Thank you to the following reviewers of the curriculum: Andrew Demko, Rainier Junior/Senior High School; George Herring, University of Kentucky; Mark Lawrence, University of Texas at Austin; Ed Moise, Clemson University; Susan Tomlinson, Franklin Central High School.

Teachers/Presenters:

Download Presentation – requires internet connection

Download Presentation – does not require internet connection

NEWS STORIES OF VIETNAM

What types of information do you think news outlets have a responsibility to report to the public? Why?

In large part, particularly in the early years of the Vietnam War, news reports focused on major military developments as the war progressed, such as the March 1965 New York Times article featured on slide 1 that details the deployment of Marines to Da Nang. In late 1966 and early 1967, Harrison Salisbury of The New York Times was the first reporter from a major news publication who travelled to North Vietnam to capture in-depth reports. The result was a series on the damage of US bombing to civilian areas in North Vietnam. Read aloud the excerpt of Salisbury’s article included on slide 2. Would you interpret the language of the headline and lede as being critical of the war or any particular group? Why or why not? Is the tone of the story fair and appropriate to the topics under discussion?

January – February 1968 marked the Tet Offensive, a series of attacks by North Vietnam and the National Liberation Front (NLF) in South Vietnam. With this major blow, which involved heavy US casualties, came a shift in attention of major news outlets toward a perspective alternate to the standard information shared by the Department of Defense. For example, the 1968 article from the Chicago Tribune included on slide 3 features the headlines “South Vietnamese Caught Napping,” implies that perhaps America’s ally was not as prepared as official views might state. The article, however, is quick to deflect blame from American troops—“Despite warnings from the United States military command that large scale attacks were imminent.” Read the article excerpt: Would you interpret the article as (overall) being critical of the war or any particular group(s)? Why or why not? Is the tone fair and appropriate to the subject?

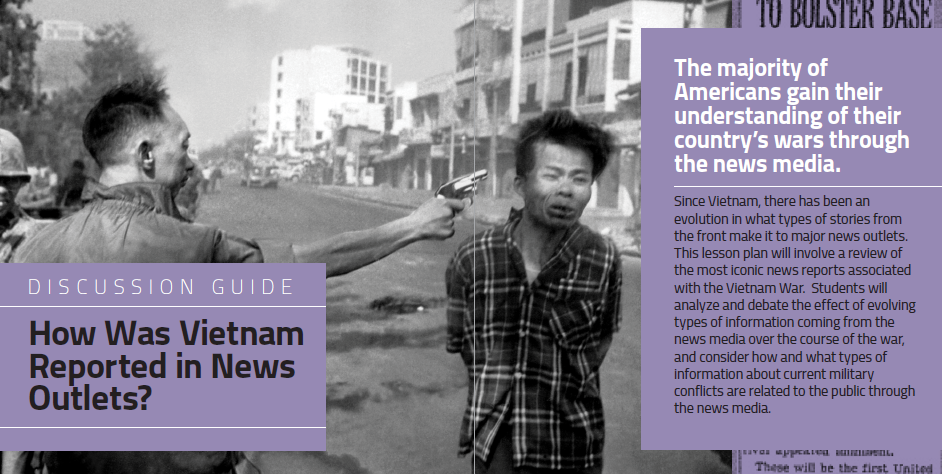

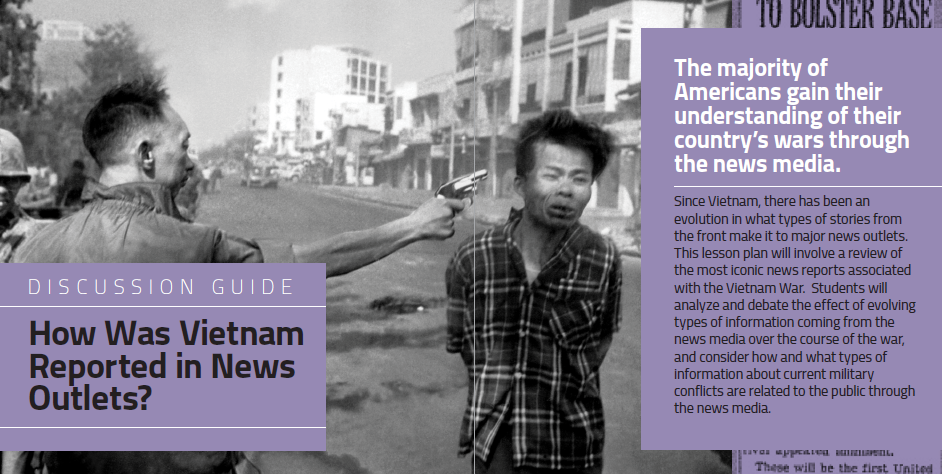

Former Marine Eddie Adams served as a photographer for the Associated Press in Vietnam and took the now iconic photo on slide 4 of South Vietnamese police chief General Nguyen Ngoc Loan killing NLF/Viet Cong suspect Nguyen Van Lem in Saigon in 1968 in the wake of the Tet Offensive. The image appeared in The New York Times, and through it American citizens were able to see the brutality of war, perhaps forming a new view of South Vietnam.

As the public’s discontent with the war grew, so did opportunities to report on public criticism of the war, largely expressed through demonstrations. The November 1969 Los Angeles Times article included on slide 5 showcases the growth in news reports on the war that focused on topics outside of military developments as relayed by officials—like public opposition in response to President Nixon’s address to the nation on the war (text of speech: http://www.nixonlibrary.gov/forkids/speechesforkids/silentmajority/silentmajority_transcript.pdf). Similarly, on slide 6 is a Chicago Tribune report of a well-publicized demonstration organized by Vietnam Veterans Against the War in 1971, in which veterans returned their service medals at the steps of the Capitol.

One news story which similarly gave a new perspective to the progress of the war was the reporting of the 1968 My Lai massacre, which was the mass killing of South Vietnamese civilians by US Army soldiers. The image on slide 7, taken by US Army photographer Ronald Haeberle, shows some of the civilian casualties of the My Lai massacre. This iconic image, which was first published in 1969 in The Plain Dealer, a newspaper based in Cleveland, Ohio, has come to be among those most associated with the war. The photos published in The Plain Dealer were eventually used as key evidence by the US Army to investigate the incident.

In 1969, President Nixon authorized strikes against Cambodia, directed at locations that were believed to be strongholds of North Vietnam. These strikes were not authorized by Congress, leading critics to charge that the strikes were illegal under U.S. law. News of the secret strikes were first reported by correspondent William Beecher, whose breaking story is featured on slide 8. Read the text of the article included on the slide. Would you characterize the information given and language used as providing a fair perspective? Why or why not?

Later on in the course of the war, the landmark story that would come to represent a new era of reporting was the release of the Pentagon Papers, a study commissioned by the Pentagon to examine the origins of US involvement in Vietnam. The Pentagon Papers were not intended to be shared with the public, in part because many of its conclusions suggested that the war’s escalation and continuation were questioned by many leaders, sometimes in spite of public language to the contrary. Do you think the Pentagon Papers, which came to the attention of the New York Times through an illegal leak by a disgruntled official (see slide 9), should or should not have been released for public knowledge through the news media? Why or why not? Why do you think the Supreme Court ruled that the New York Times and, later, the Washington Post were allowed to publish this material?

The news stories of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan in many ways followed in the footsteps of Vietnam, with coverage of both major military milestones as well as reporting on incidents of misconduct by the military. Because of a perception that media reporting had become too negative and undercut support for the war in Vietnam, greater control over reporting was exercised by the military in later conflicts. When the US invaded Iraq in 2003, reporters were embedded within the military, living with soldiers and sometimes going on missions. The public now had an expectation of frontline coverage, and the military’s system of embedded reporting provided to journalists that frontline coverage. Many journalists, however, saw the reports of embedded journalists as providing only a microscopic and tightly managed view of reality. For example, during the first two weeks of the invasion of Iraq, three out of four sources quoted in news reports were military officials, and military successes were emphasized.

Among the major stories of the war in Iraq were the invasion of Baghdad in 2003 (slide 10) and the capture of Saddam Hussein (slide 11). In slide 11, you see an iconic image of Operation Red Dawn, in which former Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein was captured by US forces. This image became particularly iconic because the man seen in it was an Iraqi civilian translator working with US forces. This image was taken with the translator’s own phone and he has been able to speak to this moment in the conflict and share with media outlets without the prior intervention of the military in telling this story. The translator has suggested that the release of the photo raised the ire of top-level military officials.

Perhaps the most noteworthy news stories to emerge out of the Iraq war were reports on cases of torture and abuse at the Abu Ghraib prison run by US-led forces in Iraq. Watch the 2004 news report on Abu Ghraib prison torture and investigation included on slide 12. What is your reaction to this incident? Would you characterize the information given and language used as providing a balanced perspective? Why or why not? Is the tone of the reporting fair to the subject at hand?

The US government exercises far more control over reporting on military operations in the twenty-first century than it did half a century ago in Vietnam. This has impacted the way that wars are reported, and reminds us all of our civic responsibility to remain informed about what is happening on both a national and international level.

Gen. Peter Pace discusses a free press.

Thank you to the following reviewers of the curriculum: Andrew Demko, Rainier Junior/Senior High School; George Herring, University of Kentucky; Mark Lawrence, University of Texas at Austin; Susan Tomlinson, Franklin Central High School.

Teachers/Presenters:

Download Presentation – requires internet connection

Download Presentation – does not require internet connection

ABOUT WAR ON THE HOMEFRONT

What is the role of media in society: Is it to keep citizens informed? Is it to tell the truth at any cost? Is it to influence change? Is it to confirm what we already believe? Can the media play several roles at once?

Across much of American history, the U.S. government exercised little control over the ability of the news media to report on military operations. But during the First and Second World Wars, the United States placed new restrictions on the flow of information. During the Second World War, for example, the newly established Office of Censorship circulated a “Code of Wartime Practices for the American Press,” which prohibited journalists from reporting any information – everything from details about troop movements to weather reports to industrial production figures – that might have value to the enemy.

The government also established the Office of War Information (OWI), which produced propaganda aimed at bolstering morale on the home front, encouraging Americans to accept sacrifices, and shaping the way Americans understood the motives underlying the nation’s war effort. The OWI was probably most famous for its newsreels (which would accompany feature films) but also produced posters, advertisements, brochures, and books. View 2-3 minutes of the newsreel included in the presentation. Discuss with students: What is the tone of the newsreel? What is the message you would take away from this newsreel regarding this particular battle? How were the images and video for the newsreel obtained?

View a 2-3 minute selection of the Why Vietnam? program – a piece of government propaganda similar to the newsreels produced during the Second World War — included on slide 2 of the presentation. This film outlines for the American public US policy in Vietnam, with statements from President Lyndon Johnson and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. Although independent media covered the war intensely (especially after 1964), such government-produced material may have helped generate strong popular support for the war in its early months. As time passed, however, independent media, including the major television networks and newspapers such as The New York Times and Washington Post, presented a more accurate and balanced view of the war. Critics charged that the news media went too far, casting too negative a view of the war and straying too far from the outlook of senior government officials. But one reason for the media’s sometimes-critical view of the war, especially after 1968, was the government’s dwindling credibility. Daily press briefings given by the U.S. military command in Saigon were referred to by reporters as the “Five O’Clock Follies,” as the information given was often limited, trivial, or even misleading.

Americans also learned about the Vietnam War from photographs, including some of the most iconic war images in American history, taken by photographers for the New York Times, the Associated Press, and other major news media organizations. Examine the series of photos included as slides 3-6 in the presentation. In the first, former Marine Eddie Adams served as a photographer for the Associated Press in Vietnam and took this now iconic photo of South Vietnamese police chief General Nguyen Ngoc Loan killing Viet Cong suspect Nguyen Van Lem in Saigon in 1968. The image appeared in The New York Times, and American citizens were able to see the brutality of war, and perhaps in some cases formed a new view of South Vietnam.

Following is another iconic image, taken by LIFE magazine’s Larry Burrows, of wounded Marine Gunnery Sgt. Jeremiah Purdie, center, reaching toward a stricken soldier after a firefight south of the Demilitarized Zone in Vietnam in 1966. The standard practice among the news media was not to publish graphic images of the wounded or dead, and the “reality” of this image meant that it wasn’t published until 1971, five years after it was taken.

The news media had always covered antiwar activities during other periods of American history, but the unprecedented scale of dissent during the Vietnam War meant that the subject received extensive coverage. This iconic image depicts high schooler Mary Ann Vecchio screaming as she kneels over Kent State student Jeffrey Miller’s body during a deadly anti-war demonstration at Kent State University in 1970. Student photographer John Filo captured the Pulitzer Prize-winning image after Ohio National Guardsmen fired into a crowd of protesters, killing four students and wounding nine others. With this image, the costs of war are reported not only on the battlefield but also at home.

Following is a photo of a US solider prominently wearing a peace sign, which might have led the average viewer at home to believe that even the troops who were serving were not fully supportive of the war in Vietnam. Images like this are perhaps evidence of the military’s relatively lax rules during the Vietnam War on journalists’ access to ordinary soldiers.

Americans’ opinions about the war were shaped not just by news reports and photographs but also by editorials. While many media remained supportive of the war, some major news organizations became increasingly critical as time passed. In February 1968, CBS News aired on television a special report on the aftermath of the Tet Offensive. At the end of the report, renowned anchorman Walter Cronkite read a brief editorial suggesting that the United States was mired in a stalemate. Play the video clip from the CBS report included in the presentation. What is Cronkite suggesting as a course of action for the US in Vietnam? It is claimed that after President Johnson watched the report, he said “If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost middle America.” In March of 1968, Johnson announced that he would not seek reelection.

In 1971, the Pentagon Papers were published in The New York Times. This report contained a history of the US role in Indochina from World War II until May 1968, a report which was classified as “top secret” by the federal government. After the third daily installment appeared in the Times, the Department of Justice obtained a temporary restraining order against further publication of the classified material, contending that further publication of the material would cause “immediate and irreparable harm” to national defense interests. But the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Times, allowing the newspaper to go ahead with publishing government secrets. The publication of the Pentagon Papers was a landmark event in the nature of war reporting, with the public being able to read an internal government analysis of the decisions that had led the United States to war in Vietnam.

Following the Vietnam War, the Department of Defense adopted new rules to assure much tighter control over the activities of journalists in war zones. During the Gulf War of 1991, for example, coverage of the war was restricted to reporting pools accompanying carefully selected military units, and pool reporters had to agree to submit their reports to military censors for review. In the presentation, you see an iconic image from the Gulf War in which Sergeant Ken Kozakiewicz weeps as he learns that the body bag next to him contains the body of his friend Andy Alaniz, who had been killed by friendly fire. David C. Turnley of the Detroit Free Press managed to take this photo despite the Pentagon’s ban on taking images of soldiers’ deaths and coffins. Gulf War correspondent Chris Hedges of The New York Times has said “Our success was due in part to the understanding of many soldiers of what the role of a free press is in a democracy. These men and women violated orders in order to allow us to do our job.”

When the US invaded Iraq in 2003, reporters were embedded within the military, living with soldiers and sometimes going on missions. This system meant that reporters could sometimes get close to the front lines and cover spectacular stories, but it also meant that the military exercised tight control over where reporters could go and what they could see. As a result, many journalists saw the reports of embedded journalists as providing only a microscopic, distorted view of reality. During the first two weeks of the invasion of Iraq, three out of four sources quoted in news reports were military officials, and military successes were emphasized. View the video clip included in the presentation of Robert Riggs, an embedded reporter documenting the march on Baghdad. What in the language and imagery of the video might a viewer critique as being controlled or incomplete?

Here you see an iconic image of Operation Red Dawn, in which former Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein was captured by US forces. This image became particularly iconic because the man seen in it was an Iraqi civilian translator working with US forces—this image was taken with the translator’s own phone and he has been able to speak to this moment in the conflict without the prior intervention of the military in telling this story. The translator has suggested that the release of the photo raised the ire of top-level military officials.

To escape the limits of embedded reporting and get a fuller sense of war, some reporters and photographers have attempted to operate on their own, free of the military’s control. In documenting the war in Syria, freelance photographer James Foley was kidnapped in 2012 by unidentified organized forces. In August of 2014, video footage was released of Foley being beheaded as a response to American military intervention against ISIS/Da’esh. Nearly two-thirds of the journalists killed in combat or crossfire in 2014 were freelancers. Why are reporters sometimes driven to take great risks? What kinds of reporting are most likely to provide information of greatest interest and importance to the American public? What is the government’s appropriate responsibility in controlling or shaping information about war?

The US government exercises far more control over reporting on military operations in the twenty-first century than it did half a century ago in Vietnam. This has impacted the way that wars are reported, and reminds us all of our civic responsibility to remain informed about what is happening on both a national and international level.