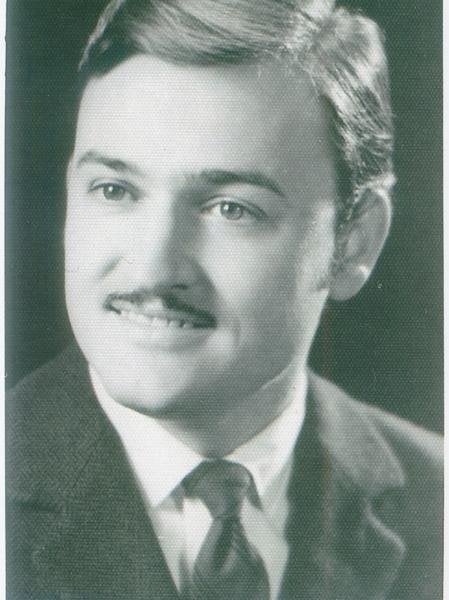

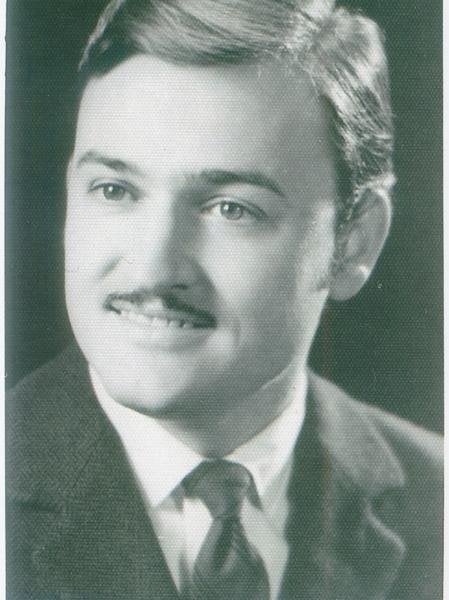

JOSE L. MONTES

“A Simple Day” by Yolanda Acevedo

Dad and I left the house early. As always, we had breakfast together. It was still dark outside, but I did not care. That day was going to be just Dad and me.

As we went through the base gates, there was a soldier there. At that moment, I realized that they were always there, a familiar and constant feature in my childhood universe. We went to Dad’s office and said hello to different people. Most I recognized; some I did not. Many had been to our house on different occasions—for parties, to say hello or just to talk. It was 1968, and we were in the middle of the Vietnam War. I guess that during difficult times and being far away from home, friends became family. I remember back then, we had a lot of family!

It was a beautiful spring day in paradise. After lunch, Dad and I played golf. I had never played golf before that day. I think that, like many things in life, golf is something that you either like or you don’t. I do not like golf. I never have.

That day, however, it was different. That day, I loved golf. It was our special day, and for a little girl who adored her father, it was heaven. Dad tried to teach me to play the game he loved, and I loved every minute of it. We talked, walked and laughed all through the golf course while trying unsuccessfully to play. We shared stories and dreams all day long.

It was the perfect day, just my best friend and me. As time passes by, some memories start to fade, while others remain. I have many memories of Dad, but the images and feelings of that day will stay with me forever.

Years later, I learned that Dad had received deployment orders just a week before our little outing. He was going to Vietnam. He was going to leave me behind. Soon after, he was gone! I was alone and, for the first time, I experienced loneliness. There would be no more breakfasts together, no more playing golf or singing, and no more walks for Dad and me. He left, never to come back.

Among the personal items returned to us by the Army were pieces of Dad’s rosary. He always wore it around his neck. Years later, I decided to put together the remaining pieces. On my wedding day, I hid it in my bouquet. No one knew.

We were deprived of so many days, but not that day. In a very simple and quiet way, he walked down the aisle with me.

We had one more walk together, Dad and me.

JOSE L. MONTES is honored on Panel 41W, Row 25 of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

JEAN MASON KRAUS

“My Cousin Jean” by Lt. Col. Janis Nark, USAR (Ret.)

Jean Mason Kraus was the youngest of three exceptional boys who were my favorite cousins. They were teenagers back then: fun, handsome, intelligent, full of life. I was six years younger and rarely, if ever, noticed by them.

Every summer when I was young, we would pile into the Ford and drive from Detroit to Grandma and Grandpa Mason’s farm in Novelty, Missouri. That constituted our official summer vacation trip.

When we first started that tradition, water at the farm was drawn from the well, and the toilet was through the chicken yard along a wooden-planked path to the outhouse. We thought this was great adventure. There were cows, pigs, horses and chickens. The food on our dining table came from all but the horses, and the rest came from the fields and my grandmother’s garden out back. She used the Farmer’s Almanacand planted by the moon. She grew the sweetest sweet corn and the biggest, ripest, reddest, most delicious tomatoes in the world.

My favorite relatives lived near Lake of the Ozarks, and it was always a time of great excitement and fun when we could go visit them. Aunt Marie was the mother of the three outstanding young men: my cousins Jean, Bill and Sam. She was short, pudgy, outgoing, warm and funny. She personified love like no one I’d ever known in my short life. They had a homemade pond with a raft in the middle where we’d all go swimming in those peaceful days of the 1950s.

It was a special treat to go to Lake of the Ozarks. We would go boating with our relatives on the lake, as the old 8mm movies from that time show us doing over and over again. In one of those movies, I’m sitting in the back of the boat next to cousin Jean as it’s leaving the dock. I’m trailing my fingers in the water, imagining that I look very much like Marilyn Monroe. What I look like is a very geeky kid with a frizzy home perm. He is oblivious to me, and I am madly in love with him.

Jean went on to college and became a teacher and an incredibly talented artist. He painted beautiful, tranquil and deeply emotional pieces in oils and watercolors. The ones I saw were always scenes of nature, of rivers, of the land he so loved.

When he was drafted, it never occurred to him not to go. He didn’t choose to be an officer, though that was offered. No, he would just go, do his duty and then come home to his life of teaching and painting. He wasn’t meant to be a soldier; he was a soft, kind and gentle spirit. The Army made him a grunt.

I had joined the Army in nursing school and was at my first duty station, Madigan General Hospital at Ft Lewis, Washington, in 1970. We were busy of course, with busloads of wounded Vietnam vets coming into our wards daily. I was young and naïve, but getting older every day.

My parents came to visit from Michigan, and I enjoyed remembering and feeling what life was like before the Army and the war. Then they told me that cousin Jean had died in Vietnam the week before. All the report said was that he died instantly when he stepped on a booby trap.

My heart broke into a million pieces. One more beautiful soul was gone.

I know his paintings live on. I know that those children whose lives he touched, even briefly, are better for knowing him.

I miss him still.

JEAN MASON KRAUSis honored on Panel 8W, Row 86 of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

JONATHAN CAMERON SHINE

“He Was Brilliant—and Nice” by Col. Alexander P. Shine, USA (Ret.) and Gail Caprio

On Oct. 15, 1970, Army 1st Lt. Jonathan C. Shine was leading his platoon of the 25th Infantry Division in the Iron Triangle area of Vietnam when they became engaged in a fierce firefight with a much larger enemy force. Ignoring a head wound, Jon encouraged the platoon medic to take care of another soldier. A few minutes later, Lt. Shine was dead.

Those who knew Jon during his school days would remember him as a multi-talented young man. Consistently a top student, he was a “Star Man”—in the top 5 percent of his class—all four years at West Point. Jon was also an athlete and leader. But the qualities which most stood out in Jon were his integrity and his warm friendliness and interest in everyone he met. People respected Jon because he lived in accordance with a high code of integrity and honor; and they liked him because he genuinely liked them, whatever their status or position in life. As a West Point classmate said of him, “Jon Shine was a class act.”

As president of his Briarcliff, N.Y., high school student body, Jon and his equally talented vice president, Gail Morrison, stood at the top of their class, while also developing a friendship which grew deeper and led to their marriage in February 1970. Only a few months later, Jon shipped out for Vietnam. Gail was attending the funeral of one of their friends, another soldier, when the news of Jon’s death reached her. With the courage of a soldier’s wife and faith in God, Gail rallied and was an encouragement to many others as the body of this outstanding young man, and the love of her life, was laid to rest in the West Point cemetery.

The youngest of four siblings—all of whom served in Vietnam—Jon was the first to be killed, but sadly he would not be the last. A little over two years later, the oldest of the Shine children, Lt. Col. Anthony Shine, an Air Force fighter pilot, went down during a bombing run and was missing in action for nearly 25 years before his remains were recovered and buried with full honors in Arlington National Cemetery.

Any description of Jon Shine would be incomplete without mention of the central focus of his adult life: his strong and steadfast Christian faith. Jon surrendered his life to Jesus Christ as a plebe at West Point and, consistently through his cadet years and the 16 months of Army service that followed, he sought to live a life that would serve men and bring honor to God. In a letter to his brother Al, who was serving in Vietnam during Jon’s senior year at West Point, Jon quoted Psalm 27:1: “The Lord is my light and my salvation – whom shall I fear? The Lord is the strength of my life – of whom shall I be afraid?” He faced life and death with courage born of confidence in the Lord.

As his widow, Gail, said of Jon, “He was brilliant; but he was nicer than he was brilliant.”

JONATHAN CAMERON SHINE is honored on Panel 6W, Row 2 of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

ANTHONY CAMERON SHINE

“Overcoming Incredible Odds” by Anthony, Colleen, Shannon and Bomette “Bonnie” Shine

Before volunteering for his second tour of duty in Vietnam, before escorting his youngest brother’s body home for burial, even before joining the United States Air Force in 1961, Tony Shine was a man of character and perseverance. He was a big man, standing a few inches above six feet and weighing in at 230 pounds. Physical fitness was his lifelong tenet for being the best he could be.

In grade school, Tony was handsome and smart, the consummate Norman Rockwell picture of a healthy, vibrant “boy’s boy.” Fittingly, his first love before flying was football. Tony relished the competition, team discipline and excitement of the game. When he was 11, tragedy struck Tony in the form of polio, a crippling disease that struck fear in the hearts of families across the United States. So many who contracted the disease would be paralyzed by it; some would die from it.

Tony was bedridden with polio for many long months—no more running, blocking or tackling, just lying still, exercising his mind and will to recover. When he finally succeeded in defeating polio, Tony’s body was weak and atrophied. His left hand was so badly ravaged that muscle transplant operations were necessary to restore use of his thumb. His physical deterioration was such that he couldn’t pick up or hold a pencil with either hand. Doctors explained that the damage to his muscles was so severe he would be lucky to walk normally again, let alone to play football.

Devastated but not defeated, Tony made a decision not to quit. Drawing on a determination and self-discipline that would become his hallmark, he was diligent with his physical therapy, pushing himself to do more and to be more than his doctors deemed possible. In a matter of months, the boy who could not pick up a pencil or write his name, even with his good hand, had overcome the odds. Through tenacity and arduous physical therapy, not only did Tony learn how to write again with his right hand, but he could write equally well with his left.

Once he could stand, Tony rebuilt his body and his life. He learned to walk without a limp and began training so he could try out for his high school football team. At first, it was difficult; the cheerleaders on the sidelines could run up and down the field faster than he could. Yet he never gave up. Eventually, he earned a place as a starting player on the varsity team. And later, he went on to become a starting player in college football for Colgate University.

Following the muscle transplant surgery, growth in Tony’s left hand was stunted, and it always remained considerably smaller than his right. This malady could have disqualified him from being an Air Force pilot, let alone a fighter pilot, with its uniquely stringent physical requirements. Again, Tony met the challenge and overcame it. He used weights and, for years, carried hand grips in his coat pockets so he could exercise his left hand.

Early in his Air Force career, Tony served as an instructor pilot. Leading by word and example, he encouraged his students to work harder and to persevere to reach their goals. Drawing on his personal experiences and one of his favorite poems by Rudyard Kipling, “If,” Tony challenged his students. Sometimes, he would say, you must “force your heart and nerve and sinew to serve your turn long after they are gone, and so hold on when there is nothing in you except the will which says to them ‘hold on.’”

Lt. Col. Anthony C. Shine, USAF, was missing in action from 1972-1996, when his remains were repatriated and interred at Arlington National Cemetery. The U.S. Air Force’s top gun award, the Lt. Col. Anthony C. Shine Award, is presented annually to the USAF fighter pilot who most exemplifies Tony’s caliber of character and his professionalism in flying a tactical fighter aircraft.

ANTHONY CAMERON SHINE is honored on Panel 1W, Row 93 of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

KEITH ALLEN CAMPBELL

“Living Life to the Fullest” by Judy C. Campbell

Live, laugh, love. When I think of my brother Keith Allen Campbell, I think of those three words. Keith was the epitome of someone who lived life to its fullest.

Sadly, he left this earth on Feb. 8, 1967, while serving in the U.S. Army in Vietnam with the 173d Airborne Brigade (Sep.). An Army medic, he used his body as a shield to protect a fellow soldier after he had provided life-saving medical treatment. Keith had already served in the Dominican Republic with the 82nd Airborne Division and had received his Honorable Discharge. But he re-enlisted as the Vietnam conflict heated up, because, he said, “My medic skills are needed.”

Long before he was an Army medic, he was my big brother. I vividly remember playing with my Barbie and Ginny dolls, taking a blanket and cardboard to partition off rooms as if I were making my own little dollhouse. Often, I was teased for this—playing with dolls long after many of my girlfriends became interested in boys—but Keith never teased me. Instead, he often made splints for my dolls, as I pretended they fell and broke a leg or arm.

Keith always wanted to become an Army doctor, and I wanted to become a nurse; we shared a common bond in this field. His Boy Scout troop #165 at Mt. Olivet Church in Arlington, Va., always won the first aid competitions because of Keith’s efforts. In addition to giving medical treatment to my dolls, he also helped patch up the local kids as he got older. I was always his ready and willing nurse, no matter who the patients were!

Our mother, Esther B. Campbell Gates, saw Keith’s interest in medicine early on and invested in a set of medical encyclopedias, which Keith read cover to cover several times. Later, when my children were growing up, I would often reference these books.

Over the years, Keith caught me opening my Christmas presents early, then rewrapping them so no one would know I had been peeking. I just could not wait for Christmas morning! Over the years, he liked trying to frustrate my attempts at getting a preview of my gifts—for instance, taking an entire roll of Scotch tape to wrap my gift.

But, I will never forget Christmas 1961; I think Keith was more excited than I was! Our front hallway door was always open, so it was not unusual for it to be open that Christmas morning. But for some reason, Keith kept an eye on it, making sure nobody closed it. We began taking turns opening our gifts, and when it was my turn, Keith said, “Judy, go close the hallway door.”

When I did, there behind the door was a life-sized doll for me! She was the size of a three-year-old child. I still have “Peggy,” as we named her, and now my granddaughters play with her.

Keith was not only my big brother, but he was also a father figure, someone I truly looked up to for advice. I was amazed at how many people loved and respected him. He was adventuresome, but not reckless or careless. School bored Keith, as he was a hands-on type of guy and in many ways was self-educated.

Being a medic in the Army was just the first step in my brother’s life plan, in which he eventually saw himself becoming a doctor. While he never was able to complete all he wanted to do, he did use his medical skills to help many people before he died. While on maneuvers with the 11th Special Forces, his first sergeant walked into a tree limb. Keith immediately knew that time was of the utmost importance and surgically removed the limb, saving his vision. Sgt. Wood remains in contact with our family to this day.

SP4 Keith Allen Campbell gave his all during his life, and his memory will live on for generations to come. In my heart, I will always be honored to say that not only did I know Keith Allen Campbell, but I was blessed to be his baby sister.

KEITH ALLEN CAMPBELL is honored on Panel 15E, Row 8 of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

REX MARCEL SHERMAN

“An Ideal Son” by Ann Sherman Wolcott

My son Rex Sherman was born on April 8, 1951, the week of Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s famous retirement speech, which included these words: “Old soldiers never die, they just fade away.” Eighteen years later, Rex died as a young soldier in the Republic of Vietnam on Nov. 19, 1969, while serving as an assistant team leader with the 75th Ranger Regiment (Airborne, Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol).

Rex was a happy, healthy boy who had blonde curly hair and sparkling blue eyes. He was a good kid who loved to play soldier and build forts. When he reached school age, he recruited his little brother, who was 2 1/2 years younger, to be his “point man.” His job was to warn Rex when Mom was coming so they could stop jumping on the bunk beds—which were draped in blankets and sheets and had become “The Fort.”

Rex was always a leader who was loved and respected by his peers and especially by his little brother, Dana. They were inseparable.

On New Years Eve 1962, Rex and Dana were sledding in a park in Pennsylvania. Dana was involved in an accident that pinned his leg between the runners of the sled and a tree. He was seriously injured. Rex instructed a friend to get a blanket and call an ambulance. Then he called me at work to tell me what happened. When I arrived, Rex had taken care of everything. He was not even 11 years old.

Rex always wanted a car. In 1967, he bought the shell of an old Chevy with no engine for $100, which he had saved from a part-time job. He was 16 and had the dream of putting a hot engine in that car someday. He even bought a new racing steering wheel for it, made out of stainless steel and wood. He would go out and sit in that old car after school and sometimes at night with his transistor radio—just sit in the car and dream about the day he would get it running. He enlisted in the Army at age 17 and never owned a real vehicle or had a driver’s license.

Rex loved music, played guitar and sang. He was in a small band and sang in the school choir.

We were an Army family. His father, Sgt. Lawrence R. Sherman, had a career that took us many places. Rex started his schooling with kindergarten in Germany, then first grade in Alexandria, Virginia. He went to school in Ohio, West Virginia, Colorado, Kentucky and Pennsylvania. Rex was an average student who opted to serve the country he loved rather than continue his education.

Rex was the ideal son, brother and friend. He was loyal, generous and very patriotic. He had impeccable manners and was very handsome. The girls loved him because of those special traits.

Rex is missed by family and friends every day.

REX MARCEL SHERMAN is honored on Panel 16W, Row 96 of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. He can be visited at Arlington National Cemetery, Section 36-1313.

WILLIAM EDWARD CORDERO

“Santa Barbara’s Almost-Mayor” by Tony Cordero

Years before the United States of America was born, Bill Cordero’s Spanish explorer ancestors arrived in what is now central California. The Corderos were one of the original “land grant” families, receiving thousands of acres from the Mexican and Spanish authorities that controlled California prior to its 1850 statehood. By helping construct the iconic California missions, along with their ranching and farming, Mariano, Juan, Adolpho and other early generation Corderos left their fingerprints on Old California.

Bill Cordero was born in Santa Barbara in 1935, a rustic time between the Great Depression and World War II. In their youth, Bill and his sister Dorothy moved to San Pedro, Calif., for a brief time while their father’s iron work experience took him to the wartime shipyards of the Port of Los Angeles. After the war, the family returned to Santa Barbara, and Bill grew to become a Boy Scout, an altar boy and a high school football player. His father’s eighth-grade education and work as a blacksmith made Bill yearn for more. He dreamed of being the first of his extended family—seven generations of Californios, many without high school educations—to attend college.

When he was accepted into the Air Force ROTC program at Loyola University in Los Angeles, Bill’s life plans were on track. He thought, “I’ll graduate from college, obtain my officer’s commission and climb the ladder in the U.S. Air Force. After 20 years, I’ll retire and return home to become mayor of Santa Barbara.” Back then, the seaside community featured an ethnic mix of blue-collar workers and growing middle-class families.

By that calendar, Bill’s first run for political office would take place in the late 1970s or early 1980s.

Little did he know that a very different campaign involving his name—and 58,000 others—would be waged in that time frame instead: on Veterans Day 1982, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial would be dedicated to the memories of the more than 58,000 service personnel who gave their lives in the Vietnam War. The war that had divided America for so long would be memorialized on the National Mall, listing the name of every serviceman—and eight service women—in the chronological order that they were taken from us.

But, that was decades in the future. In 1957, Bill married a young Irish girl from Los Angeles, and they quickly began their Hispanic-Irish-Catholic family. They welcomed a daughter and three sons before the 28-year-old Air Force officer left for his first combat tour of Vietnam.

Bill arrived at the Bien Hoa Airbase outside Saigon on the day that President John F. Kennedy was killed in Dallas. As an Air Force navigator, he was among the Air Commandos who served as early advisors to the military forces of the Republic of South Vietnam. Viewing old photos of the Air Commandos alongside their B-26 bombers gives the impression of a scene from World War II, not the early 1960s in Vietnam. They were living on a jungle air strip, 8,000 miles from home, flying ancient planes that were literally falling apart on them. The conditions then would hardly pass for “modern warfare.”

After one tour in Vietnam, Bill’s plans were on track. He was credited with combat flying hours, had received commendations for his work, wrote love letters to his wife and inquired about life back in Santa Barbara. “How was the fishing? What’s up with the old gang? How was the Old Spanish Days Fiesta?” A growing war in Southeast Asia was on his mind, but his family and Santa Barbara were in his heart.

Santa Barbara, which today is a hideaway for the rich and famous, was originally a town filled with white stucco buildings and red-brick roofs, populated by hard-working people who took pride in their heritage and their community. Bill wanted to balance Santa Barbara’s need for progress with respect and honor for its past.

In August 1964, Bill’s wife and kids joined him at Clark Air Force Base in the Philippines. Life on the Pacific island was a challenge: weather, food, cinder-block houses, intermittent running water all made for a unique adventure for the family. But they were together, and that was more important than any of the minor inconveniences. For nearly a year, the family traded road trips throughout the Philippines with two-week intervals when Bill would navigate a two-passenger B-57 to Saigon for bombing missions over North Vietnam. As he looked down on the hostile terrain over Vietnam, it appeared vastly different from the views he saw from the cockpit when he was stationed at Oxnard Air Force Base in California and would fly over his boyhood home in the sleepy Santa Barbara hamlet. “The beaches here in Vietnam are the most beautiful I have ever seen,” he once wrote.

In June 1965, Bill celebrated an early Father’s Day—he and his wife Kay were now expecting their fifth child—and departed for another series of bombing missions in Vietnam. In the dark, early hours of June 22, 1965, Bill and his pilot Charles Lovelace disappeared in their B-57 while flying over the border of North Vietnam and Laos. Four years later, the wreckage was discovered just inside Laos, in the province of Bolikhamxai. Despite the mystery of exactly what happened, the nation had lost two warriors; two families had lost their husband and father; and Santa Barbara had lost its future mayor.

Today, Bill Cordero and Charles Lovelace are buried together at Arlington National Cemetery, very close to the Tomb of the Unknowns.

On the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the names of William E. Cordero and his pilot are inscribed near the top of the second panel, beyond the reach of visitors and tourists, and just high enough to catch the glare of the daytime sun.

WILLIAM EDWARD CORDERO is honored on Panel 2E, Row 15 of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

EARL WATSON THARP JR.

“His Great Love” by Jane (Tharp) Woodruff

Earl Watson Tharp Jr. was born on Oct. 3, 1949 to Earl and Billie Tharp. Nineteen months later, on May 17, 1951, Stephen Wayne Tharp was born. I was the last child, born September 20, 1958.

Earl got the baby sister he wanted when I was born. Even though there were nine years between us, we had a bond that defied our age difference. He faithfully loved me and made me feel wanted. I always knew I was special to him. Likewise, he was very special to me. I thought he was great—strong, handsome, generous, patient and kind. I felt safe and secure with him.

Earl was a natural mechanic. In his pre-teen years, without my parents’ knowledge, he took apart a Victrola and put it back together. In his teen years, he was an avid motorcycle rider. He was eager to work in high school to save up money for his own car. He could do most of his own repairs on both vehicles.

Earl and I had great fun going on motorcycle rides. He would take me to the Martha Washington Ice Cream Parlor for a treat, just the thing for his 10-year-old sister.

Earl was strong. One of my fond memories is of him challenging me to hit him in the stomach as hard as I could. When I did, I felt like I was hitting a wall. I was so impressed with his strength.

Earl was handsome, and the girls knew it! He would always make sure that his girlfriends treated me well. I think some of them thought I was part of the package and treated me like a little sister.

Earl was generous. While he was in Vietnam, he sent me, his 11-year-old sister who was broke, money to buy Christmas presents. The last letter he sent me, which arrived after his death, included $40 for me to spend however I wished. To me that was a fortune—and a final demonstration of his selflessness.

Earl was patient. I remember when I was five years old, he spent hours with me while I was learning to ride a bicycle, running behind to keep it balanced.

Earl was respectful of authority. He was offended by attitudes and acts of those who participated in anti-war protests. While in Vietnam, he became disillusioned with how our leaders were handling the war, but he maintained a respectful attitude.

My brother was kind. He faithfully wrote letters, always eager to hear news from home. He sent Christmas cards to friends, some of whom were elderly. He and my brother Steve were particularly close. They played together, worked together and were the best of friends. Earl loved hearing all the latest news from Steve, be it college studies, car repairs or finances. When Earl died, Steve not only lost his big brother, but he also lost his best friend.

When Earl graduated from high school, he promptly enlisted in the Army and served with Company B, 229th Aviation Battalion (Assault Helicopter) (Airmobile). He wanted the people of Vietnam to have the freedom we had. He wanted the children of Vietnam to have a better life than their parents.

He was only in Vietnam for a few days before he began counting the days until he would be home.

Given his mechanical skills, it was no surprise to find out that he would be a helicopter gunner, and, subsequently, crew chief overseeing maintenance of a helicopter. He took his job very seriously, knowing that a faulty engine could cause the deaths of his comrades.

Earl’s fellow soldiers gave him the nickname “Preacher” because of the example he set and his faith in Jesus. My brother expanded his capacity for love while in Vietnam. On June 26, 1970, he demonstrated this with honor when his base came under heavy rocket and mortar attack.

Earl made it to the protection of a sandbagged bunker. But when he saw that a friend caught in the open fire had been seriously injured and was unable to get to cover under his own power, Earl ran through a barrage of exploding rounds to help. Before he could carry his wounded friend to safety, an exploding round mortally wounded him. He died a short time later.

In the Bible, John 15:13 says: “Greater love has no man than this, that he lay down his life for his friends.”

My brother died carrying a friend, not firing a gun. He laid down his life for a friend he knew less than two years.

He is a hero. I honor him for his great love.

EARL WATSON THARP JR.is honored on Panel 9W, Row 97 of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

ROBERT WILLIAM CUPP

“Bob Cupp: A Son and Brother” by Emogene Cupp and Sue Rampey

Cpl. Robert William Cupp, son of James Russell Cupp and Emogene Moore Cupp, was born June 17, 1947 in Alexandria, Virginia.

Bob attended Bush Hill Elementary School, Mark Twain Middle School and Edison High School. He loved baseball and would throw the ball against our brick house and catch it. There were two large picture windows on the second floor of the house. He must have pitched that baseball thousands of times against the house between those windows and never broke a window! Every year that he was eligible, he played Little League Baseball and was fortunate enough always to be on the winning team.

He was drafted into the Army on August 24, 1967, and after receiving his basic training and his advanced training, he was shipped to Ft. Lewis, Washington for deployment to Vietnam.

Bob’s leave at Christmastime 1967 was a surprise to his family. We were so happy to see him, not realizing that it would be our last Christmas together.

We took him to Dulles Airport in February 1968 for his flight to Ft. Lewis, Washington, and from there, he went on to Vietnam. Paul Copeland, an Army buddy he had gone all through training with, said he and Bob sat side by side on the flight to Vietnam. When the two arrived, they were put in different units. When their units crossed paths again, Paul learned that Bob lost his life when he stepped on a land mine.

There is no other feeling like opening your door to a knock and there stands a military man; you know it is bad news. He told us that Bob had been killed instantly on June 6, 1968 when he stepped on a land mine. The funeral was held on his 21st birthday.

Bob’s friend from their school days, Steve Davenport, has always kept Bob in his heart. He sent roses to Bob’s funeral, remembering the pact the two made: that whoever died first, the other would send roses. Steve also made one of Mrs. Cupp’s favorite possessions. It is a beautiful 25” x 25” black lacquer display box containing the medals Bob earned, his picture and his name etched in the glass from a rubbing on The Wall. He made a duplicate and placed it at The Wall, and it is now in the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Collection of items that have been left at The Wall.

Bob’s mother was pleased to be able to go to Vietnam in August 2002 and see where Bob was killed. Thanks to the veterans of the Dusters, Quads & Searchlight Organization for making the trip possible. Bob and Susan Lauver, Mike Sweeney and Greg Dearborn were great caring individuals to accompany the mothers and have so much compassion for them. Vietnam is a beautiful country just like Bob said in his letters.

Jim, Bob’s father, died on June 26, 1990. His parents, with scars on their hearts, will always remember their loving son, Robert William Cupp.

ROBERT WILLIAM CUPP is honored on Panel 60W, Row 27 of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

JAMES ALBERT BUNN

“A True Soldier” by Rachel Bunn Clinkscale

All of his life, my husband James A. Bunn wanted to be a soldier. His Uncle Howard Royal died while serving in World War II, and he was Jim’s hero.

Even when he was a little boy, Jim was a leader and a protector. I recall when he was six and I was five, we were playing in the park with some other children, one of whom stepped on a piece of glass and was bleeding. Jim picked her up and ran several blocks home with her to get help.

When Jim was 17, his mother signed for him to enter the Army. He served in Korea near the end of the conflict. When he came home, we were married.

He said to me, “If there is ever a war, I’ll be one of the first to volunteer to go.”

He served his first tour in Vietnam with the 101st Airborne from 1965-1966. After he came home, we were stationed at Ft. Campbell, Ky., where he was an instructor at the airborne jump school. He had been back less than a year when he came home and said the 3/506 was being reactivated, and he was going with them. He thought his experience might help to keep some of the young soldiers alive that were being sent to Vietnam. Jim died Feb. 2, 1968, trying to rescue one of those young soldiers.

Years later, I heard from several of those young men who described what happened and how Jim died. Jim was the platoon sergeant for Company A of the 3/506 and following are some of the comments made by those who served with him:

“Platoon Sgt. James Bunn has rarely ever been far from my mind. He was a good man and brave, and all of those things that we admire about exceptionally honorable people. I never worried about anything because I knew Jim Bunn had my back covered, and he did.”

—Lt. John Harrison

“Vaughn [DeWaay] was there when Jim was hit and returned to bring him out. He loved Jim so much, he was the one person he would talk about. He called Jim his ‘father figure’ and said there wasn’t a time that Jim wouldn’t sit and listen when he needed to talk to someone.”

—Catherine DeWaay, wife of Vaugh DeWaay

“Platoon Sgt. Bunn was our mentor and hero. His men respected him very much and would follow him ‘to hell and back.’”

—Jerry Berry

“The day after Jim was KIA [killed in action], I helped evacuate him on the chopper, at which time I put my hand on him and gave him my ‘Aloha.’ Throughout all these years, I have thought about that day. As platoon sergeants, we tried to watch over the men as much as possible. Jim was much more experienced and made me feel confident that I also would do a good job. I feel I owe him a great deal.”

—Joe Jerviss (Pineapple)

My husband was a true soldier who died for what he believed in. Not many of us can say that or be remembered this way. All of the names on The Wall represent individuals who were and are our true heroes.

JAMES ALBERT BUNN is honored on Panel 36E, Row 66 of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.