Thank you to the following reviewers of the curriculum: Andrew Demko, Rainier Junior/Senior High School; George Herring, University of Kentucky; Mark Lawrence, University of Texas at Austin; Susan Tomlinson, Franklin Central High School.

Teachers/Presenters:

Download Presentation – does not require internet connection

ABOUT SOCIAL MAKEUP OF FORCES

Who do you think should serve in the military? Do you think there should be efforts to make the military a reflection of society in its makeup? Why or why not?

During the Korean War, 70% of draft-age men served in the military. During the Vietnam War, that figure dropped to 40%, with only 10% of draft-age men serving in Vietnam—making military service a less universal experience and setting those who did serve farther apart from society at large. The US soldiers who fought in the Vietnam War were different in many ways from those who had fought in earlier wars. The average age of a soldier in Vietnam was 19, and he was likely to be unmarried—a significant difference from, for example, the average age of 26 for a soldier in World War II (see slide 1, a group of young soldiers including Jan Scruggs, the founder of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.) The youth of the average soldier was in many ways related to the draft and the system of deferments for the draft—enrolling and staying in college became an incentive to many, as college enrollment was an allowed deferment. For those who could not afford to enroll in college, there were few ways to avoid the draft. Overall, 25% of those who served in Vietnam were draftees.

Partly as a consequence of the system of deferments, the Vietnam War was largely fought by men from working class backgrounds—76% of soldiers in Vietnam came from working or lower class backgrounds. This has led many to characterize Vietnam as a “working-class war,” which served as a reason for some to demonstrate against the “rich man’s war” (see slide 2). Some of those soldiers, and many within the working class subset, were racial minorities. Slide 3 shows Melvin Morris, a Congressional Medal of Honor recipient who was awarded the distinction for leading an advance across enemy lines to recover the body of a fallen sergeant. African Americans made up about 10 % of all US soldiers in Vietnam, reflecting their numbers in the broader American population. However, African-Americans comprised about 20% of combat deaths in the early years of the war because they tended to be assigned to front-line infantry units.

The youth of American servicemen in Vietnam prompted a civic debate on whether it was appropriate to send a person to war who could not vote for representatives making decisions about war and peace. The voting age in the Vietnam era was 21 years old. Observe closely the poster included on slide 4, which seeks support for the lowering of the voting age. Do you agree with the Lincoln quote? Why or why not? How could someone make a case against the lowering of the voting age? In March 1971, the 26th Amendment was passed, making 18 the official voting age across America for federal elections. The voting age for state and local elections is determined by state and municipalities—some areas will allow those as young as 16 to vote in elections. What do you think an appropriate voting age would be? Why?

Compare the heat maps on slides 5 and 6, which compare the states of origin for casualties from Vietnam to casualties from Afghanistan and Iraq. Do you see any significant differences? What kind of conclusions can you make by comparing the two maps? In terms of casualties, the geographic distribution is largely unchanged: the greatest number of casualties come from the most populous states. However, in terms of total service, since the end of the draft in 1973, the makeup of the military has shifted south—percentages of service men and women from the Northeast and Midwest have dropped, while percentages from the West and South have risen. In 2000, 42% of all recruits came from the South. Observe the map of veteran populations on slide 7. What conclusions can you draw from this map? Do you think these maps give useful information about whether today’s military is representative of American society as a whole?

Regardless of the various backgrounds and circumstances that soldiers come from, it is important to recognize their service to the nation.

Thank you to the following reviewers of the curriculum: Andrew Demko, Rainier Junior/Senior High School; George Herring, University of Kentucky; Mark Lawrence, University of Texas at Austin; Susan Tomlinson, Franklin Central High School.

Teachers/Presenters:

Download Presentation – does not require internet connection

ABOUT MEDICAL ADVANCES IN VIETNAM

What are some of the positive impacts of war? It may be hard to identify many, but all can agree that the advancement of medicine and medical care are positive consequences of the challenges faced in war.

During World War II, combat medics, or military personnel whose primary duty is to provide frontline trauma care, provided the first step of care to an injured solider at aid stations on the field, as depicted in slide 1. For those that needed further care, ground evacuations by ambulance, such as the one depicted in slide 2, brought soldiers to mobile field hospitals if present in the area. Slide 3 depicts a field hospital in Bougainville, New Guinea during WWII, where necessary procedures like amputations might have been performed to treat traumatic injuries. Over 15,000 soldiers received amputations of limbs in World War II as a result of their injuries.

During the Korean War, the installation of Mobile Army Surgical Hospitals (MASH), which were first introduced in World War II, became the standard for treating extensive traumatic combat injuries. Injured soldiers would first be taken to aid stations and then routed to MASH facilities, such as the ones depicted in slides 4 and 5. As a result of the wide presence of MASH facilities, the mortality rate for those evacuated from the field dropped from 4% in World War II to 2.5% in Korea, meaning a wounded soldier who was evacuated had over a 97% chance of surviving.

Another major medical advance of the Korean War was the improvement in vascular reconstruction surgery, or the repair of arteries and vessels. Improvement in vascular reconstruction led to a significantly lower rate of amputation as compared with World War II, at just 13% of the injured vs. 36% in World War II. Famed Army surgeon Michael DeBakey (seen in slide 6) was a pioneer in both the widespread establishment of MASH facilities and the improved methods for vascular reconstruction. Further improvements in vascular reconstruction reduced the amputation rate in Vietnam to just 8%.

With the Vietnam War came major advances in medical care, some of which continue to be used as standard practice in civilian medical care today. Perhaps the most significant innovation in medical care of the Vietnam War was the widespread use of air ambulances for helicopter evacuation—also known as medevacs (see slide 7). The Bell UH-1 helicopter reduced the amount of time from wounding to treatment to an average of 35 minutes, a monumental decrease as compared to the 4-6 hours from wounding to treatment for the evacuated in Korea (see slide 8). There were a total of 116 helicopter ambulances operating in Vietnam by 1968, and after state authorities in the US began following suit in using helicopters to transport highway crash victims, the practice became the norm—many hospitals in the US have helicopter landing pads for this purpose.

Another innovation which factored into a greater ability to receive medical care was the installation of long-range radios able to cover distances of up to 5 miles- they were known as PRC-25s, as seen in slide 9. The widespread use of long-range radios reduced the response time to an injured solider—it took an average of just 9 minutes from request to the launch of a medevac toward its destination. Improved radio communication also meant that the status and needs of the injured solider could be relayed to the hospital while en route. “Dust-off” became the radio signal to call for air evacuation (see slide 10). Dust-off continues to be the term used to refer to air evacuation crews.

Perhaps the greatest innovation in medical care introduced on a wide scale in Vietnam was the use of pre-hospital care by para-medical professionals, a system which is now known to the public as EMS (Emergency Medical System). The para-medics that administered care before a wounded solider could be transported to a hospital would perform certain procedures such as shock resuscitation and fluid replacement, with a more organized blood program to more quickly assist those suffering from major blood loss. The use of non-type specific blood (O negative, which is the universal donor) was introduced on a wide scale in Vietnam and has become the standard practice in blood transfusion for traumatic injuries.

Since Vietnam, medical care has continued to evolve as result of challenges faced on the battlefield. In 1995, damage control surgery was introduced and has since become the standard procedure for care in settings like Iraq and Afghanistan. The goal of damage control surgery is to perform stabilizing surgery before an injured solider is able to reach intensive care, doing only what’s needed to prevent ongoing blood loss and organ spillage (see slide 12). Soldiers serving in Iraq and Afghanistan have also have benefitted from medical innovations such as chitosan or Quik-Clot, which are derived from the shells of shrimp and speed up the process of clotting when applied to a wound, to prevent major blood loss (see slide 13).

Innovations in the transportation of the injured have also impacted the level and immediacy of care for wounded soldiers. The use of medevacs in Vietnam was revolutionary in the 1960’s; the use of “Flying ICUs” is considered a remarkable advance in the context of today’s military conflicts. Flying ICUs (intensive care units), as seen in slide 14, are Air Force planes which have permanently installed ICU devices and a range of skilled medical professionals able to provide the highest level of care within minutes of wounding. While many advancements in medical care were introduced at a wide scale in Vietnam, military medical care continues to advance today and influence medical care in your own local hospitals. In looking at the level of trauma that soldiers often must go through, it is important to recognize their service to the nation.

From the Veterans History Project, Larry Schwab collection: Army medic Larry Schwab discusses the impact of medical evacuation by helicopter in Vietnam.

Thank you to the following reviewers of the curriculum: Andrew Demko, Rainier Junior/Senior High School; Mark Lawrence, University of Texas at Austin; Susan Tomlinson, Franklin Central High School.

Teachers/Presenters:

Download Presentation – requires internet connection

Download Presentation – does not require internet connection

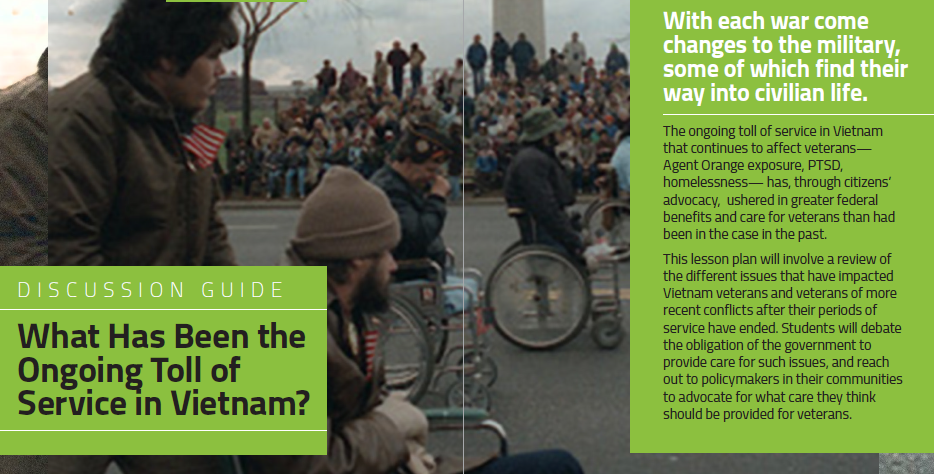

ABOUT THE ONGOING TOLL ON VETERANS

What obligation do you think the government has to its veterans after their period of service has ended? Why? Though individual periods of deployment may be short, the effects of service may stay with veterans for the rest of their lives.

Perhaps the most publicized cause of ongoing health issues in Vietnam veterans is exposure to Agent Orange, which resulted in myriad diseases and birth defects that are carried forward in the children of those exposed. Agent Orange was a chemical compound developed by Dow Chemical to serve as a defoliant—meaning it would kill crops and other vegetation in the areas where sprayed (see slide 1)—that would aid in rapidly and effectively clearing areas of the Vietnamese countryside that might provide cover to enemy troops and feed the people. In spite of some initial research that suggested the use of the chemical compound could create health problems for those exposed, the defoliant was used widely in Vietnam. Those who were exposed to Agent Orange may end up developing a range of health problems, including Parkinson’s disease, Hodgkin’s disease, prostate cancer, respiratory cancer, and more. In 1979, President Jimmy Carter authorized the first Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) study of Agent Orange, to evaluate the effects of the chemical compound on the pilots who sprayed it. After a decade of lawsuits filed by veterans for compensation to cover medical treatment needed as a result of Agent Orange exposure, the Agent Orange Act was established in 1991 to allow the VA to declare a range of diseases as probable effects of Agent Orange exposure, and thus veterans could pursue services in relation to those diseases.

Watch the news report included on slide 2, which features veterans speaking to the long-term effects of their exposure to Agent Orange. What additional effects does Agent Orange exposure have, beyond the diseases and cancers that directly impact veterans? Do you think the government has an obligation to provide compensation for the children of Vietnam veterans who may suffer medical problems that are passed along genetically? Why or why not? Do you think a defoliant such as Agent Orange is a legitimate weapon to use in war? In addition to affecting the children of Vietnam veterans, Agent Orange exposure has had widespread effects on generations of Vietnamese, both those living on land that still contains Agent Orange, and those who are children of people originally exposed during the war (see slides 3 and 4). Many Vietnamese children have been born with irreversible birth defects that can be traced to Agent Orange. What obligation does the United States have to help these people?

There are other effects of service that continue when veterans have returned home. Some veterans may have trouble finding work due to physical or mental health problems, which can ultimately lead some to become homeless. Look at the infographic on slide 5, which shows the number of homeless veterans in each state. How many homeless veterans are there in your state? What percentage of the national total does your state represent? What message does the political cartoon on slide 6 send? War impacts nearly all veterans, even some of those who return home.

In addition to possible health problems resulting from Agent Orange exposure, some Vietnam veterans, as well as veterans of other wars, suffer from post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD). In 1970 Dr. James Lifton, a famous psychiatrist at the time, first testified to Congress about the effects of “Post-Vietnam Syndrome,” a condition he was seeing among patients who were veterans of the war. Eventually this syndrome as coined by Lifton came to be known as PTSD. Look at the image on slide 7, which shows an item from the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Collection (http://www.vvmf.org/items/). What obstacles do you think PTSD might create for a veteran looking to return to civilian life? What obligation do you think the government has to respond to veterans with PTSD? Ask students to observe the chart on slide 8, which shows the rise in PTSD. What does the chart tell us about PTSD across different eras of service? The National Center for PTSD estimates that 30% of Vietnam veterans have PTSD, and 10-20% of veterans of more recent wars suffer from PTSD.

Some health consequences faced by veterans are specific to the wars in which they served. For veterans of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, exposure to chemical smoke at burn pits (as seen on slide 9)—a military practice to dispose of waste—is starting to take its toll on veterans’ health. The Department of Veterans Affairs has stated that studies on the health impacts of exposure to the chemical smoke of burn pits are currently limited. This means that veterans suffering from related health problems, like reduced lung function, cannot receive the full funding they may need to cover their medical care.

In particular because the effects of service do not end when a soldier returns home, it is important to recognize veterans’ service to the nation.