept his helicopter on the ground – in the line of enemy fire, so that four wounded soldiers could be loaded aboard. After he flew the men back to base, he knew the soldiers on the ground were running short of ammunition, so he decided to fly back in. He asked for a volunteer to go with him and Captain Ed Freeman agreed to pursue it with him, displaying extraordinary heroism. Together, they flew in supplies, water, and ammunition needed for the troops. His helicopter came under intense enemy fire, but they continued to carry out the wounded, even though that wasn’t their mission.

Crandall continued to fly into and out of the landing zone throughout the day and into the evening. Throughout the day, he changed helicopters after some were so badly damaged to stay in the air. He spent more than 14 hours in the air and completed a total of 22 flights, most under intense enemy fire. He retired from the battlefield only after all possible service had been rendered to the infantry battalion. Crandall and Freeman successfully rescued some 70 wounded men.

.

“It was the longest day I ever experienced in any aircraft,” Crandall recalled. “The Huey was the best helicopter ever made. We saved so many more people because of that helicopter.”

On February 26, 2007, President George W. Bush presented Crandall with the Medal of Honor for his actions in the Ia Drang Valley.

U.S. Air Force A1C William ‘Pits’ Pitsenbarger was an Air Force pararescue medic who completed more than 300 missions in Vietnam. He was 21 years old when he lost his life, but he is remembered for how honorably and selflessly he lived.

On April 11, 1966, a call came to help 134 men of Charlie Company, 2nd Battalion, 16th Infantry, 1st Infantry Division. The soldiers were surrounded by a battalion of Viet Cong troops near Cam My, Vietnam. The company was pinned down and casualties were mounting. Pits joined the rescue efforts after Detachment 6 of the USAF’s 38th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron received a call to help evacuate the wounded.

Pits volunteered to be lowered down to hoist the wounded, where they would then be sent to a nearby airfield. He helped organize the rescue efforts and was able to pull out nine soldiers. When Pits had the option to leave with the helicopter, he elected to stay and care for the wounded and dying – all while under fire. The fighting grew intense and went into the night. He gathered weapons and ammunition from the dead, and continued to look after the wounded until he was killed. Charlie Company suffered a devastating 80% casualties.

For his actions, Pits was posthumously awarded the Air Force Cross. It wasn’t until surviving comrades and eyewitnesses put in requests and testimonies for an upgrade, that it was granted. It took 34 years before the Medal of Honor recommendation came to fruition – and his parents accepted the award on his behalf on Dec. 8, 2000.

Medal of Honor Citation: Airman First Class Pitsenbarger distinguished himself by extreme valor on 11 April 1966 near Cam My, Republic of Vietnam, while assigned as a Pararescue Crew Member, Detachment 6, 38th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron. On that date, Airman Pitsenbarger was aboard a rescue helicopter responding to a call for evacuation of casualties incurred in an ongoing firefight between elements of the United States Army’s 1st Infantry Division and a sizeable enemy force approximately 35 miles east of Saigon. With complete disregard for personal safety, Airman Pitsenbarger volunteered to ride a hoist more than one hundred feet through the jungle, to the ground. On the ground, he organized and coordinated rescue efforts, cared for the wounded, prepared casualties for evacuation, and insured that the recovery operation continued in a smooth and orderly fashion. Through his personal efforts, the evacuation of the wounded was greatly expedited. As each of the nine casualties evacuated that day was recovered, Airman Pitsenbarger refused evacuation in order to get more wounded soldiers to safety. After several pick-ups, one of the two rescue helicopters involved in the evacuation was struck by heavy enemy ground fire and was forced to leave the scene for an emergency landing. Airman Pitsenbarger stayed behind on the ground to perform medical duties. Shortly thereafter, the area came under sniper and mortar fire. During a subsequent attempt to evacuate the site, American forces came under heavy assault by a large Viet Cong force. When the enemy launched the assault, the evacuation was called off and Airman Pitsenbarger took up arms with the besieged infantrymen. He courageously resisted the enemy, braving intense gunfire to gather and distribute vital ammunition to American defenders. As the battle raged on, he repeatedly exposed himself to enemy fire to care for the wounded, pull them out of the line of fire, and return fire whenever he could, during which time he was wounded three times. Despite his wounds, he valiantly fought on, simultaneously treating as many wounded as possible. In the vicious fighting that followed, the American forces suffered 80 percent casualties as their perimeter was breached, and Airman Pitsenbarger was fatally wounded. Airman Pitsenbarger exposed himself to almost certain death by staying on the ground, and perished while saving the lives of wounded infantrymen.

His story is also told in the film, “The Last Full Measure.”

The name of William Pitsenbarger is inscribed on Panel 6E, Line 102 of The Wall.

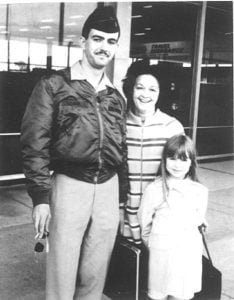

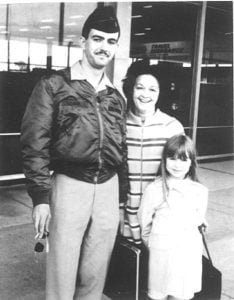

David Kink

Kink had been in Vietnam one month when he was involved in a helicopter crash that would result in his death. At the time of the crash, he had logged about 66 hours of combat pilot time, mostly in Hueys.

On July 21, 1969, Kink was co-pilot in a light observation helicopter flying at a low altitude searching for signs that the ground had been disturbed by the enemy. A Cobra gunship fired at a target and detonated a U.S. bomb hidden on the ground. The blast slammed into Kink’s helicopter, killing the pilot and another crew member. Kink crawled away from the burning wreck with burns and broken bones. He was evacuated to a Japanese hospital where he died less than two weeks later.

In his last letter home, he wrote, “I’ve only seen one aviator killed since I’ve been here. You see, you’re never alone on a mission. There’s always somebody to protect you and get you out even before you hit the ground… ‘”

David is buried at Sunset Memory Gardens in Madison, Wisconsin. His name is remembered on Panel 20W, Line 92 of The Wall.

In 2011, she wrote, “I still don’t remember my brother’s voice . . . how long his fingers were . . . how his flight jacket felt. But I’ve learned about my brother and his service in Vietnam by finding his fellow aviators . . . the pilots who shared his last mission, and the families of those who also died. Today, I know not only how David died, but more importantly, how he lived. ”

Julie was involved in the national effort to establish a Helicopter Pilot and Crewmember Monument and gave remarks at its dedication in 2015. She remains committed to honoring David’s legacy. Listen to her talk about David at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in 2017.

Julie was a guest on VVMF’s Podcast, Echoes of the Vietnam War, in April 2021. She shares her story in Episode 2: “The Sound of Hope”. Hear her full interview below.

![CF010508-Edit[1]](https://www.vvmf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/CF010508-Edit1-975x474.jpg)

![CF010508-Edit[1]](https://www.vvmf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/CF010508-Edit1-975x474.jpg)

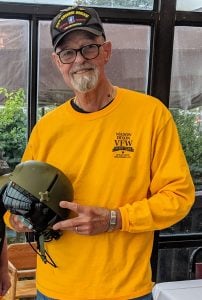

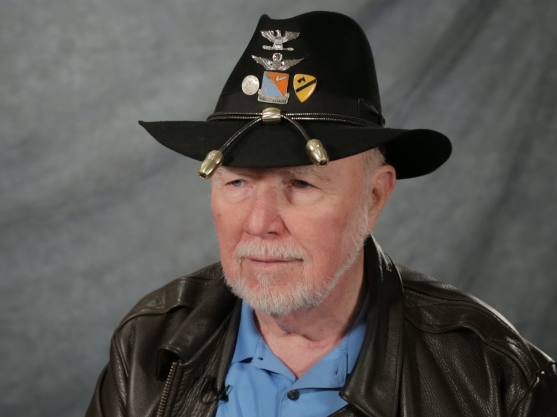

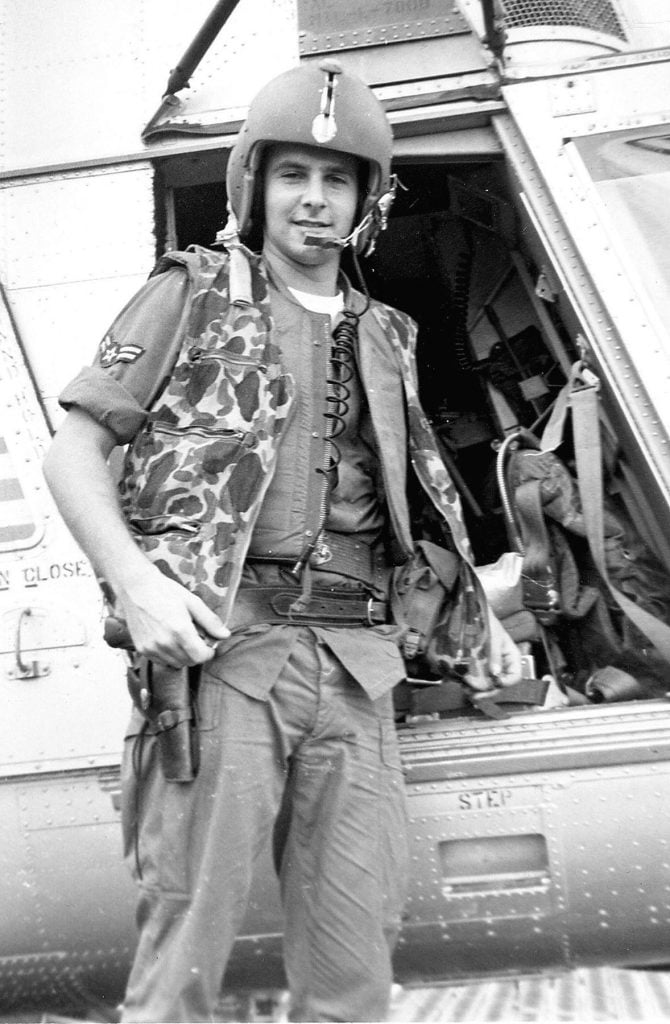

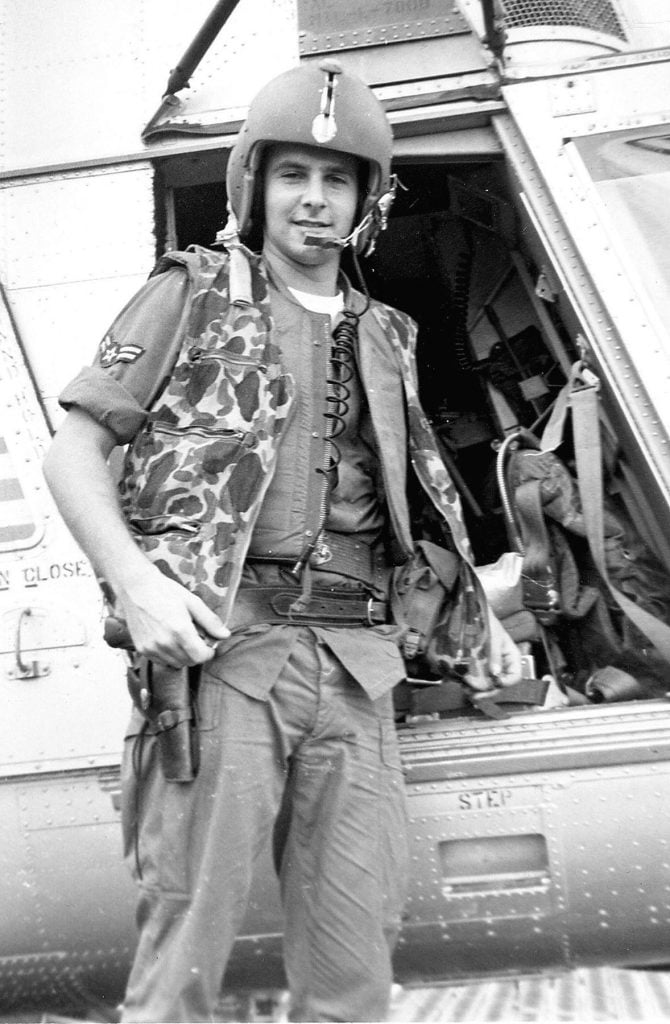

Retired U.S. Army COL Richard “Rich” Kuhblank served in Vietnam from 1966-1967 with the 335th Assault Helicopter Company, 173rd Airborne Brigade and from again from 1968 -1969 with the 1st Aviation Battalion, 1st Infantry Division. He was a helicopter pilot who later became responsible for teaching other pilots how to investigate crash sites.

Rich’s flight helmet is one of the artifacts you’ll find in VVMF’s mobile exhibit, The Wall That Heals. He donated it while visiting The Wall That Heals in Ocean View, Maryland in 2019.

You can hear Rich’s remarkable story about life as a helicopter pilot in Episode 2 of the Echoes of the Vietnam War Podcast: “The Sound of Hope”.

EP2 – The Sound of Hope

In this episode, we hear two personal stories related to the use of helicopters in Vietnam. Rich Kuhblank was a helicopter pilot during the war, and later became responsible for teaching other pilots how to investigate crash sites. Julie Kink lost her brother, David, whose helicopter was shot down when she was only eight years old. Decades later, she found an entire community of new “big brothers” when she set out to learn more about David’s life in the army.

EPISODE SHOW NOTES

- VVMF Topic Page on Helicopters – https://www.vvmf.org/topics/Helicopters/

- Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association – https://www.vhpa.org/

- The Wall of Faces: John Ernest Anderson, co-pilot of David’s – https://www.vvmf.org/Wall-of-Faces/1032/JOHN-E-ANDERSON/

- The Wall of Faces: Edward Michael Dennull, gunner in David’s helicopter – https://www.vvmf.org/Wall-of-Faces/12979/EDWARD-M-DENNULL/

- The Wall of Faces: David Robert Kink, Julie’s brother – https://www.vvmf.org/Wall-of-Faces/28091/DAVID-R-KINK/

- Luther Russel – https://www.vhpa.org/DAT/datR/D06405.HTM

- The Wall That Heals – https://www.vvmf.org/The-Wall-That-Heals/

- YouTube Echoes of the Vietnam War Interview playlist – https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLK63b6Cn53unMMj-yZYEch0RuYy1YN1zl

Podcasts

Echoes of the Vietnam War Episode 2: “The Sound of Hope”

Blogs

A Dustoff Medic Remembers Written by Neal Stanley

“He completed a total of 22 flights”: Rescuing Wounded In the Ia Drang Valley

‘I Feel Closer to My Brother’: Families of Fallen Helicopter Pilots Unite with Veterans to Heal

Helicopters in Vietnam

- VIDEO: Helicopter Warfare in the Vietnam War | US Army Documentary

- The U.S. Army 1st Cavalry Division in Vietnam

- The Scout Helicopter Pilot: A Different Breed

Pilots and Crew Members

- Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association

- Vietnam Helicopter Crew Members Association

- VIDEO: Helicopter Training at Fort Wolters

- VIDEO: Vietnam War Helicopter Pilot

- VIDEO: Shotgun Rider: Helicopter Door Gunners in the Vietnam War

AH-1 Cobra

- The AH-1 Cobra Gunship in Vietnam

- Cobra Attack Helicopter

- S. Marine’s Bell AH-1 Sea Cobra Attack Helicopter Combat Capabilities

UH-1 Huey