I think Dad would love to be remembered as someone who made people laugh. Particularly as somebody who embraced a country that was not the country of his birth and who loved it enormously and wanted to give back to those people that were willing to put their lives on the line for their country. – Linda Hope

Born in England, raised in Ohio, Bob Hope originally got in to show business doing vaudevillian and comedic work. His midwestern work ethic pushed him into stand-up comedy, Broadway, films, and song. Hope’s unique style of dance brought joy to millions and the ability to do it all arguably made Bob Hope a man worth remembering. However, what set him apart and established his legacy was his commitment to the military men and women who served overseas. Hope’s unwavering support for the troops earned him the unique privilege of being named an “Honorary Veteran” by the Secretary of Veterans Affairs.

The Beginning . . .

When Hope heard about the bombing of Pearl Harbor, he wanted to do a show for service members and give back to the men and women serving in our nation’s armed forces. In doing so, he made a decision that would forever alter the course of his career. Hope took his show on the road, broadcasting from military bases around the country. His commitment to the war effort continued when he joined the Hollywood Victory Caravan, helping to raise money for Army and Navy Relief Funds. In 1941, when Armed Forces Radio started its own programming, Hope signed on. In 1942, while visiting service members in Alaska, he told reporters, “Yes, Hollywood won’t see so much of Hope from here on out. I’ve got other plans.”

Hope’s trips from 1941 to 1991 took him on 57 tours with the USO while he entertained the troops in every major military conflict including WWII, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and Operation Desert Storm (Persian Gulf War). One service member recalled, “Hope was funny, treating hordes of soldiers to roars of laughter. He was friendly – [he] ate with servicemen, drank with them, read their doggerel, listened to their songs. Hence boys whom Hope might entertain for an hour anticipated his arrival for weeks. And when he came, anonymous guys who had no other recognition felt personally remembered.”

His strength was in his relatability to find the humor in the darkest of days, and the clarity of his compassion for troops serving overseas. Those strengths would come to best serve him during the Vietnam War, when our country was unsure where to tune in, what to tune out, and some days, where to even locate a laugh.

1964

As early as 1962, Hope requested to tour Vietnam and was given the green light by President Johnson after the Gulf of Tonkin Incident in 1964. Hope and his crew headed to Vietnam in mid-December, stayed to entertain the troops through Christmas, and then headed back home. His monologues were packed with jokes about being mistaken for a soldier, “What a welcome I got at the airport…They thought I was a replacement.” And frequently referenced the enemy, “And incidentally if there are any Viet Cong in the audience, remember I already got my shots.” These lines garnered cheers from the boys below facing these very real consequences.

Footage of Hope’s performances throughout his tour were produced into TV specials aired later back in the United States. As Hope told jokes on stage, cameras panned to young men in uniform, some injured and all laughing, enjoying a lighter moment with friends before being returning to the realities of Vietnam. A lucky mother might glance an image of her son, an even luckier service member might be called on stage for the opportunity to introduce Bob Hope or be read a greeting from home. That year the Christmas special ended in Vietnam the way all future specials would with the crowd softly singing, “Silent Night.” A somber end to an evening packed with joyous laughter.

When airing the special at home in the United States, Hope attached his tribute and thanks to the boys overseas. These pieces would continue on and offer insight into not just Hope’s feelings about the troops, but also his feelings about America’s involvement in the war. His rhetoric in 1964 was reminiscent of many at home, who thought the war would end in a quick victory, “they’re (American service members) not about to give up – because they know if they walked out of this bamboo obstacle course it would be like saying to the Commies- ’Come and get it‘. “

1965

Hope headed back to Vietnam, and with increasing troop levels he continued to see increases in attendance at his shows. He used this as material joking, “Last year you were all advisors. Now that you see where it’s gotten us, maybe you’ll keep your trap shut.” He also continued jokes about military rations. “The Pentagon really went all out on this flight. They even showed a movie. It was very exciting – 300 ways to cook ’C’ rations,” and his own lack of service, “I see where they did away with my old World War II classification – 4z…That’s ’conscientious coward.‘ In case of an invasion I stay behind the lines and pile Jackie Gleason around Bing Crosby.” Hope started to hint at a growing discontent in the United States joking, “We’ve had all kinds of demonstration back in the states… Get out of Vietnam, Don’t get out of Vietnam, Why don’t you go back to where you came from and “I came from Vietnam.”

In An Khe, Bob pulled Specialist Brian H. O’Connell on stage, “Here’s a picture of twins. His twins that he’s never seen. Right here. And I just want you to take a peek at these little kids. That’s the first time he’s ever seen them. Those—” but Hope couldn’t finish his monologue as the shouts and cheers from the audience drowned him out. Throughout the show, there were moments like these, where his love for the service members was evident. Continually, he offered them a glance of the life waiting for them back home and reminded them what they were fighting for.

When the special aired back home, and the jokes had been told, and Silent Night had been sung, Hope offered his tribute, “Our fighting men have confidence in the decisions of their leaders. It’s hard for them to hear the rumblings of peace over gunfire, but when peace comes, they’ll welcome it.” Turning away from jokes, Hope offered a gentle reminder that these “boys” were delivering on the confidence of their “leaders,” but that they needed the American public to stand with them as well.

1966

In 1966, men crowded rooftops, climbed to the tops of light poles, and shimmied under the stage – all to get a glance of Bob Hope. His specials in Vietnam were to bring humor and joy overseas. He called men on stage, often making a joke about their home states, sports teams, or reading them notes from home that ended with a kiss from a travelling girl, or even from Hope himself. Another of his favorite subjects for ridicule — ranking officers.

“This base is loaded with brass. You can’t walk five feet without saluting. They have more guys in the hospital with tennis elbow than they do with shrapnel.”

Hope knew that jokes about the men in charge would always bring big laughs, offering lower rank service members the chance to commiserate with one another. As Hope headed to more stops in Vietnam than ever before, he never hesitated to talk about the protests and frustrations of what was playing out back home. “The country is behind you, 50 percent,” he quipped at Cu Chi. Followed by, “Actually the defense department was very sporting. This year they gave me my choice of either combat zone…Vietnam or Berkeley.”

Looking at his commentary, and the many protests forming around the country at the time, Hope’s frustration with the lack of support was not unusual, but rather on par with so many others. Hope’s tribute in 1966 came with a message of reflection for the American people, “Nobody wanted this war, but it’s here, and we can’t wish it away. There’s no easy solution…the boys fighting in Vietnam want peace as much as we do, and they’re fighting to get it.” Through these words we can hear the plea to the American people about the importance of separating the war and the warrior. Bob Hope realized that the growing discontent at home was becoming muddied and turning in to a growing discontent for those fighting the war, and for him that was never an option. Hope’s commitment to those who served was absolute.

1967

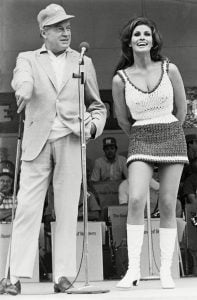

Credit: AP/Shutterstock

Bob Hope and Raquel Welch share the stage as they entertain the troops in Vietnam in 1967.

In 1967, with troop numbers rising, Hope quipped, “Look at these cats…they’re lying with their bodies under the stage and their faces staring up at me.” The camera panned to the service members with their heads poking out and then the thousands in the crowd, evident that Hope’s popularity was ever increasing in Vietnam. Jokes about service branches – “And we have the 101st Airborne here today. The only outfit in Vietnam that travels by Yo Yo.” On individual jobs, “You can always tell helicopter pilots…They’re the ones that are still doing the Watusi a half hour after they land.”- generating laughs so hard that Hope often had to wait for several seconds before he was able to move on. It was Hope’s familiarity with the wartime situation and his ability to look at it as an outsider that granted him the ability to connect with service members.

Hope carried on with humor about the danger zones of the war, “And the guys love it here because Da Nang has such a wonderful location. It’s so handy to downtown Hanoi.” And the area to which he was performing, in referencing Thailand, “this country’s never been conquered. And no wonder…Nobody can get through that traffic.” In regional humor like this, service members laughed, but also clapped and cheered as if someone was finally talking about the local realities that only they can understand. It was funny for us at home, but for them it was also catharsis; the opportunity to laugh at a sometimes unbearable situation that you just had to survive. Hope made that situation relatable, and therefore bearable.

The year also brought discussion of protests at home, “Men, I bring you great news from the land of liberty….It’s still there…You may have to cross a picket line to see it, but it’s there.” It’s here that Hope first mentioned that service members might face challenges with civilians upon returning home and perhaps foresaw some of the issues they would face back in the United States. Bob ended the 1967 special with a visit to a hospital, “The big topic of conversation is how many days you got left? Most of these kids have it tattooed on their eyeballs.” And “despite the millions of words that have been spoken and written, we know there are no easy answers to this conflict. But an answer there must be…We hope and pray that before too long the peace for which we are all yearning will become a reality.”

1968

In 1968, Americans lived through one of the most tumultuous periods in American history. As tensions unraveled at home, Hope brought it out in his overseas shows, ”I’d like to spend Christmas in the states, but I can’t stand the violence” and “last year they were burning their draft cards…this year – it’s the schools.” Offering humorous advice to service members Hope stated, “So when you muster out, keep your rifle…If you go to school under the GI Bill you may have to recapture it first.” Hope also joked about the end of Johnson’s presidency, “And of course I wish LBJ all the luck in the world, he’s had a rough time, you know. In fact, the other day he went over to the Lincoln Memorial and he looked up at Abe and he said, ‘you had a war…you had a civil rights problem…what can I do?’ and there was a pause and finally a voice said, ‘Don’t go to the theatre.’” Hope’s shows were more tinged with the realities from home than ever, and it offered service members an opportunity to see the support that the USO and Hope continued to offer.

At the end of the 1968 special Hope stated, “Discussions about our posture in Vietnam go on and on. The rights and wrongs of it are being debated and will continue to be debated for years. But one thing is not debatable…and that is the contribution our men have made in Vietnam. Their courage, their kindness, their humanity and their sacrifice can never be undone. It’s now a part of history.” It is here that Hope worked to grab from both sides of the aisle, “whether you support the conflict or not, the young men we’ve put forward to fight in it should receive our committed support.” He finished with “But here we were again, and somewhere along the way the realization hit me that we were trapped in a kind of quicksand…that there was no end in sight, and that we were paying too high a price in our greatest natural resource…our youth.” Time and again we saw Hope’s ability to separate the war and the warrior and his unwavering commitment and support to the people on the ground fighting the battles. Hope recognized the “quicksand” that our country was becoming caught in, but he refused to be sucked in, choosing rather to cheer for the service men and women he had always supported.

1969

Hope headed out in 1969, twenty-one years after his first USO trip to Germany with 80 other performers and nine countries to play to. Before they left, Hope and his troupe played a dress rehearsal at the White House, joking, “I’ve never done a complete show at the White House, although I’m not complaining. It took some acts twelve years to make it,” proving that not even the commander-in-chief, Richard Nixon, was safe from his barbs.

His topics on bases included the new draft lottery which had only recently gone into effect. “And for the information of you fellows up for rotation—they just had a new draft lottery and if you hurry home you may win it! I know you’re all thrilled about the new draft lottery. The big thrill for you is realizing you’re last year’s winner!” Hope also went after the problematic issue of a discussed neutral Laos where the Ho Chi Minh Trail ran into and which was being used by enemy soldiers to transport supplies. In Nakhon Phanom, Hope stated, “At this moment we are only about 4 miles from the Mekong River and only nine miles from neutral Laos. Yes sir. Yes sir. And if you listen carefully, you can hear the neutral troops carrying the neutral ammunition down the neutral Ho Chi Minh Trail.” In these jokes the cynical feelings that some service members may have had were given voice and laughter to help work through a grey area.

Hope’s tribute in 1969 stated, “A lot of people ask me if I’ve noticed any change in our situation this year from what it was last year. One thing never changes…the unbelievable good spirit of our fighting men. The only thing that qualifies as business as usual is the incurable humanitarianism of our average G.I. The number of them who devote their free time, energy, and money to aiding Vietnamese families and caring for orphans would surprise you. Or maybe it wouldn’t – I guess you know what kind of guys your brothers, and the kids next door are.” It is here that Hope called on the American people to remember the kindhearted kids they sent overseas. He was not ‘hawking’ the war, but rather asking Americans to think about service members as the goodhearted people they sent off to Vietnam.

He continued, “These kids are concerned about morale back home. If you wonder who’s in charge of war-front morals, you are. And what these guys read in the newspapers and hear on TV that tells em’ you’re behind em’ is like a big heart transplant from you to them.” “These are men who lay their lives on the line every day. And in return they ask for one thing…time to do a job. For us to be patient, to believe in them, so they can bring us an honorable peace.” Hope ended 1969 with a task for Americans, “believe in them.” The line, which seemed so small at the time, would come to show the divide for so many service members who returned back home to hostile situations.

1970, 1971 and 1972

The 1970 USO tour started with a dress rehearsal at West Point, Hope declaring, “No, I haven’t seen so much gray since I passed out at the letter carrier’s convention.” In Da Nang, Hope stated, “This is our seventh trip here. Isn’t it amazing the pull I have with the Department of Defense. No, this is the only base in Vietnam with rapid transit. There’s a rocket going any place you want…and a few places you don’t.” In Long Binh, Hope hinted towards the withdrawal of troops, “This is the biggest military installation in Vietnam with twenty-five thousand men. And with all the troop withdrawals, I’m surprised to see anybody here. It was nice of you guys to stick around just for me.” That joke, “it was nice of you guys to stick around just for me” appeared until Bob Hope’s trips to Vietnam came to an end in 1972. The realization that service members were going home was a happy acknowledgement for him, and one he used in his show again and again.

Hope did not hold off with his typical material, keeping political in 1971 with, “You guys are lucky. You know you’re going to get home. But what hope is there for our men at the Paris Peace Talks?” and in 1972 “Not only did they fail to reach an agreement in Paris…but now they’re fighting over the hotel bill.” Still there were jokes about ranking officers, “There’s so much big brass here, the GIs sleep at attention.” And his classic use of self as a punch line, “Here I am to share Christmas with you. And I bet some of you guys were afraid you wouldn’t have a turkey, huh?” The classics still brought in the laughs, even from a withered down audience.

In 1970 Hope stated, “Everyone agrees that this most unpopular of wars has lasted too long. But now, for the first time, we can see the light at the end of the tunnel. They are coming home, although never fast enough when someone you love is involved.” In 1972, “But this time in Vietnam, we ran into a situation that would ordinarily take the heart out of any performer, but which to us was reason for rejoicing. I mean – clusters of empty seats during our shows at Da Nang and Camp Eagle…because every empty seat meant a guy who’d returned home, a GI who’d gone back to “the world.” Hope was no longer asking the American people to support the overseas action, but rather to welcome and honor the boys who came home. His commitment to them was evident in his last send off in 1972 where he stated, “We’ll never forget them…The ‘river rats” at Dong Tam, the “dust offs” at Cu Chi, the ‘jolly greens’ and the ‘sandys’ at Nakaon Phanom, the grunts at Pleiku, the marines at Da Nang and Chu Lai, and all the fighter pilots on the carriers on yankee station on the South China Sea: And just a couple of headlines ago the B-52 crewmen who braved flak filled skies over North Vietnam they all met the challenge with fantastic courage and good humor.” Hope mentioned specific crews and allowed the boys watching back home to know that their lives in these small, often unknown locations were known to him because of their bravery and their service. Forcing the American people to reflect on the service branches fighting in Vietnam as more than just a monolithic experience. The nicknames and locations reminded us of the vast war we involved ourselves and the risks we sent our sons off in to fighting it.

Conclusion

At a time when so many Americans were divided over the Vietnam War, they weren’t divided over Hope. In 1970, Hope drew 46.6 percent of American homes to his January special, the largest television special ever broadcast. While Americans watched service members fighting on the evening news every night, Bob Hope offered a different perspective. He brought sons, brothers, and husbands back home to their living rooms. He showed us our men overseas smiling and laughing, as if perhaps, in that moment, everything was alright. Going back and watching the clips, his sincerity and caring for service members was palpable, and when he hit the punch line, the response was always an uproar of laughter and applause. His tributes were reflective, taking time to honor and thank the young people he had just performed for, but also show the tenor of our nation’s attitude about Vietnam and how it evolved. His beginning tributes with an overall belief that this would be a quick and just war is what so many Americans also thought. And as seeds of discontent were slowly sewn so do the tributes slowly changing to pleas, bartering, and eventually empathy of the frustrations of watching so many young men slip through that “quicksand”. However, Hope never wavered on his commitment to the troops. He never stopped performing, showing up at hospitals, and bringing messages of love and support. His last USO tour was in 1991, but perhaps a more fitting memory was his Kennedy Center honors in 1985. Hope was thanked by famous comedians, President Ronald Regan, and many others, but only one group brought him to tears – veterans. World War II, Korea, and Vietnam, so many stood up to remind Hope of the joy he brought into their lives and the emotions rolled down his cheeks. Bob Hope’s last Christmas special ended with a fitting tribute for the Kennedy Center moment he where softly stated, “Thank you for Christmases I’ll never forget. Good night.” Hope was honoring and thanking service members, but the same could certainly have been said to him.