Thank you to the following reviewers of the curriculum: Andrew Demko, Rainier Junior/Senior High School; George Herring, University of Kentucky; Mark Lawrence, University of Texas at Austin; Ed Moise, Clemson University; Susan Tomlinson, Franklin Central High School.

Teachers/Presenters:

Download Presentation – requires internet connection

Download Presentation – does not require internet connection

ABOUT THE EVOLUTION OF THE DRAFT

Do you think a draft system is needed in this country? Why or why not? Some form of conscription, or draft, has existed in the US at many points since the nation’s founding, though it has changed in nature over time.

During the Civil War, riots erupted in New York in response to a draft that was enacted in the Union in 1863 (see slide 1). Eligible men aged 25 to 45 were compelled to serve unless they could pay $300 for a substitute. A similar law had been enacted in the South the previous year, in 1862. Much of the opposition to the draft in the Union was closely related to the perception of status and power of working class white Americans (particularly Irish immigrants) in relation to the status of black Americans, who were exempt from service because they were not considered citizens but (in the white perspective) enjoyed some of the same freedoms as citizens in the Union. There were over 1000 deaths in the riots, and one consequence was the 1865 amendment to the Enrollment Act, which punished draft evasion with loss of citizenship.

In 1917, Congress passed the Selective Service Act, which required all men aged 20-30 to register for military service, with no possibility for a paid substitute (see slide 2). This marked the first national effort to get individuals registered for times of national emergency. About 10 million men registered, and by 1918 over 2 million men had been inducted by the local lottery system (see slide 3). It is estimated that at least 2 million men staged acts of civil disobedience by refusing to register. With the rise of public dissent against the war and against the draft, Congress passed the Sedition Act of 1918, which made it illegal to “willfully utter, print, write, or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of the Government of the United States” or to “willfully urge, incite, or advocate any curtailment of the production” of the things “necessary or essential to the prosecution of the war.” Observe George Bellows’ 1917 cartoon “Blessed Are the Peacemakers,” shown in slide 4. What details do you notice about the man depicted? In light of the Sedition Act, do you think the drawing and publication of this cartoon can be classified as civil disobedience? What can you infer about the state of free speech from this cartoon?

The outbreak of World War II in Europe and the Far East gave rise to the first ever peacetime conscription in the US with the passage of the Selective Training and Services Act of 1940. This act increased the range of ages for registration to any male between 21 and 35. Those who were drafted by local draft boards would be required to serve for one year somewhere in the Western hemisphere. In 1941 following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the age was lowered to 18, and location of service was changed to anywhere required. Official provisions were made for those who identified as conscientious objectors– they could be permitted to perform alternative national service in place of military service if drafted. Much of the public dissent against the war came from conscientious objectors, such as those depicted protesting conscription in 1941 in New York in slide 5.

Examine the image on slide 6. What is happening in this scene? Students from the University of Washington are burning their draft cards, which are notices sent by the government indicating that a person had been registered with the Selective Service System, and indicated that person’s status in the system. Leading up to and during the Vietnam War, the draft evolved in how individuals could “defer” their service; in the way the draft system worked; and in the growth of popular resistance against a draft system. First, there were several ways in which an individual could receive a deferment of service with changes to draft classifications introduced in 1962, including: being a college student; being a student at a divinity school, or being a clergy leader; having dependent children; being the sole supporter of a parent; various forms of medical exemptions.

Watch the video of the nationally televised draft lottery drawing included on slide 7. On November 26, 1969 President Nixon signed an amendment to the Military Selective Service Act of 1967 that established conscription based on random selection (lottery). Opposition to the draft during Vietnam was widespread, with some personally opposed to forced military service, some opposed to the war as a whole as illegitimate and immoral, and some opposed to the system of deferments which led to a disproportionately working class force in Vietnam— as many as three quarters of those who served in Vietnam were from either working or lower class families. In 1971, student deferments were ended, and draft boards (who would review other types of deferments which were still allowed) were compelled to revise their makeup if necessary to better reflect the communities they represented. These changes sought to make the process and priorities for induction more transparent and fair by creating a process of random selection, as opposed to the (some would argue) subjective processes of selection that would occur within local draft boards.

Between 1964 and 1973, nearly two million men were drafted. In 1973, in large part due to public opinion, the draft officially ended and, with the support of President Nixon, an all-volunteer military force was established. Read the excerpt from the Gates Commission report on the establishment of an all-volunteer force that is included on slide 8. Can you point out where opposition to the draft and the anti-war movement of the Vietnam era is subtly referenced in the text?

The all-volunteer force continues today, which has led to significant differences in the composition of the military as compared to American society. For example, recruits today come primarily from the middle and lower classes, with the distribution not reflecting that of the greater American society. Many who choose to enlist cite stable pay, medical benefits, and the possibility of advancement as motivations for joining the military. These are benefits that the military uses in its recruitment efforts (see slide 9). Regardless, opposition to the all-volunteer force exists, for various reasons, from both the general public and the military community. Watch the clip included on slide 10 of a conversation with former Secretary of State Colin Powell and journalist Jim Lehrer, starting at the 2:40 minute mark and ending at the 4:10 minute mark. What are some of the reservations Powell expresses about the all-volunteer force? What are the obstacles to the reinstating of a draft system?

Regardless of public opinion regarding the draft, one of the lessons of Vietnam that has persisted is the need to separate war and warrior—those who serve, whether called or enlisted, should be recognized for their service.

Former curator of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Collection Duery Felton discusses a selective service, or draft, card.

Thank you to the following reviewers of the curriculum: Andrew Demko, Rainier Junior/Senior High School; George Herring, University of Kentucky; Mark Lawrence, University of Texas at Austin; Susan Tomlinson, Franklin Central High School.

Teachers/Presenters:

Download Presentation – requires internet connection

Download Presentation – does not require internet connection

ABOUT PROTESTS AGAINST THE WAR

What are some different reasons a person might oppose a war? The reasons might involve questions of the legality or morality of the war in question or of war in general, or reasons for opposition might be more personal.

During the Civil War, riots broke out in New York in response to a draft that was enacted in the Union in 1863. Eligible men aged 25 to 45 were compelled to serve unless they could pay $300 for a substitute. Much of the opposition expressed by the public was in response to the draft, and the opposition to the draft was closely related to the perception of status and power of working class white Americans (particularly Irish immigrants) in relation to the status of black Americans, who were exempt from service because they were not considered citizens but enjoyed some of the same freedoms as citizens in the Union.

During World War I, opponents of U.S. involvement focused on the inequities of the draft but also demanded protection of free speech, especially after the enactment of the Sedition and Espionage Acts. The Sedition Act of 1918 made it illegal to “willfully utter, print, write, or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of the Government of the United States” or to “willfully urge, incite, or advocate any curtailment of the production” of the things “necessary or essential to the prosecution of the war.” Eugene Debs, pictured in slide 1, was a union leader and presidential candidate under the Socialist Party of America, who in 1918 delivered a speech in Canton, Ohio, that led to his arrest and imprisonment under the terms of the Sedition and Espionage Acts. Read the excerpt of Debs’ speech included on slide 2. Do you agree or disagree with Debs’ ideas about the nature of war? Do you think his words have relevance in the 21st century? Slides 3 and 4 show some popular opposition to the Sedition Act, which many viewed as unconstitutional—and it was repealed two years later in 1920.

Prior to and during World War II, opposition to the war also took the form of isolationism and non-interventionism, the idea that the U.S. had no incentive or justification to participate in a foreign war, because U.S. security was not directly threatened (see slide 5). One of the main organizations leading this anti-war movement was the America First Committee (formed in 1940), which advocated that American democracy would be weakened by participation in a European war. Take a look at the poster included on slide 6. What message do you think this poster is trying to communicate?

Play the video of Charles Lindbergh’s address to the nation on behalf of the America First Committee that is included on slide 7. What is Lindbergh questioning or criticizing about arguments in support of U.S. involvement in the war? How would you describe Lindbergh’s tone?

Opposition to the war in Vietnam involved many of the same reasons that the American public had expressed in the past: a resistance to compulsory service via the draft; opposition to U.S. intervention in a foreign conflict; a right to free speech expressing disapproval for war as an immoral pursuit. There were also some reasons peculiar to Vietnam: doubts that the Vietnamese communists were properly understood as communists; fears that the United States could not achieve its goals in Vietnam at a reasonable cost; concerns that Vietnam was not important to US security interests to justify the cost of war. The face of the anti-war movement of Vietnam was young, just as it was for those who served- much of the public activism against the war was driven by college students, especially in the early phases of the conflict.

Students for a Democratic Society was a student activist group founded in 1962 that played a prominent role in the spread of campus-based anti-war activism, with over 450 chapters nationwide by 1966 (before splintering later). As with previous wars, some of the opposition to the Vietnam war expressed by SDS and others included a resistance to the draft (see slide 8). Resistance also involved an objection to what was seen as an exercise in U.S. imperialism (see slide 9)—a resistance to becoming involved in a foreign conflict that experts would characterize as a post-colonial struggle in nation building, rather than ” the simple fact that South Vietnam, a member of the free world family, is striving to preserve its independence from communist attack,” as stated in 1964 by then Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara.

A significant wartime change that came with Vietnam was the immediacy and arguably transparency of news coverage of the war. For the first time, American citizens were exposed to the grim realities of war, including coverage of war crimes such as the massacre of the civilians of My Lai by U.S. troops in 1968 (see slide 10 for the iconic news image). With exposure to incidents like these in the media, Americans grew increasingly disillusioned with the war (disapproval ratings reached 64% in 1970), and opposition to the war focused on the immorality and futility of U.S. operations in Vietnam. Americans could see that their government’s policy was not bringing results in either the military or political spheres. The war continued without an end in sight, and Americans began to question the government’s conduct of the conflict. Many called for an end to the conflict, whereas others demanded that the government escalate US involvement further in order to achieve the elusive victory.

Beginning in 1965 and onward through the duration of the war, university faculty and students around the nation responded to the increasing disapproval of the war by hosting “teach-ins,” which involved multi-day seminars on various topics relating to the war’s legality and morality (see slide 11). The teach-ins represented a non-violent means of voicing disapproval and organizing for action.

Perhaps the peak of the anti-war movement was seen in the shootings at Kent State University in May 1970 (see slide 12). Students at Kent State had organized to protest the US and South Vietnamese invasion into Cambodia that had been recently authorized and announced to the public by President Nixon. The protest led to the deaths of four students at the hands of the National Guard, and marked increasing public tensions regarding the war.

In 1971, the Vietnam Veterans Against the War, an organization of returned veterans who opposed the war for various reasons, organized what is known as Operation Dewey Canyon III (see slide 13). This involved a march to the Capitol in Washington, DC, where hundreds of veterans threw their medals earned in war over the Capitol fence, in a symbolic act of opposition to the war. Later on, VVAW member (now Secretary of State) John Kerry testified against the war before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Read the excerpt of Kerry’s testimony included on slide 14. What do Kerry and VVAW cite as reasons to oppose the war?

The legacy of the anti-war movement of Vietnam can be seen in the opposition to recent wars including the conflict in Iraq that began in 2003. On February 15, 2003, protests were staged in over 600 cities worldwide to express opposition to the impending war in Iraq, which would later be declared in March of 2003 (see slide 15). Despite the subsequent declaration of war, the February protest is considered to be the largest protest event in history thus far. In the tradition of the Vietnam era, teach-ins were also hosted by universities nationwide from 2006-2008 to educate and discuss the impacts and legality of the war in Iraq. Also following in the path of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War is the group Iraq Veterans Against the War (see slide 16), who organized chapters across the nation to voice disapproval of the 2003 war in Iraq, and who continue to be active in warning against continued operations against ISIS/Da’esh in Iraq and Syria.

On slide 17, compare the graph of the left (compiling data from Gallup, Harris, and NROC polls from 1966-1973), which assesses the shift in Americans’ attitudes toward the Vietnam war and toward the military, with the graph on the right (2003-2007 Pew Research polls), which assesses Americans’ attitudes toward the Iraq war and toward the military. What trends do these graphs show? Why might there have been a shift over time?

Regardless of public opinion regarding any current conflict, one of the lessons of Vietnam that has persisted is the need to separate war and warrior—those who serve should be recognized for their service.

Peace activist Tom Hayden discusses how teach-ins to promote peace developed during the Vietnam War.

Thank you to the following reviewers of the curriculum: Andrew Demko, Rainier Junior/Senior High School; George Herring, University of Kentucky; Mark Lawrence, University of Texas at Austin; Susan Tomlinson, Franklin Central High School.

Teachers/Presenters:

Download Presentation – requires internet connection

Download Presentation – does not require internet connection

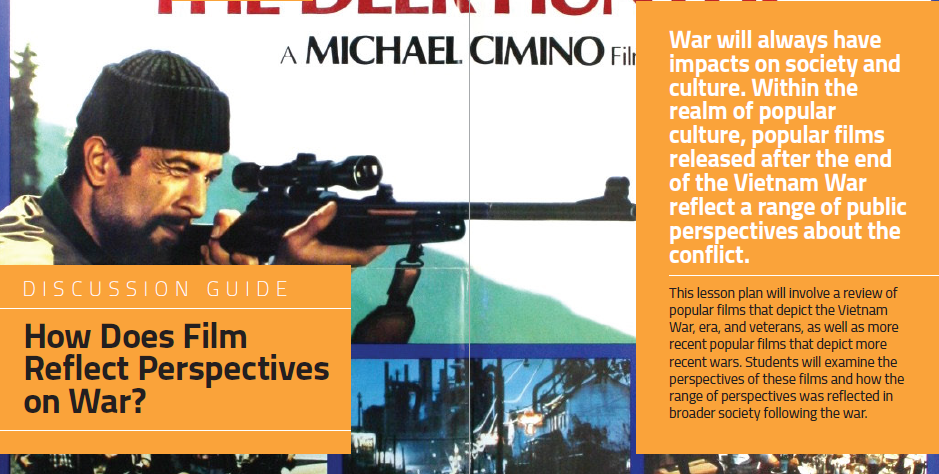

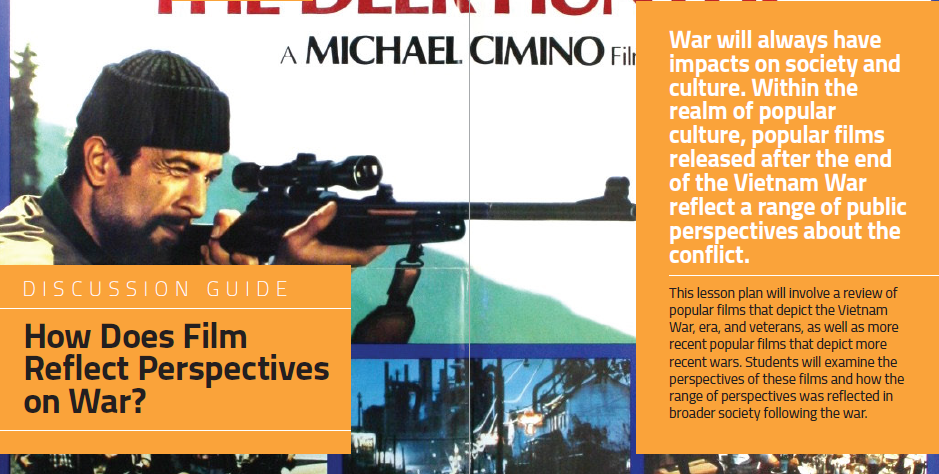

ABOUT FILM AND WAR

Do you think that movies can play an important role in shaping popular understanding of a historical event or period? If yes, how should we interpret them?

One the earliest and most iconic movies to focus on the effects of Vietnam was The Deer Hunter, which was released in 1978, just five years after the signing of the Paris Peace Accords, which ended America’s combat role in Vietnam. The Deer Hunter traces the effects of the war on three young men who served, as well as those at home. The three protagonists all return from Vietnam changed in some way, some more than others. The ending is ambiguous, with one of three dead while the others seem to resume normal lives. Watch the trailer for The Deer Hunter included on slide 1. From watching the trailer, do you think the movie takes a stance on the war? Why or why not? What issues or problems of war does the movie appear to tackle from the trailer?

One year later in 1979, Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now was released, sharing a view of chaos and breakdown of order that came with a war that many questioned. In making the film, Coppola used Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness as a literary basis and parallel to tell the story of a man’s descent into madness in Vietnam. Coppola has been quoted as saying “My film is not a movie about Vietnam. It is Vietnam. It is what it was really like. It was crazy. And the way we made it was very much like the Americans were in Vietnam. We were in the jungle, there were too many of us. We had access to too much money and too much equipment, and little by little, we went insane.” Watch the clip of Apocalypse Now included on slide 2, in which Lt. Col. Kilgore utters often quoted line “I love the smell of napalm in the morning.” What do you conclude about the war from this scene? Why do you think this particular scene and line is often referenced? Does this depiction of Vietnam conform or stray from your understanding of the war?

While The Deer Hunter and Apocalypse Now offer a largely critical view of the war and its lasting effects, a few movies produced in the wake of Vietnam offered an alternative view. One of these was Rambo, the first in the series released in 1982. In the first of the Rambo series, First Blood, John Rambo is seen as a Vietnam veteran who cannot quite find his place in a post-Vietnam America. In one of the most referenced scenes from the movie, Rambo proclaims “I did what I had to do to win! But somebody wouldn’t let us win! And I come back to the world and I see all those maggots at the airport, protesting me, spitting. Calling me baby killer and all kinds of vile crap! Who are they to protest me? Who are they? Unless they’ve been me and been there and know what the hell they’re yelling about!” Watch the trailer for First Blood included on slide 3. How does the trailer’s depiction of John Rambo, a Vietnam veteran, compare to the depictions of veteran characters in The Deer Hunter or Apocalypse Now? Which view of Vietnam and its lasting effects do you find more convincing? Why? Do you think from the trailer the movie takes a stance on the war? Why or why not?

Similarly, 1984’s Missing in Action tells the story of a Vietnam veteran who takes matters into his own hands, seemingly against the wills of all else, politicians and public alike. In the movie, Vietnam veteran James Braddock works to liberate remaining prisoners of war (POWs) in Vietnam, the existence of which has been denied by Vietnamese officials. Despite the release of the last American POWs in 1973, movies such as Missing in Action and the Rambo series perpetuated the belief that some remained despite government claims. Watch the clip from Missing in Action included on slide 4. How would you characterize Braddock? How does the depiction of this veteran compare to the protagonists of the previous films? How does this clip carry forward the popular belief that the war was mishandled by those outside the military?

In 1986, Oliver Stone, a Vietnam veteran, released the landmark film Platoon, which tells the story of a young man’s loss of innocence as he gets entrenched in the war. The film paints a grim picture of Americans in Vietnam, in which troops—many of whom represent America’s working class– turn against each other and turn to drugs as a sense of futility in their efforts increases. Watch the clip of the movie included on slide 5. What popular discourse about the war do you find reflected in this scene? Do you think from watching this scene that the movie takes a stance on the war? How would you characterize protagonist Chris Taylor?

1987’s Good Morning Vietnam explored some similar themes in a lighter context, telling the story of a radio DJ in Vietnam who becomes popular with the “grunts” in Vietnam and becomes involved with a local Vietnamese girl. Though the movie is a comedy, it is a popular film set in Vietnam that has also come to inform public understanding of what the war was like. Watch the trailer for the movie included on slide 6. How does this depiction of Vietnam compare with the depiction in Platoon? What do you conclude about the war from this trailer? Do you think from this trailer the movie takes a stance on the war?

Oliver Stone went on to create another film about Vietnam titled Born on the Fourth of July, released in 1989. Born on the Fourth of July tells the story of Ron Kovic, a real Vietnam veteran who become a prominent activist against the war. After enlisting to serve in Vietnam, Kovic is wounded and paralyzed. He returns to the US, struggles to readjust to his new life, and eventually joins Vietnam Veterans Against the War to protest US involvement in Vietnam. Watch the clip of the movie included on slide 7. How would you characterize protagonist Ron Kovic? Would you characterize him as a hero, an anti-hero, or a victim? What popular discourse about the war do you find reflected in this scene?

Undoubtedly, many students today have seen the 1994 drama-comedy Forrest Gump. While Forrest Gump is not primarily focused on the Vietnam War, the movie depicts the title character Forrest Gump’s time in Vietnam, the antiwar protests that spanned the nation, as well as the process of returning to civilian life following the war. Watch the clip of the movie included on slide 8, in which Forrest Gump is pulled into an antiwar rally on the National Mall to speak on behalf of Vietnam veterans. What impression of the war and era does this scene give viewers? How does this Vietnam-era America compare with the one depicted in Born on the Fourth of July?

The legacy and history of Vietnam continues to be examined in popular film, sometimes expanding upon new subjects or time periods. For example, in 2002 a film adaptation was made of Graham Greene’s 1955 novel The Quiet American, which tells the story of a British journalist and an American CIA agent who live and work together in Vietnam during the period of the war against the French in the early 1950’s. The film was popular in theaters and presented to viewers a nuanced perspective of American involvement in Vietnam, without any clear-cut answers. View the clip of the movie included on slide 9, in which American Pyle and British Fowler meet and discuss communism, liberty, and the French pursuit in Vietnam. How does this snapshot of Vietnam in The Quiet American compare to depictions like those in Apocalypse Now, for example?

In the past 15 years, a number of films have continued the legacy set by the films produced in the wake of Vietnam by interpreting more recent conflicts and the veteran experience. Included on slides 10-12 are clips from three movies: Three Kings (1999), The Hurt Locker (2008), and American Sniper (2014). Three Kings is set during the 1990 Gulf War, and tells the story of American soldiers who set out to return gold plundered from Kuwait during the war; The Hurt Locker is set in the 2003-2011 Iraq War, and tells the story of a divisive sergeant who works with a bomb disposal team; American Sniper is also set in the recent Iraq War, and tells a fictionalized account of real-life Navy SEAL Chris Kyle and his struggle to readjust at home after serving as a sniper during the war. Compare:

How soldiers or veterans are depicted in each, and how those depictions compare with depictions in Vietnam films;

Whether the movies seem to take a stance on the respective wars;

Whether and how popular debates about the respective wars can be seen within the clips

Since the Vietnam era, film has been used to reflect a range of perspectives on war, a tradition which continues into the 21st century. Some films continue to interpret the Vietnam experience, such as 2002’s We Were Soldiers, which tells the story of the Battle of Ia Drang, considered to be the first major battle between US forces and North Vietnamese forces. Now a part of the story of our nation’s history of the war, the Vietnam Memorial is featured in the film as a place where the protagonist goes to find peace (slide 13).

Thank you to the following reviewers of the curriculum: Andrew Demko, Rainier Junior/Senior High School; George Herring, University of Kentucky; Mark Lawrence, University of Texas at Austin; Susan Tomlinson, Franklin Central High School.

Teachers/Presenters:

Download Presentation – does not require internet connection

ABOUT MUSIC AND WAR

What songs can you think of that deal with the subject matter of war and peace? Are there other songs that are more broadly either highly patriotic, or highly critical of problems in the nation? Which are your favorites, and why?

In the early days of the war, songs like Sgt. Barry Sadler’s “Ballad of the Green Berets” received extensive radio play—“Ballad of the Green Berets” reached #1 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1966. Listen to the song as it plays through slides 1-3. Sgt. Barry Sadler served in Vietnam and wrote the song to celebrate the Green Beret Special Forces. This song has a clear perspective that celebrates the contributions of soldiers, yet it does not explicitly discuss political concerns or more broadly interpret the war.

Three years before the Ballad of the Green Berets topped the charts in 1966, Peter, Paul and Mary’s cover of “Blowin’ in the Wind” topped the Billboard charts, reaching #2 in 1963. The song, originally written by Bob Dylan in 1962, has come to be identified as perhaps the quintessential anthem for peace because of its widespread adaptation by the public to express disapproval of the Vietnam War. Listen to the song as it plays in slides 4-5, answering the song analysis questions. This song was not explicitly written to voice a perspective on the Vietnam War. How does it compare with “Ballad of the Green Berets?”

A few years later, as the war progressed, the public grew increasingly disillusioned with the war, with disapproval ratings reaching 64% in 1970. That same year, Edwin Starr’s performance of the Temptations’ song “War (What Is It Good For)” topped the Billboard charts at #1. Listen to the song as it plays in slides 6-7. How does a song like “War” compare with a song like “Arms for the Love of America” (from the pre-visit activity)?

In the years following the Vietnam War, there were also songs that interpreted the post-war experience—specifically the negative aspects of the post-war experience—that became popular. In 1982, the same year that the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was dedicated, The Charlie Daniels Band released a song titled “Still in Saigon,” written from the perspective of a Vietnam veteran unsure of his place in the world after his return from war. Listen closely to the lyrics as the song plays in slides 8-9. What issues are mentioned that returning veterans may have to face?

The Vietnam era set a precedent for music as a public space to reflect perspectives on war, with critical perspectives being acceptable and potentially even popular. With the outbreak of war in the Persian Gulf in 1990, Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the USA,” though originally released in 1984, gained prominence as a patriotic song of support for troops serving in the Gulf War. Though the song was not written in the context of war, it was readapted by the public in order to voice support in a time of war. Listen to the song as it plays in slides 10-11. Do you think it is possible to identify an overall expression of approval or disapproval for war in this song?

Even more popular than “God Bless the USA” was Bette Midler’s “From a Distance,” reaching #2 on Billboard’s Hot 100 in 1991. Listen to the song as it plays in slides 12-13. The song, originally written by Julie Gold in 1985, is again not explicitly centering on war as a subject, though it was adopted by the public as both an expression for peace and longing for the return of troops.

On September 11, 2001, a global terrorist group known as Al-Qaida coordinated a series of attacks on the US which left over 3000 civilians dead at the World Trade Center in New York, the Pentagon in the Washington, DC area, and at a plane crash site in Shanksville, Pennsylvania. Play a small portion of the live video coverage from 9/11 included on slide 14. Following the attacks, “Only Time,” a song by Irish singer Enya that had been released the previous year in 2000, quickly rose to #10 on the Billboard Hot 100 charts as Americans adopted the song’s mournful tone and message for the current tragedy. Listen to the song as it plays in slides 15-16.

Two years later in March 2003, the US invaded Iraq in search of nuclear weapons, in what marked the beginning of the eight year war in Iraq. Listen closely to Toby Keith’s 2003 song “American Soldier” as it plays through slides 17-18. How does this song compare with Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the USA?” Do you think it is possible to identify an overall expression of approval or disapproval for war in this song?

As the war in Iraq progressed, Americans’ approval for the war steadily decreased, with CNN polls showing over 60% public disapproval of the war by 2006. That same year, Pearl Jam released “World Wide Suicide,” a song written by the group’s lead singer Eddie Vedder about Pat Tillman, a professional football player who turned down a contract with the Arizona Cardinals to enlist in the US Army. Tillman served in Iraq and Afghanistan, and his story became popular with the public after his death in 2004. The song, which reached #41 on the Billboard Hot 100 charts in 2006 and #1 on the Billboard Modern Rock charts, is critical of the war, while recognizing the service of soldiers like Tillman. Listen to the song as it plays in slides 19-20. How does this song’s perspective on war differ (or not differ) from a song like Edwin Starr’s “War?” Why do you think there is a more explicit separation of war and warrior in the songs of more recent times?

Since the Vietnam era, music has been used to reflect a range of perspectives on war, a tradition which continues into the 21st century. That civic dialogue that can be traced through popular music has included reflections on the post-war experience of remembering the fallen at The Wall. In 2014, Bruce Springsteen released a song titled “The Wall” which tells the story of visiting the Vietnam Memorial to reconnect with a friend. The song was written after Springsteen visited the Vietnam Memorial and decided to write a song in honor of his friends and fellow musicians Walter Cichon and Bart Haynes who died in the war.